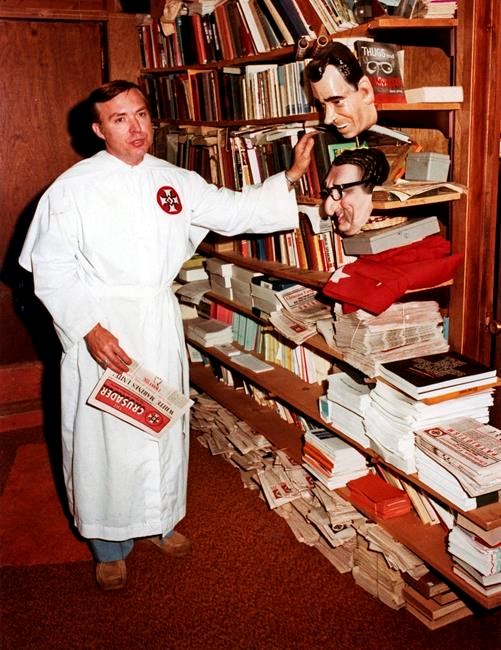

LOS ANGELES — Tom Metzger, the notorious former Ku Klux Klan leader who rose to prominence in the 1980s while promoting white separatism and stoking racial violence, has died at age 82.

Riverside County Department of Public Health spokesman Jose Arballo Jr. said Metzger died Nov. 4 at a skilled nursing facility in Hemet. The cause was Parkinson's disease, Arballo said Thursday.

The former grand dragon of the California chapter of the Ku Klux Klan became one of racism's most prominent figures after he left that organization in the 1980s to form the White Aryan Resistance movement.

He eventually was pushed into the shadows and financial ruin, however, for his organization’s role in the 1988 beating death of Ethiopian college student Mulugeta Seraw in Portland, Oregon.

Seraw's family won a $12.5 million judgment against Metzger, his organization and others in 1990 following a trial in which a recording was played of Metzger praising the killers for performing what he called their “civic duty.”

Metzger lost his San Diego-area home, his television repair business and other assets. Although left penniless, Metzger continued to produce a racist newsletter for years and operated a racist hotline, taking calls personally.

He posted regularly on his organization's

“Tom Metzger spent decades working against core American values as one of the most visible hardcore white supremacists in the country," Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan A. Greenblatt told The Associated Press. “Throughout his life, he engaged in a wide range of hateful activities from spreading anti-Semitic and racist rhetoric to launching vigilante border patrols as a California Klansman to recruiting skinheads to the white supremacist cause.”

The killing of Seraw left racial wounds in Portland that continue to this day, said Randy Blazak, a former sociology professor at Portland State University who has written extensively about hate groups.

“We became known as Skinhead City. We had racist skinheads and anti-racist skinheads doing battle in the streets, which is sort of a precursor of antifa and the Proud Boys,” he said, referencing those involved in recent violence that have gripped the city.

Born in Warsaw, Indiana, on April 9, 1938, Thomas Linton Metzger served in the Army from 1956 to 1959 before settling in California and a career as a TV repairman.

He joined the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in the mid-1970s, rising to the role of grand dragon of California before leaving to form the White Aryan Resistance in the early 1980s.

He ran for Congress from northern San Diego County in the early 1980s, winning the Democratic Party primary but losing by a landslide in the general election after Democrats and Republicans united against him.

He became a prominent media figure during those years, appearing on TV talk shows, organizing white supremacist demonstrations and cross burnings and promising a white civil war that would result in “blood in the streets.”

His son, John Metzger, and other white racists appeared on Geraldo Rivera's TV talk show in 1988 and brawled with Roy Innis and other Black civil rights activists. Rivera suffered a broken nose during the televised mayhem, which created a national furor.

Tom Metzger's downfall began after he sent one of his White Aryan Resistance members to Oregon to organize a local Nazi skinhead group. Within a month, local skinheads had beaten to death the 28-year-old Seraw with a baseball bat. They later admitted they singled him out because he was Black.

The civil judgment stemming from the killing was devastating for Metzger, said Elden Rosenthal, one of the attorneys who represented the Seraw family.

“We chased him for 20 years. We collected money from him for 20 years, which is the limit under Oregon law," Rosenthal said. “The goal of the case was to put him out of business and to impact his standing in the white supremacy movement — and we thought we accomplished both of those things.”

Another attorney, James McElroy of San Diego, arranged the sale of Metzger's house to a Latino family to help satisfy the judgment.

“Poetic justice,” said McElroy, who went on to adopt Seraw's son, who was 7 when his father was killed. The boy is now in his mid-30s, is married and works as a pilot for a major airline, the attorney said.

Although Metzger has long been identified as a white supremacist, he actually shunned that term, saying he was a white separatist and didn't have a problem with Blacks who did not interact with whites.

Still, the racial hatred he fomented continues to this day, McElroy and Rosenthal said.

“At the time, I looked at him as totally on the fringe,” Rosenthal said. “What we have unfortunately learned over the last 30 years is that there’s a whole lot of people who share his views. … At the time it seemed fringy, now it seems a bit frightening.”

___

Associated Press Writers Gillian Flaccus in Portland, Oregon, and Elliot Spagat in San Diego contributed to this story.

John Rogers, The Associated Press