On a chilly October evening, I’m sitting at the back of the audience at an intimate gathering at the Whistler Museum of around two dozen people. A silent digitized film of skiing Whistler Bowl in 1963 (years before it was named Whistler Bowl) runs in the background as attendees comment and jeer at the skiers’ technique, laughter all around. Tables are littered with generations-old memorabilia, photos and newspaper clippings of Canadian ski-racing success stories. Some of those racers are here tonight, milling about and greeting old friends. Some travelled from the other ends of Canada and the United States; one flew in from England. Others drove less than 10 minutes to get to the Whistler Museum. This is the reunion of the 1964 to 1968 Canada National Ski Team.

“Everyone was so excited to get together,” says Karen Vagelatos, a two-time Olympian ski racer.

“My old roommate, Anne Rowley, flew in from London for the reunion and she stayed at my house here in Whistler. I hadn’t seen her since 1968.”

I sit back and take in the history of these hard-working skiers, coaches and administrators as they take turns with speeches. Throughout the night I learn how Canada first emerged as a global force in ski racing.

Born from necessity

Years before the international notoriety—and seemingly reckless downhill racing antics—of the Crazy Canucks, the first true national ski team had to first overcome Canada’s fractured ski development system.

The 1964 Olympics in Innsbruck, Austria was considered a poor performance by Canada. Nancy Greene was the sole top-10 finisher, managing a seventh in the downhill. In May of 1964, former Canadian downhill champion Dave Jacobs wrote a letter to the Canadian Amateur Ski Association (CASA), in which he voiced his concerns over his country’s ski development deficiencies.

“We have some tough problems to solve which require some slightly revolutionary solutions,” he wrote.

Jacobs had witnessed the well-oiled machines of European national ski programs in France, Austria and Switzerland, all nations that had full-time coaching staff, scheduled training camps and a development pipeline for their skiing youth.

The Canadian system at that time was far more dysfunctional. Canadian ski racers trained at their home hills then attended a selection camp before major international events like Olympics or World Championships. CASA would then hire a European coach to join the team on the ground when they arrived at events, often meeting the athletes for the first time then and there. This minimalist approach had worked for highly talented skiers such as Lucile Wheeler (Olympic bronze in downhill in 1956, World Champion golds in downhill and giant slalom in 1958) and Anne Heggtveit (Olympic gold in slalom and World Champion gold in combined in 1960), but it was not a recipe for consistent success.

Jacobs opined that it was time for Canada to develop a new national team program, where young skiers could attend university on a scholarship and train year-round with dedicated, full-time coaching staff. Don Sturgess, chairman of CASA’s alpine competition committee, knew all too well that drastic changes were needed if Canada was ever going to assert itself as a skiing nation. He replied to Jacobs’ letter saying CASA was likely to set up a program at Notre Dame University (NDU) in Nelson, B.C., and asked if Jacobs would be interested in coaching the team. NDU was considered the best suited institution to host the new program, which was dubbed the “Education Plus Competition Experiment.” The university had recently implemented Canada’s first athletic scholarship program for its hockey team and Nelson was the ideal location with two nearby ski hills; Rossland’s Red Mountain and Nelson’s Silver King (the predecessor to Whitewater). Importantly, Nelson also had the nearby Kokanee Glacier where the team could train during the summer months.

In the summer of 1964, 15 men and 10 women were welcomed into the dorm at NDU as the first Canadian National Ski Team, coached by Jacobs and managed by assistant athletic director Peter Webster. Among them was Greene and now longtime Whistler locals Barbie Walker, Bob Calladine and Karen Vagelatos (née Dokka). Jacobs introduced high-intensity dryland training to the team immediately, not as much for the upcoming ski drills but for the arduous hike to the Kokanee Glacier, their designated training venue that summer.

“I’d never been to summer camp before, so Kokanee Glacier was a whole different kettle of fish,” recalls Walker, who was 17 when she arrived in Nelson. “It was crazy. We slept in tents and would hike up to the glacier with skis on our backs at 6 a.m. while the snow was firm. The second year there was a gas-powered rope tow up on the glacier, so we could get more runs in. We all had to carry a metal handle that would clip to the wire cable.”

After a full day of ski training, the campers rewarded themselves with a swim in the frigid glacial lake, followed by a sauna. A group of the skiers including Calladine had managed to find an old pot-belly stove and ported it up the mountain, creating a makeshift structure with three plastic walls against a large boulder, with a flap for a door.

“The summer camp was something I’ll never forget, it was amazing,” says Walker.

It was these experiences—skiing together, eating together, training together, suffering on long hikes together—that began to unify these young Canadians.

“The program at NDU is what got us into a proper team spirit,” says Calladine, who years later coached a young Steve Podborski in Southern Ontario. “Before that it was a lot of East versus West, and the East had the money. I’d raced against all those guys in juniors, and it was fiercely competitive on the ski slope. Us B.C. skiers got along with the Albertans because we’d often travel together, but it was in Nelson where everyone started to feel like they were together on a true Canadian team.”

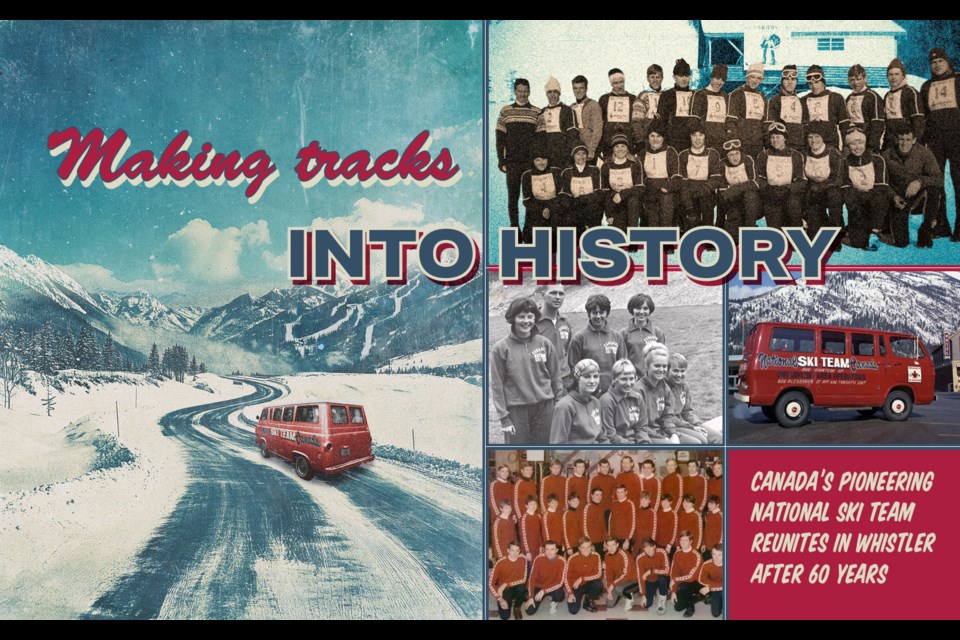

This pride and patriotism was also reinforced by what the skiers wore and how they travelled. The national team had never even worn the same uniform before, but with the advent of the Nelson program, the entire team not only started acting like they belonged together, but started looking like they belonged together.

“Symbolism was important,” says Jacobs. “I designed sweaters and helmets for the athletes to wear that had white stripes and maple leaves. I convinced Volkswagen to donate buses for the team and when the public saw them disembark, they’d see these kids unloading professional looking ski bags with ‘Canadian National Ski Team’ logos on them. I wanted the athletes to feel like they were part of something bigger than themselves.”

The team was still in building mode for the 1964-65 season, so they focused on racing in North America only. Jacobs brought along eight young men and nine young women to the 1965 Roch Cup Championships in Aspen. Even their travel to Colorado showed real grit; piling helmets and skis into two Volkswagen buses, driving four hours to Spokane, taking a 30-hour train to Denver where they then rented three cars and a station wagon and drove another six hours to Aspen over snow-slicked roads.

The results in Aspen spoke for themselves. Seemingly out of nowhere, the Canadians were on the podium beating out American Olympians. Greene won the alpine combined, the 21-year-old smashing the female field.

“We did not come here to win everything in sight—this time,” Jacobs told Sports Illustrated in the 1965 article “Canadians Raid Aspen.”

“But we will win in the future. Watch us. This is our first year under a new Canadian program. It should get results. We copied it exactly—and unblushingly—from the Americans.”

The Next Chapter

By the 1967-68 season, the Nelson camps had begun to run their course. Jacobs had left the team to go work for Bob Lange, who was developing high-performance plastic ski race boots that would soon dominate the World Cup circuit. Greene had a hugely successful 1967 season, winning six races and the first ever women’s overall World Cup title, breaking the European domination of the sport. She won the World Cup title again the following year, as well as a gold medal in giant slalom and a silver medal in slalom at the 1968 Olympics in Grenoble, France. Greene retired after the 1968 season and her soon-to-be husband Al Raine—who had taken over as head coach—moved the program out of Nelson to Montreal. The consensus between Raine and CASA was these young skiers needed more time on snow and less time in classrooms.

Canadian skiers had proven their worth on the world stage and both federal and provincial bodies were now more willing to support athlete development programs. While the move away from the scholastic-athletic program in Nelson was arguably the best decision in terms of producing more World Cup-level skiers, the 1964-1968 national team members benefited immensely from earning an education while training for high-performance competition.

“The kids that went to that four-year program got an undergraduate degree, with a lot of them going on to become doctors, dentists and successful businessmen and women,” says Walker, who herself attended Kootenay School of the Arts during the program and went on to become a career art director in Montreal. “They were all successful people, and many of them were inducted into the Canadian Ski Hall of Fame.”

Much of the drive to blend school and ski-race development came from Jacobs himself, not only to set up the program at NDU, but to sustain the educational element throughout the busiest times for the ski racers.

“Imagine a national team going to Europe for a World Cup race, with a tutor tagging along,” says Jacobs. “That’s how important I felt academics was, I wanted them to be more than just ski racers.”

Vagelatos had her own academic journey following her years in Nelson, studying at UBC before going on to graduate school.

“When I applied to UBC it was all in person, not online like today,” she recalls. “They asked what I’d been doing since high school and I said, ‘I’ve been on the Canadian ski team the last four years.’ They said, ‘OK, you’re in.’ It was the same thing at the University of Michigan. What it says to people is that you have this commitment to excel. It very much carried through from ski racing to education. Had we not had those years in Nelson, who knows? If we hadn’t had (Jacobs’) vision, it may not have ever happened.”

Sixty years ago, youths from all over Canada turned up in Nelson knowing little about what lay before them. They built friendships, represented their country on the world stage, became educated and most importantly, bonded over their passion for skiing. While maybe not as agile on the slopes as they used to be, these Canadian ski-racing veterans are still making turns.

“Skiing has been my whole life,” says Walker, who coached the senior ski team at Whistler Blackcomb and made many trips to Whitecap Alpine’s McGillivray Pass Lodge over the years. “It’s who we are as a family.”