There was a time, back in the early ’90s, when (some) locals were thrilled with Whistler being listed at No. 2 on Ski Magazine’s list of best North American resorts.

Then, when the resort made it to No. 1 in 1996, there was definitely a feeling with locals that Whistler was finally being recognized for what a great destination ski area it was. But as the saying goes, be careful what you wish for.

In 1990 the Fairmont Chateau Whistler had just opened, Phase 2 of the village was still years away, and Whistler Mountain was still a separate entity from Blackcomb. The idea of Whistler as a jet-setting international resort was not yet fully realized.

While the first “monster” chalets went up in the mid to late ’80s, the early-’90s recession had cooled off the real estate market, and first-generation A-frames and gothic arch cabins continued to make up most of the valley’s single-family homes.

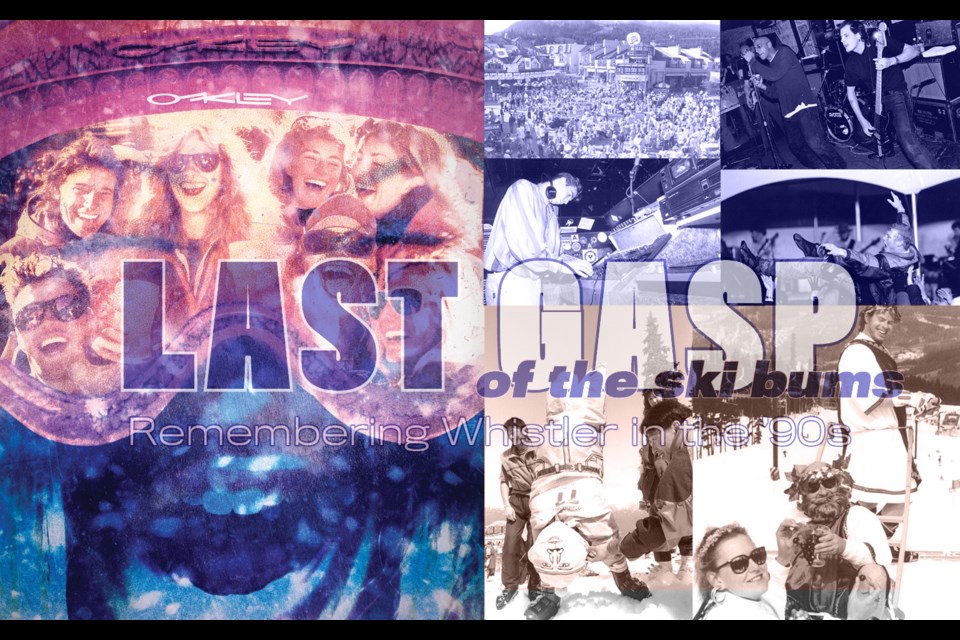

In that environment came (so some say) the last gasp of the ski bums or “dirtbag” skiers who first popularized Whistler starting in the late 1960s through the ’70s.

JOIN THE DARK SIDE

One of those Whistler originals is Jan Simpson, who first came to Whistler in 1969 and was driving the Sea to Sky highway to Whistler before they had even finished paving it.

“Whistler was where I skied. [Then] when Blackcomb was established I skied both. I always had a dual-mountain pass,” Simpson recalls. “We used to call Blackcomb ‘The Dark Side.’ But I think most people were excited to have two first-class ski mountains outside our door—we were the envy of everyone.”

Blackcomb Mountain and the original Whistler Village opened in 1980-81, alongside Whistler Mountain, which opened in 1966. Blackcomb was started by the Aspen Corp, which originally had high hopes for the mountain. But plans change, and Aspen Corp sold out to Intrawest in 1986, which then acquired Whistler Mountain in 1997. In the intervening years, many locals felt a loyalty to Whistler Mountain, such as artist Christina Nick, who arrived in Whistler in 1990.

“There used to be a healthy rivalry between Whistler and Blackcomb, which made it pretty fun to be here. I primarily skied Whistler, and when Blackcomb opened, you could choose to have a ‘Dual’ mountain pass. There were people who even asked where they could find ‘Dual’ mountain, since they could not understand why they only saw the names ‘Blackcomb’ or ‘Whistler.’ It was the start of many jokes,” recalls Nick.

The merger of Whistler and Blackcomb mountains into a single corporate entity has changed the operational dynamics of the resort, but the biggest difference between Whistler now and in the ’90s, according to Nick, is the shift from a primarily ski-focused destination to a more diverse, year-round resort catering to a wider range of visitors.

In the ’90s, Whistler was known for its epic snow winters, and the summer activities that exist now (hiking, mountain biking etc.) were a byproduct, not the reason for being in the valley. The resort was primarily focused on winter-sport enthusiasts, with a strong emphasis on skiing and the emerging snowboarding culture.

Today, Whistler has evolved into a multi-faceted destination with many things to do all year round.

THE DOMINO EFFECT

Former competitive snowboarder turned local business owner Justine Ewart feels (like many who were here then) the influx of money, an inevitable result of the resort’s popularity, is behind the most noticeable changes between then and now.

“I would have to say [it has had] a domino effect. The prices rising … which eventually moved out the heart of this town and its vibe, and since has been replaced with money people who invest in their future or a fun time,” she said. “If you can afford it, that is wonderful. But it would be lovely to see a diverse portfolio up here so to speak. It’s a rat race now. Everything is moving too fast and there is no ‘in the moment’ vibe anymore, or chill.”

Ewart says her first day on the hill when she came to Whistler was on Blackcomb, but after that she became “a true Whistler Mountain rider.” Like many who were here at the time, she wasn’t crazy about the two mountains merging—but thinks it pales in comparison to the Vail Resorts purchase of Whistler Blackcomb in 2016.

“I don’t think it was a good thing (the original Whistler/Blackcomb merger). But I also don’t really know. I feel Vail has done way worse,” she said. “It has overshadowed everything beforehand. However, with Vail as owners the mountain is a lot less busy. Except for holidays.”

Simpson echoes that sentiment, saying the most substantial change from the ’90s till now is the Vail Resorts takeover of Whistler Blackcomb.

“I’m grateful to have had the best days of Whistler before Vail, [with the] congested highway, [frequent] closures due to crashes and fatalities,” she says. “[They were] the good old days!”

David Buzzard, a local commercial photographer/photojournalist whose family owned the old campground in Whistler, agrees money has changed Whistler—not just the practicality of housing costs, and other cost-of-living expenses, but the feel of the resort overall.

“The size of the resort has grown so huge that most of the characters who lived here in the 1990’s couldn’t afford to live here, or probably wouldn’t be interested in living here if they could afford to,” Buzzard says.

He also agrees the Vail Resorts purchase has not been great for Whistler as a whole.

“I think the merger of Whistler and Blackcomb was bound to happen and made Whistler into the truly dominant resort it was until Vail took control,” Buzzard says.

LIVING LODGE

One of the major impacts of the stratospheric real estate market, and resulting development, is the removal of squats. In the ’90s, squatters’ cabins, a part of the Whistler scene from the beginning, were still widespread throughout the valley. Even on the shores of Alta Lake, near Lakeside Park, thrown-together cabins on unowned land were visible.

“I had good friends who lived in Jordan’s Lodge, where The Nita Lake Lodge sits now. It was a crazy place, always a big party on the go. It was sinking into the ground, so none of the floors were level,” says Buzzard.

Nick also remembers many of the Whistler squats back then, some of them near-legendary.

“The [end of] squats in Whistler indeed represents a significant change in the town’s character and culture. The era of squatting in Whistler marked a time of youthful idealism, adventure, and a more carefree lifestyle that seems impossible in today’s Whistler,” she says. “In the 1990s, Whistler had several popular areas for squatters. [They] included the squats near Parkhurst and on the Green River. I visited ‘John’s Garden’ many times in the 1990’s and canoed over from Emerald Estates very often to tend the plants, sketch and hang out.”

The classic ski-bum lifestyle was epitomized by figures like Charlie Doyle, a prominent figure in Whistler’s squatter community and founder of the legendary Whistler Answer, and John “Rabbit” Hare, who lived with his family in a hut at the top of Whistler Mountain, so he could be first on the lifts each morning. Everyone knew Rabbit, and had danced with him at the Boot, or another party in town.

Some dirtbags lived in unofficial settlements, such as the famous Toad Hall at the north end of Green Lake.

The era was known for legendary nights and colourful characters, including Seppo Makinen and his unforgettable parties.

Seppo lived in a massive log house on Nesters Road, which became a local landmark. He built it using recycled materials, including doors from Vancouver’s old city hall and flooring from the former Woodfibre (the old Squamish pulp mill), bowling alley and gymnasium. The house had an eclectic and unique character found nowhere else in town.

It was crammed with old ski equipment, clothing, records, books, games and trinkets, many left behind by transients. His hot tub always had someone in it, often for what seemed like days or weeks at a time.

Seppo ran the house as an informal lodge, enjoying the company of colourful transients to whom he rented rooms. His parties in the ’90s were always off the rails, and included a tour of the premises by Seppo for first-timers, and a rotating door of Whistler celebrities and well-known locals. Seppo was a crucial social figure in Whistler, along with Rabbit.

Tragically, Seppo’s iconic house burned down on April 19, 1998, leaving him essentially homeless. We watched the smoke and flames from Nesters, and knew then that an era had passed with the eradication of his home.

Ewart says she doesn’t remember visiting any Whistler squats, though some of the places she lived in back then could be described that way.

“It was simple. There were always 7-10 people per home and rent was decent. Food costs were decent,” she says. “If you weren’t sponsored, you could work part time and ski/snowboard lots.”

THE PLACE TO BE

One of the old Whistler landmarks most missed by locals is the old Boot Pub and Hotel. Located just north of the village, back in 1970 when it opened it was a little off the beaten track. Still, locals flocked to it, and by the ’90s it was a Whistler institution.

“The Boot was always the place to see friends and have a couple of drinks. It wasn’t unusual to have a cowboy on a horse walk through the front door, sometimes even when the strippers were on stage,” remembers Simpson.

Buzzard has his own special memories of The Boot.

“Do I ever miss The Boot. My family owned the old KOA Campground, where the Spruce Grove neighbourhood is now, so we could walk over to it,” he says. “I had a cat who used to wander over to the Boot during the Boot Ballet strip shows and drink beer out of the glasses of the guys watching the strip show. I would get a call from the bartender at the end of the night to come pick up my drunken cat.”

Monday nights at The Boot were epic, Buzzard adds, with kicking live bands, $1 pints and $5 pitchers.

“You would see guys walking around drinking right out of a beer pitcher. It wasn’t uncommon to see someone passed out cold in front of a urinal, so you’d have to step over them to relieve yourself,” he says.

But Nick has perhaps the fondest memories of the now long gone Boot Pub, which closed its doors for the last time on her birthday, April 28, 2006.

“I had a wicked birthday party that night, and helped close its doors. It was a great party, but a sad one as well, the end of an era,” she says.

“I believe the closing of the Boot had a notable impact on Whistler.”

It was a loss of a cultural landmark, since the Boot Pub was more than just a bar; it was known as the “locals’ living room” and played a crucial role in nurturing Whistler’s famed ski culture. Its closure meant the loss of a place that captured the local lore of Whistler across three decades.

Its closure also removed one of the few remaining budget-friendly hotel options in an increasingly expensive resort—and one of its best venues for live music and entertainment. Over the years, The Boot hosted both famous bands like The Tragically Hip (a.k.a. the Fighting Fighters), Michael Franti & Spearhead, Nickelback, Watchmen, DOA and other up-and-coming artists. Its closure left a yawning gap in Whistler’s music scene.

DIRTBAG DEMOGRAPHICS

As these longtime locals have noted, squats and social institutions like The Boot Pub were pretty much at their end as the ’90s drew to a close. As the resort evolved, many of the dirtbag skiers—with their philosophy that if you were just skiing the lifts, then you weren’t skiing—began to look elsewhere.

“The dirtbags were a bunch of young guys who threw off the professional skier scene. They all worked construction or something in the summer and lived in old communal houses or squats that were really cheap, so they could ski through the winter,” Buzzard says. “The dirtbags also combined mountaineering with the beginning of the extreme ski scene. Whistler just became too crowded and expensive to be a dirtbag and most of those guys have moved away to smaller ski resorts.”

Of course, for anyone who was here in the ’90s, it was, in the end, all about skiing (or snowboarding). So what was it like then, before millions of visitors each year descended on the mountain?

“For me the best times to ski were during snowstorms… of course,” says Nick. “But I also recall the wonderful spring skiing we had in the 1990’s, with true corn snow, endless long sunny days, Mouton Cadet festivals, and plain ol’ raucous skiing, with not a worry and no real commitments. That was a wonderful time to be alive.”

SUMMER LOVIN’

One of the major differences between the ’90s and now is the summer season. By the ’90s Whistler had developed most of its lakeside parks, but there weren’t throngs of people filling them.

“Summers in Whistler in the ’90s were great. You could find a party with a huge bonfire in the backyard any day of the week. Now they don’t even let you light fires anymore,” remembers Buzzard.

It was the days when Whistler still experienced a true dead season, as tourists became sparse in the summer months.

“When the skiing ended in the spring, suddenly we, the locals, were alone. Everyone who lived in Whistler came out of the woodworks and we had many, many staff/local/bar wars parties that forged even stronger friendships over that time,” says Nick. “The bars and restaurants that stayed open had a friendly rivalry that encouraged us to come and spend our cash there with very low prices for meals and drinks. If you were still kicking around after the mountains closed, you were a local, and worth knowing.”

Nick and her friends would ride bikes and hang out by local lakes, often staying past dark to watch meteor showers.

“It was all very fluid and organic back then. Whoever was there, was there,” she says. “No one used a cellphone to call people, we were happy to just be in that spot at that moment with those people.”

Ewart mostly recalls the peace and quiet after the craziness of the winter season.

“They were so quiet. The shoulder season lasted for a solid two months, easily. Now we are lucky for two weeks in the spring,” she says. “And at least one month in the fall of quiet time. Lots of parties, lots of lake and activities. The lakes and parks were so peaceful.”

MARKET FORCES

But what about getting into the real estate market then, before prices became out of reach?

Buzzard did just that, although few working mainly service industry jobs could afford, even then, to get into the market.

“When my family sold our business, I had enough to put a down payment on my house in 1997. I was able to pay it off as a photographer, but I think I was the last generation of working class locals who could buy a market house,” he says.

Ewart, now married with children, does have a few regrets about not planning a little more for the future back then.

“It was really possible. If we only knew then what we know now,” she says. “We all would’ve scraped together everything we had and made smart investments to get to where people 20 years older than me are now.”

A single-family home could be had for less than $400,000 in the early ’90s. Even at the end of the decade, a two-bedroom townhome could be found for about $200,000. However, as Ewart, who now runs her own business, points out, real estate didn’t appear to be the slam dunk it does today in hindsight. The local real estate market had crashed in the early ’80s, and taken a downturn in the early ’90s. So for those working service-industry jobs to scrape together every last penny for a down payment on an investment that might become a liability, it was a gamble most didn’t want to take.

Nick is fatalistic about what might have been.

“I knew people that bought houses back then in the 1990’s, but most of them were older than me when I arrived, and had their lives figured out,” she says. “I, on the other hand, arrived in 1990 and had barely enough money to pay rent and a bag of rice, much less think of buying anything in the valley. That remains true to this day. Sometimes things are about timing. But I still wouldn’t change a thing.”

Simpson, who became a real-estate agent in 1979 while working as a bartender at the Cheakamus Inn, had already made the jump to home ownership by that time.

“The first house I owned was in Alta Vista on Tyrol Crescent (locally known as Tylenol Crescent). In l972 I think we paid $70,000 for it.”

In the ’90s, or even back to the 1980s, there were many who perceived Whistler as Aspen North. But as those who were there tell it, that was far from the truth.

“I was under the impression that people considered Whistler a rich person’s place, not a place that you could make a home in,” Nick says. “People did not understand about the deep, rich community in Whistler. Many of my friends that did not live in Whistler could not understand my choice of living here, thinking it was a soulless place driven by luxury and fashion.”

For Nick, that was never the case.

“The community in Whistler, I feel, was and is a strong, supportive unique group of people from many walks of life, with a variety of interests and have proven to always be helpful and caring,” she says. “Now, I believe people feel the same way, that it is the place of the rich, and still do not understand about the ‘hidden’ community at its heart.”

She admits back then it was hard to see just how big Whistler would become as a destination resort.

“The popularity of Whistler crept up on all of us,” she says. “But I knew that there was a good thing going, and was not surprised with the popularity of the resort.”

Buzzard says even in the heyday of the dirtbag skiers, Whistler was seen as an international resort along the lines of Zermatt or Vail, and all that brings with it.

“Whistler has always been perceived as an enclave for the wealthy, but in the ’90s the average young person could really make a good life here. [But] even before the end of the 1990’s it was becoming too expensive for most of the traditional locals,” he says.

“I remember the event for when Whistler/Blackcomb first broke a million skier visits, and thinking this is getting to be too much. Today I think it’s about four million skier visits a year. The ’90s was 30 years ago, so Whistler has evolved into something totally different today. My wife, who moved here in 1999, doesn’t believe me when I talk about the old days.”

Ewart says she felt on some level the Whistler she knew was never going to last, it was just a matter of how long everyone had.

“I never really thought about it. But subconsciously, yes, it was a pretty amazing place, and everyone wanted a piece and everyone wanted to be here,” she says. “So I would say, yup, I knew it was coming.”

But still, Ewart points out, there will always be people here that will say now is the best time, or in the years to come, they will remember their time here that way. Every generation coming through Whistler is experiencing it for the first time, and so it’s all new and exciting, just as it was 30 years ago.

“Back then we all looked at it through rose-coloured glasses. Today they are darker,” Ewart says. “However it is relative, if I was a 20-something year-old travelling here for the first time, this place would rock just as awesome as it did 30-something years ago. It’s all how you want to feel about it.

“Today I am a wife, mother and self-employed hard working woman in this town. I would change nothing. And I hope those around me at my age would feel the same. You won’t find any other town with this vibe and this much work. You just need to learn how to navigate ‘yours’ without burning out.”