Photography has long served as a powerful tool for documenting and preserving human history. From its invention in the early 19th century, photography revolutionized how people recorded the world, capturing moments in remarkable detail and making them accessible to future generations. The ability to visually document everyday life, historical events, and personal milestones has transformed our understanding of the past.

Some of the earliest photographs of the Whistler area date back to 1911, when Myrtle and Alex Philip made their three-day journey from Vancouver to Alta Lake via the rugged Pemberton Trail. The Philips played a pivotal role in shaping Whistler’s early tourism through their operation of Rainbow Lodge, the area’s first tourist attraction. The couple’s photographs provide invaluable snapshots of a formative era in Whistler’s history. Their photos helped document milestones such as the arrival of the railway, the first airplane landing on Alta Lake, the start of industry such as logging, and the evolution of community life in the area. These make up some of the Whistler Museum’s most prized images.

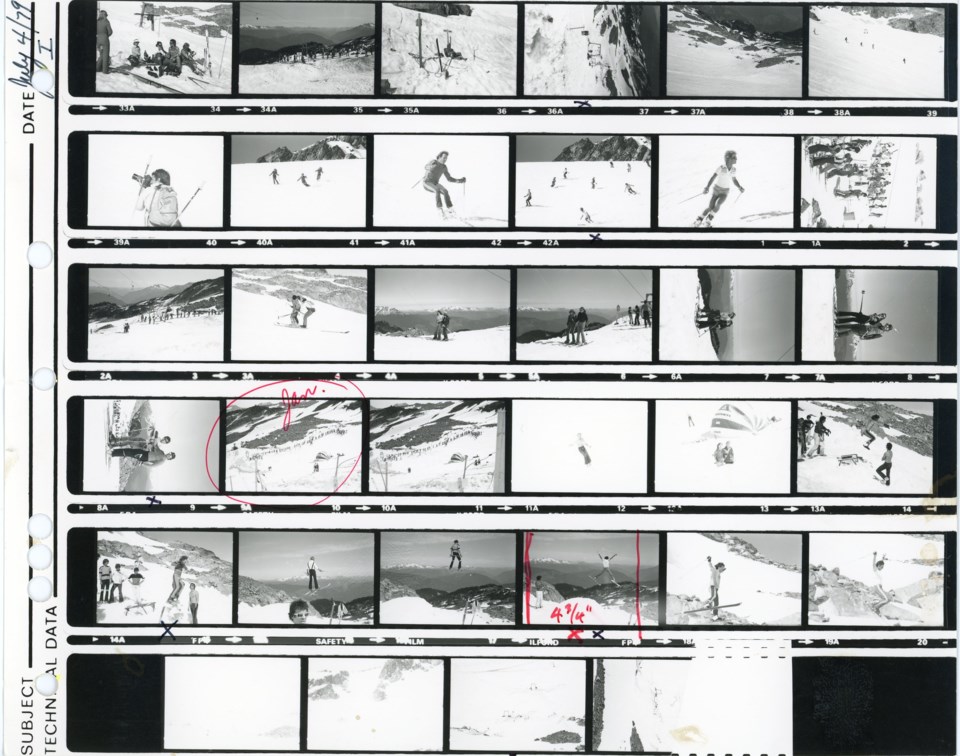

With a collection of more than 300,000 physical photographs, the museum’s photographic holdings are its largest and one of its most valuable assets. This collection spans decades, chronicling everything from the first documented mountaineering trip in 1923 (rich with photos of now long-since-receded glaciers) and the development of skiing in 1965, to the design and construction of Whistler Village in 1979-80 and hosting the 2010 Olympic Winter Games. Through these photographs, museum staff, visitors, and researchers can explore Whistler’s rich heritage.

Prior to the advent of digital photography (widely adopted during the 2000s), images were captured using a light-sensitive chemical emulsion applied to glass or to a strip of plastic or paper, commonly referred to as film. The process began when light entered the camera (sometimes just a crude wooden box) through a lens and exposed the film, creating a latent or hidden image. This latent image was then revealed during development, where the film was treated with specific chemicals in a darkroom to make the image visible. Once developed, the film could be used to create prints by projecting the image onto photographic paper.

Film types, emulsions, and the chemicals used for developing evolved significantly over the 20th century. One of the most important advancements was the development of safety films, which replaced the highly flammable and unstable nitrate films that were widely used prior to the 1940s. (The dangers of nitrate film and its combustible properties were a major plot point in the 2009 Quentin Tarantino film Inglourious Basterds.)

Tragically, many films from the silent film era of the 1920s were lost forever due to fires caused by nitrate films. One such loss is The Crimson West (1933), Canada’s first talkie film (a film with audio). Based on one of Alex Philips’ novels, it is considered a lost film after the Capitol Theatre in Victoria burned down, destroying the last known copies. Fortunately, aside from a few nitrate film negatives stored safely and securely, most of the museum’s collection consists of prints and safety film.

Our photographic holdings include a variety of formats, ranging from black-and-white images made from 4”x6” medium-format film to the more common 35mm colour negatives, a popular choice among both amateur and professional photographers. Many of our collections also feature slide film, which were frequently used by businesses and families for presentations or “slide shows.” We ensure the preservation of these photographs by adhering to archival best practices, including careful handling and storage in acid-free archival boxes and stable plastic sleeves.

Photography, as documentation, is a bridge between the past and present. In Whistler, it continues to play an essential role in preserving the stories that define this extraordinary place, and we are glad to share these images with you here and on the museum’s social media channels. If you have photos you’d like to contribute to our collection, we’d love to hear from you—feel free to reach out or visit us at the museum!