On a rainy Friday this month, industry executives and government officials were sitting on the fourth floor of a Vancouver casino hotel. From the stage, a pitch for the future of forestry was on repeat: what if logging companies could be the heroes who saved British Columbia from wildfires?

Many of the speakers at the annual B.C. Council of Forest Industries (COFI) convention focused on how the sector could return to higher levels of harvest or slow the pace of government regulations. Then the conversation turned to wildfires.

David Coletto, head of the market research firm Abacus Data, presented the results from a poll he designed with COFI. After Canada’s most destructive wildfire season on record, the results suggested the B.C. public was ready to accept a narrative that the forestry industry could act as a saviour.

As Coletto put it, everybody in this province agrees who is the villain: it’s the fire.

“And so now you have a place to be a hero in that story,” he said, speaking to members of the logging industry in the room. “That’s a complete paradigm shift to where you were a few years ago, where you were often seen as the villain.”

Leaning on the data, COFI president and CEO Linda Coady said B.C. needs a “compelling story” that attracts investors, one that describes a convergence between fixing wildfires and increasing the supply of wood fibre.

Jamie Stephen, the managing director of the energy and resources consulting firm TorchLight Bioresources, put it another way.

“Counterintuitively, if governments and the public want forestry to contribute to climate mitigation in Canada, we have to harvest more, not less,” he said.

Does logging more prevent wildfires?

The call to re-frame forestry as the solution to wildfire comes less than a year after the most destructive season in Canada’s recorded history burned an area roughly half the size of Italy.

Experts interviewed for this story agreed the best solution to a growing wildfire crisis is to reduce the amount of forest fuels that have built up for more than a century—the result of unbridled wildfire suppression and logging practices that have left forests primed to burn. But just who should decide how to do that has divided many in industry, government and science.

On one side, the timber sector says it should drive the solution; on the other, critics say it’s dangerous to allow an industry that helped spawn the problem direct its solution through their version of “forest management.”

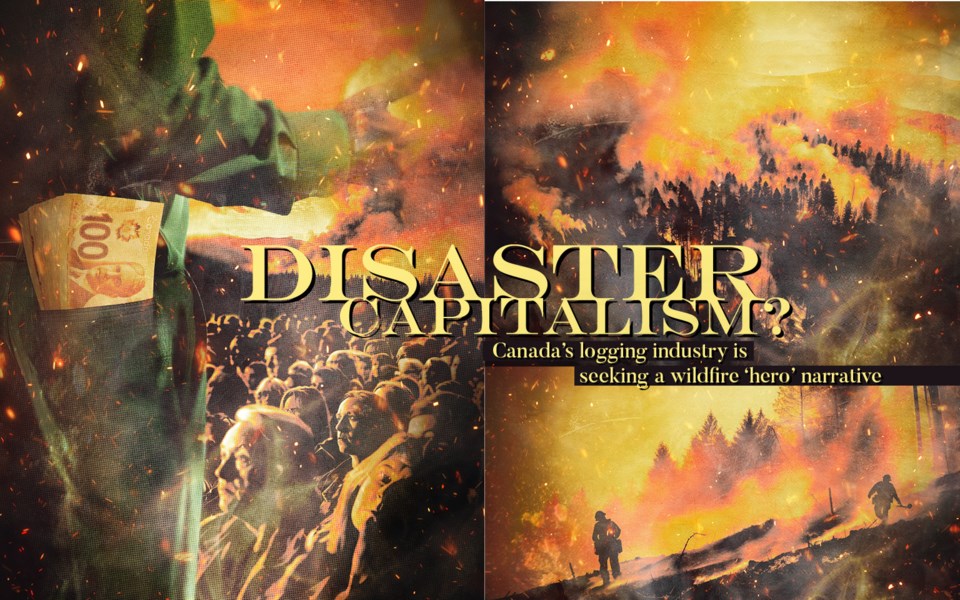

“It appears to be that they’re asking government and Canadians to write a blank check… It’s disaster capitalism—where industry takes advantage of a crisis to make money,” said Julee Boan, the Canada program project manager for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Boan said the record 2023 wildfires “really scared people” and left many looking for answers to a “wicked and complex problem” too big for any single sector to deal with.

“This is really complicated,” said Boan, who also has a PhD in forestry science. “They need to be part of this discussion on what to do. But they can’t be leading it.”

The disagreement hinges on what appears to be a simple question: does logging more reduce wildfires? Glacier Media asked seven experts in wildfires and forest ecology to help answer that question.

Karen Price, an old-growth ecologist who served as a technical advisor on B.C.’s Old Growth Strategic Review, said she now frequently hears the argument for logging to solve wildfires from people inside the Ministry of Forests.

She described the argument put forward at the COFI conference as “mendacious and dangerous” and that she has “seen no evidence to support logging to reduce wildfire risk in most of B.C.’s ecosystems.”

Price said thinning—removing small trees, leaving big ones and then burning understories—can reduce fire risk in some fire-dominated ecosystems. But in the thin-barked ecosystems that make up most of B.C., those practices would burn big trees.

“And even worse, where people have thinned in the name of ‘fuel reduction,’ they’ve taken the big trees and left small ones, removing old-growth values with no decrease in wildfire risk…” said Price.

‘Forest management’ far more nuanced than ‘logging’

Price pointed to evidence from B.C., collected in May 2023, when independent botanist and ecologist Paula Bartemucci carried out a field visit in a forest at Deception Lake outside the town of Smithers. The forest had earlier been deemed to have a “sufficiently high fuel hazard to warrant treatment.” A contractor was brought in to thin the forest and remove 15 tons of surface fuels per hectare, according to her report.

The forest there has spruce up to 200 years old and is classified as “big-treed old forests.” But after it was thinned, the forest “no longer had large, standing dead trees, large downed wood, large live trees, or abundant regeneration of various sizes,” wrote Bartemucci.

“The treated forest has lost old forest structure and function.”

Bartemucci later added that “the thinning treatment will likely make the site vulnerable to fire”—a result of increased drying, stronger winds, and lower relative humidity than before.

Price said that report is part of a body of evidence suggesting only fire-dominated forests of interior B.C. should be thinned and burned with low-intensity fires.

Most of the forest ecologists interviewed for this story agreed that limiting wildfires would require a combination of leaving moist forests unharvested, leaving burned forests unsalvaged, and encouraging the re-growth of more fire-resistant deciduous trees.

Lori Daniels, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Forestry, said the forestry industry would need to go through a transformative change if it wants to be part of the solution to wildfires.

“While it is true that fuels need to be reduced and reconfigured across many landscapes of interior B.C., forestry as it is currently practiced in B.C. contributes to the wildfire problem. So more of the same is deeply problematic,” said Daniels in an email.

Mathieu Bourbonnais, an assistant professor at UBC Okanagan’s Department of Earth, Environmental and Geographic Sciences, said if logging to reduce wildfires means more cutblocks and more conifer tree plantations of a single species “then it won’t help at all.”

Bourbonnais said mechanical thinning may use some of the same equipment as logging but generally involves removing fibre that is not profitable, such as small trees and saplings.

“They aren’t wrong in that we need to figure out ways to remove large amounts of hazardous fibre from many of our forests, but how to do that is far more nuanced than ‘logging.’ I hear this a lot but conflating logging with fuel treatments is a problem,” said Bourbonnais.

Evidence from U.S. shows limits of ‘forest management’

Forest ecologist Rachel Holt, who also served on B.C.’s Old Growth Technical Advisory Panel, said for forest management to actually reduce wildfires, it needs to focus on feeding value-added mills with small bits of wood—not chipping logs to feed the pellet industry and not exporting barely processed timber.

When Holt hears the words “forest management” she says it’s never clear what vision is actually being talked about. Rarely, she said, is there a recognition that to be successful, forest management will require cutting fewer trees.

“I hear the same words, but they don’t mean the same thing,” she said. “They are talking about sanitizing the forest of its biodiversity values—i.e. its old trees, its dead trees. They are talking about creating an agricultural forest.”

One 2022 study looking at thinning practices across the American West found “active management” led to widespread logging of fire-resistant live trees and snags. Degradation of wildlife habitat was “functionally equivalent to clear-cutting the forest understorey” in many cases leading to “weed-infested woodlands or savannahs that look nothing like the original forest.”

High-severity wildfire, found the study, is “substantially underestimated in thinned areas.”

Dominick DellaSala, who led the study as the chief scientist at Oregon’s Wild Heritage, said he is now working on studies across southeast Australia, the western U.S. and Canada that suggest previously harvested young forests “prime the fire pump” and burn hotter than old forests. In each region, he said logging has replaced old forests with slash and densely packed trees grown on a plantation model.

“And everyone knows when you start a fire, you start with kindling, small material, not the gigantic trees that you get in an old-growth forest,” he said.

DellaSala, who has been testifying about the effects of logging before the U.S. Congress since the 1990s, said in recent years, the U.S. timber industry has ramped up a lobbying campaign that frames wildfire as a solution only they can fix. The evidence suggests the “complete opposite” of what the timber industry is saying, with “messaging is akin to tobacco-cancer denialism and climate change denialism.”

“Right out of those playbooks,” DellaSala said.

A 2020 joint investigation involving the Oregon Public Broadcasting, The Oregonian/Oregon Live, and ProPublica uncovered documents that showed the timber industry aimed “to frame logging as the alternative to catastrophic wildfires through advertising, legislative lobbying and attempts to undermine research that has shown forests burn more severely under industrial management.”

In one 2019 presentation to the Oregon House Committee On Natural Resources, Chris Edwards of the Oregon Forest Industries Council showed a slide of a timber-framed building next to a young child with an oxygen mask.

“Where would you rather store carbon?” it reads. “Here? Or here?”

A national campaign to show ‘Canadian Forestry Can Save the World’

In Canada, using wildfires to influence public opinion appears to only just be taking off. Holt, who was shown statements made at the convention, said it was the first time she heard B.C.’s forest industry explicitly planning to frame itself as heroes ready to solve wildfires. She said she was shocked by the open conversation on how to influence public opinion and government.

But a closer look at forestry industry groups across Canada shows B.C. is not the only province where such a public narrative is taking shape.

Many of the largest forestry companies operating in Canada count themselves as members of multiple industry groups. Paper Excellence, West Fraser and Weyerhaeuser are all members of both the B.C.-based COFI and the Forests Products Association of Canada (FPAC).

According to Meta’s Ad Library, FPAC has spent thousands of dollars and reached millions of people on is “Forestry for the Future” campaign. The ads frame industry as players reducing wildfire risk as early as 2022. In one advertisement shared across Facebook and Instagram, the national industry group tells people to “take action” by emailing “your MP to support the policies that will improve forest conditions and keep communities safe.”

It goes on: “We can help mitigate wildfire risk through responsible forestry.”

On June 8, 2023, near the height of the 2023 wildfire season, FPAC’s president and CEO Derek Nighbor presented a blueprint for the campaign in a presentation to the Maritime Lumber Bureau in Saint John, N.B.

“Persuasion and opinion change are not something that happen overnight. Retention of information requires multi-platform saturation, memorable executions, and consistency of message to seed the underlying facts,” reads one slide.

The presentation, first reported by the Halifax Examiner, then lists a number of campaign activities—on transit shelters, at airports, through a “Capturing Carbon” documentary and through its “Canadian Forestry Can Save the World” podcast.

Other activities include TikTok and Instagram influencer partnerships, Indigenous partnerships and cross-platform digital advertising. By June 2023, the public influencing campaign had already reached 13.1 million Canadians—more than a quarter of the country’s population.

The presentation ends with a three- to five-year plan in which FPAC looks to expand its reach and appeal “to drive policy change and the sector’s place as a critical part of a growing, green economy.”

Glacier Media asked David Coletto what role Abacus Data had in shaping FPAC’s Forestry for the Future campaign, and who came up with the idea for COFI to use wildfire as a way to turn the forest industry into the ‘hero.’

Coletto declined to comment.

Familiar tactics from the same PR firms

Melissa Aronczyk has spent years tracking the PR strategies corporations and politicians use to reshape the narrative around environmental problems. A professor of media studies at Rutgers University, Aronczyk said FPAC and COFI’s public messaging are all well-known tactics.

“They are sometimes used in crisis situations, but more often these tactics are part of a long-term strategy to change the narrative around the industry to appear less environmentally destructive. This is a common playbook that gets opened up time and time again,” she said.

What’s remarkable about the playbook, Aronczyk said, is that it’s been around since at least the 1990s, an indication they are effective in influencing both the public and politicians.

Like COFI, documents show FPAC has also leaned on market research from Abacus Data to frame its Forestry for the Future campaign. Founded in 2010, the market research firm was formally chaired by Bruce Anderson, who worked alongside Coletto while leading accounts for the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and the Canadian Energy Pipelines Association, among others, according the website of his current PR firm spark*advocacy.

Anderson was also the founding partner of the Earnscliffe Strategy Group back in the 1990s, a firm that more recently has carried out lobbying for Pathways Alliance, a coalition of six fossil fuel companies that together account for 95 per cent of Canada’s oil sands production.

Aronczyk learned of the connections in a recent peer-reviewed study she carried out with two colleagues from Carleton University and the University of Ottawa. The research, published earlier this month, found the coalition had engaged in several examples of greenwashing—including producing non-credible claims to the public and selectively disclosing and omitting information.

Aronczyk said public relations firms are “notorious for their coordination and communication across industry sectors,” and often share resources and strategies through industry coalitions.

She said Abacus’s latest work for Canada’s forestry industry appears to be carrying on that tradition.