If Whistler wants to act urgently to meet its climate goals, Edgar Dearden of sustainable building company GNAR Inc. has a few suggestions.

He sees the inefficiencies in nearly every project he gets hired to consult on these days.

“This building is heated by gas, it’s thermally bridged to hell, it’s just going to be polluting for the foreseeable future until they retrofit it … and this one won’t be built until 2022,” Dearden said, of one recent project he was brought in on.

“Why did you build a high-polluting building that’s going to contribute to climate change for 30 years? We’re supposed to be net-zero in 30 years, so either we’re going to retrofit that building or you’re just inherently saying we’re not going to hit the targets.”

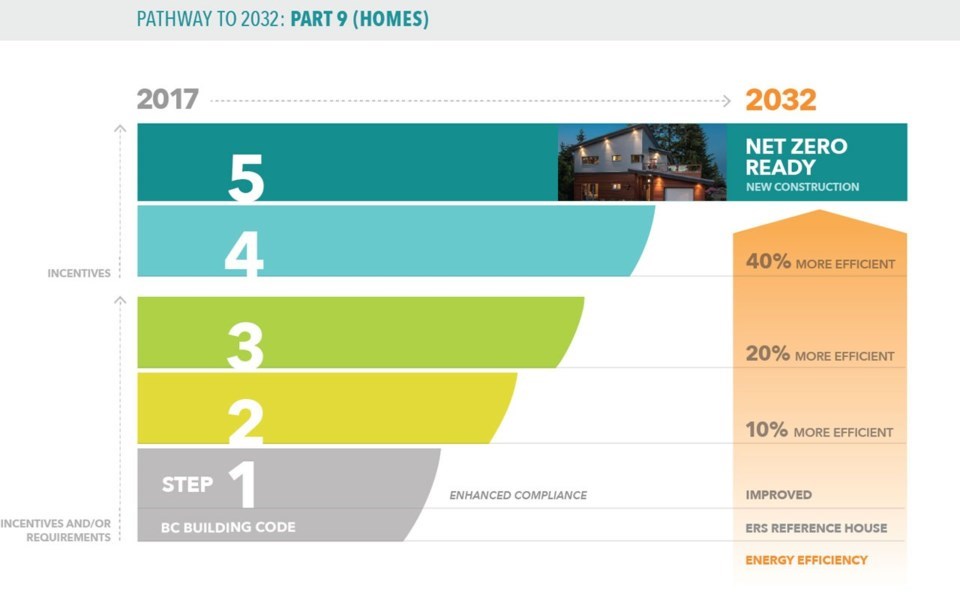

Whistler adopted Step 3 of B.C.’s Energy Step Code (ESC)—requiring single-family builds to be 20-per-cent more efficient than the base BC Building Code—in 2019.

In its new Climate Action Big Moves Strategy adopted last year, the resort targeted 2030 for a move to Step 5 of the ESC, requiring all new buildings to use only low-carbon heating systems.

But until staff and council officially change municipal policy, there is little incentive for builders or owners to go above and beyond, argues Dearden.

“My question today is should we be giving permits to all of these projects that currently keep applying for permits, given that every time we issue a permit, and subsequently a house is constructed, that potentially locks in 30-plus years of unacceptable emissions,” Dearden asked at the Oct. 5 council meeting.

And while council looks for game-changers or magic levers to reduce emissions, the answer is clear to Dearden.

“It’s removing the fossil heating systems, achieving Step 5 or passive house, all-electric buildings—that was my first inclination to your questions of how to achieve it,” he said.

Every year, GNAR Inc. takes on 20 to 30 clients “that I have to individually talk down from their initial impulse to use fossil gas heating systems. It’s a lot of energy I have to give on a daily basis in operating my business,” Dearden added, before asking if council is considering banning the use of fossil gas to heat houses in Whistler.

The Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) is considering a suite of options in relation to the Big Moves Strategy, said general manager of resort experience Jessie Gresley-Jones, but wants to be realistic about what can be changed short term.

“I think [banning fossil gas] definitely fits the ultimate aspiration. Getting to that outcome is going to require incremental steps, and so we’ll be looking at how to start shifting the dial,” Gresley-Jones said.

The building sector represents “a big segment of the challenge ahead of us,” but as it relates to the more than 250 permits currently being processed at municipal hall, “shifting the goalposts mid-stream can be challenging,” Gresley-Jones added.

“So we need to be clear with the sector up front, so that they can plan appropriately and we can have consistency across our industries to all be working towards the same target, and that does ultimately take time.”

The RMOW is working on a comprehensive update to its green building policy, which will include a Step Code implementation road map, Gresley-Jones said.

“We will be undertaking stakeholder and public engagement as part of the policy update,” he said.

“We want to be able to provide clarity and a clear sense of timeline for the industry so they know when we anticipate adopting higher Step Code requirements.”

As for how builders are navigating the current Step 3 requirements, “I think it’s somewhat all over the map,” said Bob Deeks, president of RDC Fine Homes.

For builders well versed in high-performance, energy-efficient techniques, it’s been simple.

“To builders who had never gone through that process of doing an energy model and building differently, there have certainly been some struggles, particularly with air tightness,” said Deeks, who sits as chair of the Canadian Home Builders Association’s National Technical Research Committee and vice chair for the Net Zero Housing Council, and has been involved in B.C.’s Step Code development and implementation since the early days.

The two barriers to wholesale adoption are education and capacity, Deeks said.

“So getting people up to speed … that’s why the code was introduced in a stepped approach, so municipalities could start at Step 1 that just required you to model your house,” he said.

At Step 1, which was essentially an education piece, there were no standards to meet, but builders would have to do an airtightness test, which would give them valuable insight into the quality of their current builds.

“I think that’s one of the most valuable aspects of this Step Code approach,” Deeks said.

“Rather than one day you don’t have to do any air tightness and then the next day you’ve got to comply to something that is so foreign to you that you have no chance of success, it’s allowed people to practice without any penalty at that step in level.”

Chris Addario, president of the Sea to Sky branch of the Canadian Home Builders Association, offered a similar sentiment.

If Whistler were to jump to Step 5, “I think at the end of the day we would get there, but it would probably cause [challenges] for some builders,” Addario said.

“Moving in a stepped fashion allows people to adapt, and I don’t think that’s a bad thing … I don’t think [Step 5] is a significantly high bar, but it’s still challenging for some builders and some owners to get there,” he said.

“[And] it does add costs, there’s no question.”

With that in mind, changes to legislation tend to drive implementation, Addario added.

“When it’s optional, it takes a little longer,” he said, pointing to things like triple-pane windows.

“Everybody knows it’s a good thing to put triple-pane windows in, but the code didn’t require it, and therefore it didn’t really happen. But now you pretty much have to use triple-pane windows to get to some of the numbers you need, so it makes a difference.”

Councillor Arthur De Jong, a longtime advocate for climate action and overseer of council’s environment portfolio, agrees with Dearden on the need for urgency, but hopes to find a “sweet spot” in terms of implementation.

Sustainability is about weighing the social and economic impacts alongside the environmental initiatives, De Jong said.

“I’m not comfortable [with the current pace]. I have to find the sweet spot … I see this with many environmental initiatives; if you push it too fast, without understanding the economic and design implications, it often falls backwards,” he said.

“So the question is, what is the most functional pace to get to where we need to get to? But I would agree that that pace is not fast enough right now.”

For Dearden, the plea to council for expediency was born out of a sense of being overwhelmed—he estimates about 80 per cent of new homes being built in Whistler are using gas heating.

“I’m spending all this energy just convincing my own clients to not do this, and then on the turn of a dime, I pick up some consulting work on other people’s projects, and they’re just doing it all anyways,” he said.

“So what difference does it even make if we convince our clients to build Step 5 all-electric if the house next door gets built Step 3 all-gas?”

A July 2021 study by the Pembina Institute suggests that, to decarbonize existing buildings in Canada by 2050, a zero-carbon “renovation wave” will be required to retrofit all buildings built between now and 2030.

There is currently no intention to require existing buildings to meet future energy codes, “so everything that gets built today will not be forced to upgrade for energy right now—recognizing things change,” Deeks said.

There is a renovation standard coming for energy efficiency in the next couple of years, but “there has been very little discussion, and nothing has really been established on how you identify where in that renovation scope you would start to drive energy efficiency,” he said.

But with 51 per cent of Whistler’s 2020 emissions coming from the built environment, moving to Step 5 right now would help “future-proof” the community, and save homeowners from having to pay for potential future renovations, Dearden said.

“Anyway you cut it, if you’re going to hit any of these [climate] targets, you need to get started on some sort of serious retrofitting program,” he said.

“And certainly to stop adding to the list of houses that will require those retrofits would be just common sense.”

Dearden also feels the cost argument is disingenuous, and that an energy-efficient, simple building can be built for less than an energy-efficient building with a “unique” design.

“Designing unique buildings is not a right—it’s a privilege, and it is not something our community should be subsidizing,” he wrote in a letter to council.

“If architects want to design these unique buildings, then they should justify them by building them to net-zero standard.”