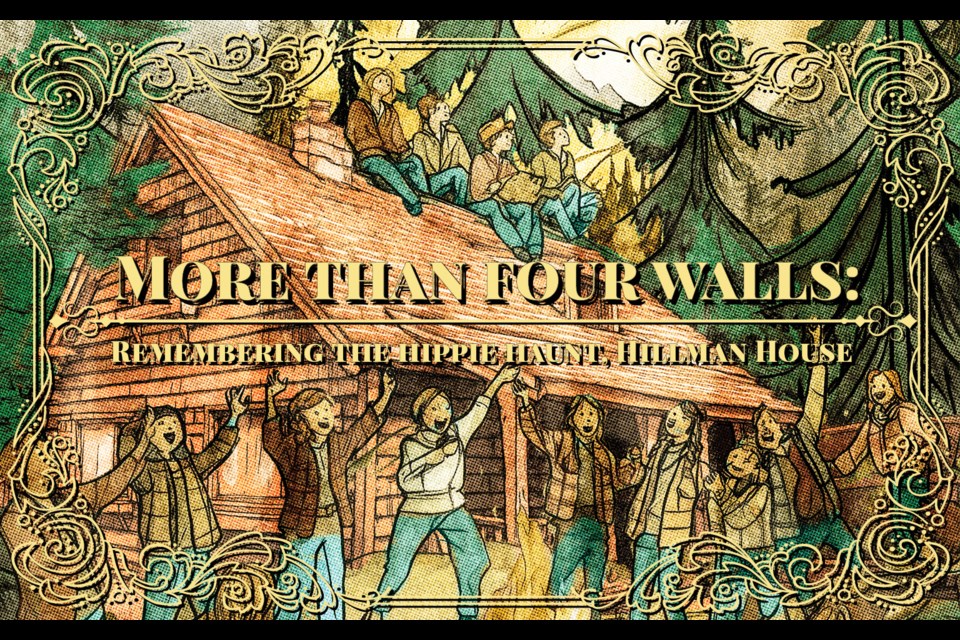

Hillman House, the historic home on the shores of Nita Lake, is significant due to sheer age alone. Built in the mid-1940s by lumberman Alf Gebhart, the Bavarian-style home ranks among Whistler’s oldest standing buildings.

But numbers alone don’t do it justice.

“That particular structure is unique in that it has connections to the logging industry, skiing, second homeowners and employee housing, as well as Whistler’s counterculture of the ’60s and ’70s,” said Brad Nichols, executive director of the Whistler Museum. “There’s not a single story that goes with that building, there are many stories.”

If its wood walls could talk, Hillman House would surely have no shortage of stories to tell. Over the course of eight decades, it has witnessed the community’s transformation from a cluster of summer homes and forestry operations to the modern mecca of ski tourism it is today, with threads connecting to each era of Whistler’s unlikely evolution.

On the eve of its demolition, Pique looks back at one of the community’s most historically significant buildings, as well as the challenge of preserving the past in a young and transient ski town addicted to constant progress.

The Gebhart Years

In 1936, Gebhart and his wife Bessie purchased a sawmill and lumber camp from a retired Indian army officer. Almost a decade later, after Gebhart had relocated the mill from 32 Mile Creek to the southeast end of Alta Lake, he eyed a patch of land near Nita Lake for his retirement home. Enlisting a Scottish mason who built the thick stone basement “substantial enough to hold a castle,” remembered former tenant John Hetherington, Gebhart used lumber from his mill for the walls and siding, and leftover sawdust for insulation.

Fine in the summer months when Alta Lake’s tiny population reached its zenith, the cabin proved difficult to warm up in the winter.

“To heat the place, it’d have needed to hold the sun,” Hetherington joked in a 2015 Pique interview.

Although Bessie was certainly not enamoured with the cold, dark cabin, the Gebharts stayed there until the sawmill’s closure, before leaving it to their son, railway worker Howard and his wife Betty. In the early ’60s, the house was sold to Vancouver schoolteacher Charles Hillman, precipitating its most infamous era as a popular flophouse for the town’s ski bums, hippies and burners; also when it earned its moniker as the original Toad Hall.

No, not that Toad Hall

Hillman was a man who defied easy categorization. Growing up in the woods of Ontario, he was a skilled outdoorsman, learning how to fish, hunt and skin rabbits, and helping his father build cabins in Muskoka cottage country. An accomplished educator, he oversaw a one-room schoolhouse in Glen Orchard packed with 48 students from Grades 1 to 12. Described by friends as a debonair, James Bond-like socialite, Hillman was the understated gentleman who could win over a crowd (especially the ladies) with his musical abilities and array of smooth-as-butter dance moves, which would serve him well on the ski slopes, too.

“He walked with [Fred] Astaire’s style—one foot directly in front of the other—and he skied like Stein Eriksen, the world’s most graceful skier, with Charles a close second,” wrote longtime friend, Dr. Ted Hunt, in honour of what would have been Hillman’s 100th birthday in 2017. “It was spellbinding to watch him on a wide track—such as Olympic Run—cutting long, sweeping turns in perfect form, with a vapour trail of powder snow blowing behind him.”

They were skills that would lend well to Hillman’s moonlighting as one of Whistler Mountain’s original ski instructors when it first opened for business in 1966. It was around that time that Bill Rendell and a couple friends discovered the seemingly abandoned cabin, kicking out the packrats and moving in. (They couldn’t keep the packrats away for long: Hetherington remembers having to regularly hide his socks, which the rodents loved to shred and use for their nests.) A draughtsman by trade, Rendell was responsible for crafting the instantly recognizable Toad Hall sign—named after Mr. Toad from the classic children’s novel, The Wind in the Willows—that hung over the cabin’s entrance until Hillman reclaimed the home for himself and (amicably) kicked out the ski bums, who took the sign with them to another popular squat.

Speaking to the home’s various iterations over the years, it goes by at least three different names: the Gebhart Cabin, Hillman House, and Toad Hall, the latter causing confusion to this day, with some people mixing it up with the Soo Valley property made famous by the iconic 1973 poster depicting 14 men and women in nothing but smiles and their ski boots, an image that has come to define Whistler’s heady hippie days, hanging on walls from Creekside to Kitzbühel.

Hetherington moved into Hillman House in late 1967 with three fellow 20-somethings: Jim Burgess, Drew Tait and Mike Wisnicki. Though they were the cabin’s official rent-paying tenants, they had a hard time convincing the steady stream of ski bums squatting there of that salient point. With a shortage of housing around town—plus ça change—it wasn’t unusual for Hetherington to wake up in the mornings, only to find a bunch of strangers crashing anywhere there was space, chicken coop included.

“Because I was the smallest guy, I was appointed the person to kick them out,” Hetherington recalled.

Long before online housing forums, word travelled far and wide about Whistler’s original Toad Hall, with random guests showing up unannounced under the belief they would be welcomed with open arms—which they were, at least for the night.

“One night and you’re out, that was our policy,” Hetherington said.

The rare times the drafty cabin would warm up was when the boys hosted one of their legendary house parties, which Hetherington said could attract up to 150 people, making up the lion’s share of the town’s population at the time. (Population figures from Whistler’s pre-incorporation days are estimates. The community’s first official census, in 1976, counted 531 residents.)

“Drew had bought a stereo system about the size of a small suitcase, and we’d get that going. We’d have music and invite whoever wanted to come along,” Hetherington said. “Lots of people would show up in various ways. The house would get warm from all the people and the activities and the fires. It was the only time the place would ever get warm.”

Eventually, Hillman wanted to reclaim possession of his cabin, and with police from Squamish in tow, he entered with a court order for the squatters to leave. (None of the prior tenants still lived there.) But not before granting them an extension so they could throw one last party.

Hillman used the property as his secondary residence in the ’70s, restoring some of its original design.

After its time as what the Whistler Museum called “a focal point of the growing counterculture in Whistler,” the home was eventually returned to the rental pool. Hetherington, who lived at Hillman House off and on over the course of three years, got to visit the home with his daughter in 2019, when it was still being rented.

“The building has been pretty much continuously used for a long time,” he said. “It’s really quite changed since I lived there. It had an electric stove, and a lot of other changes had happened.”

Ironically enough, the building’s tenants were unaware of the cabin’s long and storied history.

‘There needs to be a bigger conversation about heritage preservation’

In September, Whistler’s mayor and council got a look at a staff report assessing the current state of the Hillman House, as developers continued work on a mixed-use housing project on the site at 5298 Alta Lake Road.

In short, the building was in rough shape. Parts of the siding had rotted, ankle-deep water had flooded the basement, and the interior—save for a lonely dryer machine—had been completely gutted after asbestos was found. It was, quite literally, a shell of its former self.

Owned by the developer, the Michael Hutchison-led Empire Development Co., the building was supposed to be transferred to the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) and placed in a public park nearby on the same lot as part of the project’s approval conditions, with a deadline of January 2025 for

its relocation.

But with an estimated price tag of $415,000—costs that would at least partially be covered by the developer—to relocate the cabin, restore it and bring the interior up to code for, at minimum, seasonal use, officials decided against its preservation.

“Is there anything in this building that is unique and salvageable?” asked Councillor Jeff Murl at the Sept. 24 committee of the whole meeting. “I think the best part we’ve been able to preserve is the location … Having a building that’s not functional, that was pieced together quite quickly at the time is not something I’m as interested in.”

The decision came after much consternation from officials, who debated a variety of options to at least partially maintain the cabin, including moving the exterior shell to Rainbow Park, where several small, historic cabins dating back to the 1920s now sit.

Coun. Jessie Morden seemed to wrestle the most with the decision, mentioning her mother, former Mayor Nancy Wilhelm-Morden, and her past as a squatter in 1970s Whistler. Initially voting against the building’s demolition at the September committee of the whole meeting, Morden reluctantly flipped her vote when it came back to council the following month, citing the high cost.

“I was going to speak against this … but given everything that you have presented tonight, I will support this recommendation, but very apprehensively,” she said to municipal staff at the Oct. 8 council meeting. “We’ve talked about a mock design of a potential new Creekside Village, and we talked about how we’d like to keep that old-school Whistler vibe there. And so that’s why I’m apprehensive to knock this building down, because I want to hang onto our heritage.”

Maureen Rickli, who lived next door to Hillman House for five years in the ’80s while working at the Tyrol Lodge, was initially dead-set against council’s decision to demolish the cabin. That is, until she ventured to the site in December hoping to get a last look at it and preserve some artifacts for posterity. (She took a brick, a window, and a horseshoe hanging on the wall, items she has donated to the Whistler Museum.)

“When I walked through it, it was a nightmare,” she said of the state of the cabin. “If you saw it, you wouldn’t want to put money into it either, because it’s just not feasible financially.”

Although the building will be demolished, council ultimately voted in favour of staff’s recommendation to provide a replacement amenity at the park onsite—officials discussed a picnic shelter using some of the wood from the original building—that would offer information and recognition of the cabin’s history and cultural significance. The developer will also provide a cash contribution, equal to the total estimated remaining cost of moving and repairing Hillman House, to the Recreation Works and Services Reserve that will be used for heritage preservation and improvement, including several historical buildings located at the current site of The Point Artist-Run Centre near Alta Lake.

While that contribution will surely go a long way towards protecting Whistler’s remaining historic sites—there are 14 other buildings in the Whistler Valley older than Hillman House that the municipality recently identified as worthy of further investment—it does beg the question: why wasn’t more done to preserve the original Toad Hall before it fell into disrepair?

There have been efforts over the years to catalogue Whistler’s heritage buildings, but no official heritage plan or avenue for heritage designation has ever been formalized. In 1993, Hillman House was included in a draft inventory of significant heritage sites in the resort that was developed by the municipality and community volunteers. The RMOW has no record of the report ever being received by council.

More recently, a summary of local heritage sites was in the works, a joint effort by the Whistler Museum and the RMOW, that was put on pause in the pandemic.

Nichols, the museum’s executive director, said he understands the “tough decision” officials had to make on Hillman House given the price tag to preserve it, “but it doesn’t make the sting any less.” He’s hopeful it will spark dialogue in the community.

“There needs to be a bigger conversation on heritage preservation, and a heritage plan related to that,” he said. “Throughout the past 30 years, there have been starts and stops of this almost coming about, but nothing has been formally drafted at this point. Hopefully that will push this forward and we’ll see some progress in that regard.”

History, and its preservation, is often an uphill battle, especially in a young, transient tourism community that, by its very design, is constantly looking ahead, to the next big amenity, the next shiny housing project, the next new lift upgrade.

“It’s fair to say our focus has been on housing and climate action. Any discretionary funds we’ve had have really been focused on growing our stock of employee housing,” said Mayor Jack Crompton. “This discussion of the Hillman cabin has raised heritage investments to a greater consciousness for council. Certainly, this is not something that can or should be ignored. The inventory staff has provided gives us a lot of insights moving forward.”

Admittedly, there are inherent barriers to this important work in Whistler, which makes it all the more essential to carve out the resources and political will to actually see it through. Asked how we do as a community when it comes to nurturing and sharing our history, Nichols took a day to mull over the question, one he has spent a long time thinking about in his career.

“A simple answer is that we’re doing quite well as a community when you think about how many visitors we get per year, how many folks follow and interact with us on social media, and how many people attend museum events,” he wrote in an email. “However, there’s also lots of room for Whistler folks to become more active participants in the process of preserving our history. The older generations are leading the charge on this by actively donating artifacts and offering to share stories of their experiences. We want the community to know that they can have a say in what becomes Whistler’s history by sharing their own stories, even of the very recent past, and even if (or especially if) their stories don’t fall into what we’d traditionally think of as ‘mountain culture.’ The Museum is actively working to collect stories about underrepresented experiences. We often forget that history is being made every day! We’re also exceptionally lucky as a community of our size to have an organization like the [Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre] that is doing the work of preserving their much longer history and ongoing culture.”