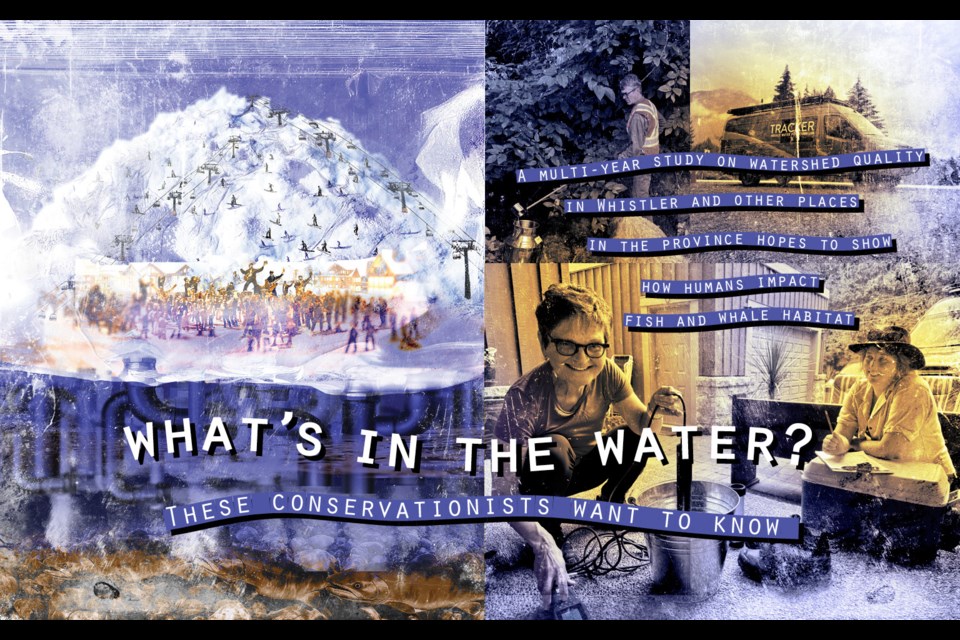

It’s half past 9 a.m. on Aug. 20, and rain clouds roll in over Whistler. Droplets periodically plop on Dr. Peter Ross and a team of conservationists gathered on Lake Placid Road. It’s a fitting scene, given their assignment.

Ross is from the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, a non-profit team of scientists and conservationists. Raincoast uses science-based evidence to understand what impacts coastal species, informing communities and decision-makers and inspiring action to protect wildlife and the places it lives.

An ocean pollution expert, Ross is in Whistler for a project called Healthy Waters, in partnership with the Whistler Lakes Conservation Foundation (WLCF). While the coast doesn’t reach the ski town, water from glaciers, rivers and streams, road run-off, and tap water eventually finds its way into the frothing sea. Healthy Waters aims to show how humans impact each point.

The WLCF advocates for lake stewardship and has partnered with Raincoast on the project in Whistler, because water, whether in rivers, ditches or lakes, is all connected.

“We can’t look at all those elements—ocean, streams and lakes—in isolation; they’re all an integral part of the watershed,” explains Lynn Kriwoken, president of the WLCF.

Ross, a tall and inquisitive man with dark-rimmed glasses, along with Kriwoken and Samantha Scott, water-quality coordinator on the project, grabs a large, stainless-steel container and a testing instrument before walking over to Jordan Creek. They’ve been going at a quick clip since 7 a.m., driving to rivers, ditches and streams, pooling samples to send to laboratories and testing in the field.

At the creek, which links Nita Lake and Alpha Lake, Kriwoken dips a black rod into the water and calls out numbers for oxygen levels, turbidity, pH and more. Ross puts a cup on a long rod into the stream and pours it into the container.

In one day, they’ll sample 15 sites from five categories: source water, stream and river, road run-off, tap water and marine samples.

It’s the third time they’ve done this in the Green River and Cheakamus River watersheds for the project. The Green River watershed drains northeast and connects to the Lillooet and Fraser rivers before reaching the Strait of Georgia—a flow that spans 975 square kilometres. The Cheakamus River watershed drains into the Squamish River before reaching the Howe Sound, covering 1,034 square kilometres. Collectively, it’s 1,909 square km.

The first two preliminary data sets, in the dry season of 2023 and the wet season in 2024, have publicly available reports that show the Green and Cheakamus watersheds are in relatively good shape.

A second report will provide a longer-term look at the health of Whistler’s watersheds, and hopefully reaffirm the initial findings.

“At the end of the two-and-a-half years, we’ll return to our partners—the Resort Municipality of Whistler, Vail Resorts—if there’s any red flags in the data that point to certain sources or pathways,” Kriwoken says.

“Then we work together with the community to talk about solutions and actions.”

What’s in Whistler’s water?

Regulations and guidelines for water quality aren’t in the hands of one agency. Municipal, provincial and federal regulations apply. But the multi-level approach means monitoring water pollution for fish and human health isn’t clear-cut. Capacity is limited for testing, and priorities in government compete for attention. The Healthy Waters program fills gaps by looking at a broad range of contaminants of historic, current or emerging concern, and the results can contribute to “policies, practices and regulations at the local and national level,” according to Raincoast’s website.

“It’s a bit of a hodgepodge of different approaches to try to understand what’s going on in the environment,” Ross says of the varying regulations and guidelines. “There are different intervention steps that are possible along the journey back to Victoria and Ottawa to turn off the tap on a particular chemical that becomes a problem.”

Step 1 is identifying if a problem exists.

Whether it’s a tire-related chemical called 6PPD that kills off coho salmon, or perhaps less-expected contaminants like cocaine, DEET or lead, each tells a story about humans’ actions and represents an opportunity for individual, industry and government solutions.

Road run-off contaminants

Perhaps unsurprisingly, during the dry and wet seasons testing in 2023 and 2024, road run-off was the most contaminated category.

Contaminants included “nutrients, pesticides, per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, and 6PPD-quinone.” Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl are synthetic chemicals found in lubricants, paints and much more. There were no exceedances of available guidelines, which is positive.

6PPD-quinone comes from a chemical used on tires called 6PPD. When exposed to air, it creates 6PPD-quinone (6PPDQ). 6PPD stops tires from breaking down easily and helps them last longer. 6PPDQ is known to kill coho salmon. An accelerated review of the chemical is currently underway through Environment and Climate Change Canada, thanks to a request by Raincoast, the Watershed Watch Salmon Society, and the Pacific Salmon Foundation.

However, the review process won’t be finalized until June 2025. Ross says after that, there would be a phase-out and regulation, which also takes time. Plus, tires are on roads for about five years.

“This is a problem that’s going to persist for another seven or eight years, and it’s going to continue to kill coho salmon up and down the coast of British Columbia,” he says.

But there’s another solution in the interim. Researchers at UBC created special gardens called bioretention cells that remove up to 90 per cent of the chemical.

“The results are very encouraging … If you filter your road run-off in a storm system using natural wetlands and bioretention structures, etc., you can really remove a lot of the lethality associated with the road run-off,” Ross says.

Another interesting finding from Healthy Waters in the road run-off category is human waste.

“Either someone’s using ditches everywhere as toilets—which is, to a degree, possible—but I don’t think it explains the problem,” Ross says.

He postulates human waste is coming from leaking septic tanks or faulty connections in wastewater collection systems.

Septic tanks need to be emptied when at capacity, on average every three to five years for the typical tank. They can leak when clogged or too full, and waste ends up in places like drainage ditches.

While determining exactly where human waste is coming from is beyond the scope of Ross’ project, the findings will hopefully encourage local action from homeowners or the municipality.

Tap-water contaminants

Tap water was the least-contaminated water category in the wet season, but came in as the second-most contaminated category for the dry season. It had the “highest concentration of bisphenols, pharmaceuticals and personal-care products, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,” the report said. It also had one exceedance of Health Canada drinking water quality guidelines for lead in the dry and wet seasons.

It might seem odd at first glance to sample water from homes when looking at the health of a watershed, but Ross explains tap water is very much part of the picture.

“We want people to acknowledge that we’re part of the water cycle. We’re part of the watershed,” he says. “We’re borrowing water for our own purposes from fish habit, and we’re releasing it back in the fish habitat usually more contaminated [than when] it was brought in.”

Lead found in Whistler’s tap water was previously reported thanks to a Star-Global-UBC investigation. Homes built before 1989 with copper pipes have solder with 50-per-cent lead content. In 1989, the national plumbing code was updated, compelling plumbers to reduce lead to half a per cent.

There is no safe level of lead exposure, and chronic exposure for children ages three to five is linked to lower IQ scores.

Residents can test their water for lead at relatively low costs, and if homeowners can’t afford to replace their pipes, Ross suggests getting a charcoal water filter or running the tap until it turns cold. Cold temperatures indicate the water is coming from the municipal supply and is likely no longer contaminated from sitting in lead-laden pipes.

Then, there’s the pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) found in tap water, with four types found in the dry season. Penicillin, caffeine, bisphenol A and DEET were present.

“There’s no guidance. You cannot call Vancouver Coastal Health or Fraser Health and the Ministry of Health, and say, ‘Hey, is it safe to drink our water? Here is what I found,’” Ross says. “They will just have a blank stare when you say that. That troubles me.”

Without guidelines for acceptable concentrations, people are left to wonder what’s safe for them to consume.

“The non-scientist in me is going, ‘Are you saying it’s OK to have this in my drinking water?” Ross says. “We have some work to do.”

Bisphenol A, also known as BPA, was found in high concentrations in tap water during the wet season. It’s an endocrine disruptor which effects reproductive systems for aquatic life and humans. Single-use plastics and multi-use plastics have BPA.

The most likely cause, according to the report, is from household plastic pipes and/or the municipal distribution system. There are currently no guidelines from Health Canada for BPA in drinking water, and federal environmental quality guidelines for BPAs are seven times higher than what the researchers found in tap water. Minnesota’s Department of Health in the United States has drinking water guidelines for BPA, and Whistler’s was “well below” Minnesota’s guidelines, according to the report.

From homes to rivers and oceans

Using PPCPs means they also end up in municipal wastewater treatment plants, where wastewater is treated and then released into the environment and flows into streams and rivers. There were 14 types of PPCPs found in streams and rivers. Some, like penicillin, could come from inappropriately disposing of medicine by flushing it down the toilet. But there’s also evidence of metabolized cocaine, which isn’t removed through wastewater treatment plants.

“If you’re a little fish living downstream on the Cheakamus River, you would be exposed constantly to cocaine and metformin and penicillin, because they’re being released by the municipal wastewater plant, even at low concentration,” Ross says. “That’s pseudo persistent—where it might be breaking down in the environment, but they’re constantly exposed to it.”

When discussing the report, Ross reiterates that, all things considered, the watersheds in Whistler are relatively healthy. Very few results exceeded available guidelines, but the next two data sets will provide a clearer picture of samples’ validity by showing whether these are one-off results or represent a pattern.

“This report is merely a stepping stone in the incremental journey towards a better understanding of water quality and the threats areas face,” he says.

The Healthy Waters project also isn’t unique to Whistler. Raincoast is studying 10 other watersheds that drain into the Fraser River and Salish Sea, working with First Nations and community stakeholders. Eventually, researchers hope to develop a website that shows which contaminants are where.

“That will speak to each and every contaminant that represents potential concern in each watershed and what the priority could be in each different watershed,” Ross explains. “The caveat for that is, we’re not ready to do that yet.”

Before that happens, researchers need the data and trust from First Nations and communities.

“My experience has shown me the public, and in particular, Indigenous communities and Nations, are concerned about water quality, whether it’s drinking water or fish habitat,” Ross says. “I think that message gets lost often in the corridors of power.”

To build trust and provide real-time information to communities, Raincoast recently deployed a retrofitted cargo van, aptly named Tracker. The van allows for some testing in the field, and while many samples will still need to be sent to high-tech labs for results, having the mobile lab on hand allows for people to see what some results are and learn to test themselves.

“It was the No. 1 complaint I ran into. ‘Oh, you guys, you come in here, you do a quick study, and we never hear from you again,’” Ross says. “We bring the lab to the field, and we’re demystifying the activity, or sharing these opportunities for training and engagement and capacity building.”

The same is true for First Nations, which have historic reason to lack trust in scientists.

“Ditto for the many First Nations that we’re working with. They want science, but they also want it done in lockstep with Indigenous knowledge, and they want the ability to do things themselves,” Ross says. “They want more capacity, and that’ll give them more ability to track natural resource management issues or stewardship and restoration initiatives.”

Stay tuned for the full report, expected in 2025.