Nearly a decade after moving into his Cheakamus Crossing home, Tony Routley feels a palpable sense of relief. That's because, for the first time, his home is being heated by a standard electric boiler, not the controversial ambient heating system known as the District Energy System (DES) that was installed in the former Athlete's Village as part of the "greenest Olympics ever."

"It's a relief," said Routley, who eventually spearheaded the issue as the volunteer appointee to Cheakamus Crossing's DES Committee. "When it was all in and done, it was like, 'Oh, Jesus, I feel like a bit of a weight's been lifted.'"

That solace is understandable given the headaches Routley and some of his fellow Cheakamus residents have dealt with in the years-long saga of the DES, which was touted by officials in the lead-up to the 2010 Winter Games as a sustainable, energy-efficient alternative to traditional heating that would cost them less on their monthly bills.

For many homeowners, that was exactly their experience, but for a not insignificant number of others, the DES, which extracts heat energy from treated wastewater, led to a litany of technical issues, steep repair costs, and the unease that comes with not knowing whether the heating will work on any given day.

"Prior to [the electric system] being installed, I was using my stove to heat my house, so the peace of mind that I feel is from the 15-year warranty and the credibility of the guys who installed it," said Whitewater resident Jody Wright. "There's not a lot of moving parts, there's not many variables to deal with. We had so many different companies that came in who said different things to us [about the DES], so it was this mysterious puzzle."

After years of lobbying and a handful of proposed solutions that were ultimately rejected by Cheakamus residents, the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) came back to the table last August with a proposal offering to pay every homeowner in the neighbourhood $5,000, provided 75 per cent of each respective strata signed on and agreed to waive the municipality of any future liability. Faced with the prospect of enduring another winter without reliable heating, not to mention the risk of absorbing future pricey repairs while living in resident-restricted housing (the vast majority of Cheakamus homes are part of Whistler Housing Authority [WHA] inventory), and the choice was clear: take the money and run.

"When you start adding up all of [the potential replacement costs], that was definitely alarming to me," explained Whitewater resident Mike Boehm. "The fact that the muni did whatever you want to call it, but they were willing to give $5,000 if we were willing to sign it and we wouldn't come back and sue them at any time down the road, I thought it was the perfect time to take that opportunity."

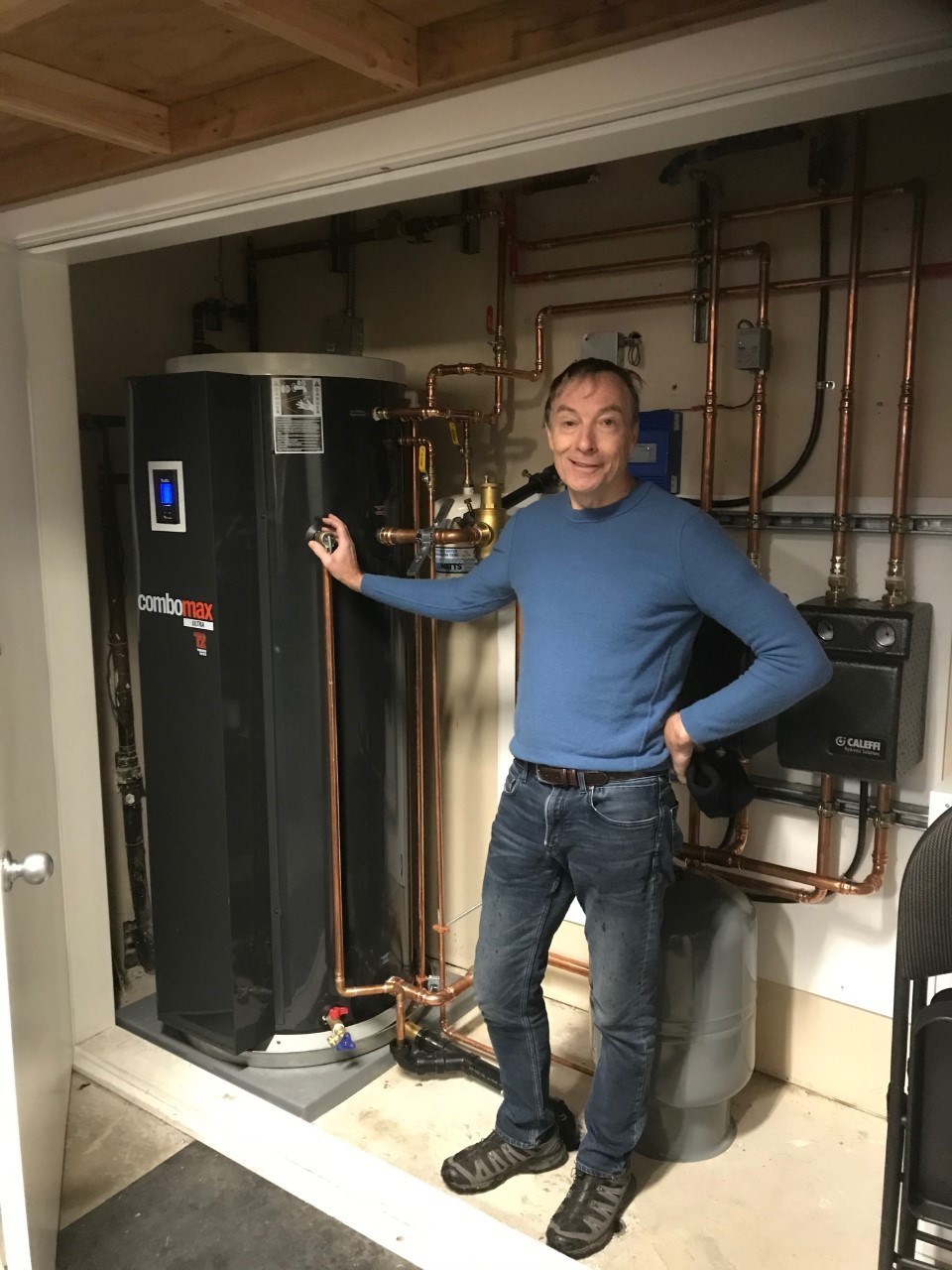

Pique spoke with four of the eight homeowners who have either disconnected or are in the process of disconnecting from the DES (with more expected in the coming months), and each acknowledged the $5,000 rebate, while a nice gesture, is still only a drop in the bucket compared to the repair costs they've already endured, as well as the $14,500 it cost them to install the Thermo2000 ComboMax Ultra electric boiler.

"The $5,000 didn't really solve the problem. It wasn't enough money," said Wright. "The reason why we accepted the money is because we just wanted to end it and move on. Dealing with the bureaucracy of the RMOW is just too lengthy, too political and they have more expensive lawyers at their disposal."

(A silver lining for residents is that, like any capital improvement to a WHA home, they can incorporate the cost of replacing their heating systems into the resale value of their residence.)

But more than a decade after it was installed, there is still little consensus as to what exactly led to the operational issues with the DES. A 2017 report commissioned by the Whistler 2020 Development Corporation, a municipal subsidiary that was responsible for developing the former Athlete's Village, stated that there does not "appear to be any widespread systemic issues with the DES or the individual home heating systems that are the result of installation or component failure," although technicians did note the initial cleaning and start-up of the systems at the time of installation "may have been lacking."

For Routley, who has had to verse himself in the inner workings of the complex heating system and its component parts, the root issues are twofold. "I think water quality was definitely an issue and the equipment they put in did not address the water quality," he said, noting that considerable amounts of sludge were removed from his original hot water tank when his new system was installed. "It made it so that the water became a problem, because the proper things weren't done to mitigate the water issue," like regularly flushing the system with distilled water.

Routley believes the rush to install the state-of-the-art system in time for the 2010 Olympics played a role in the systemic issues residents encountered.

"Absolutely, it 100 per cent played into it," he said. "If you had a crystal ball, I don't know if people had more time on the engineering side to figure things out, how it would have gone. Who knows? But there's no question it was rushed in. It was political. 'We're gonna be the greenest [Olympics] and we're going to slap this thing in' and other considerations weren't taken into account."

With two recent WHA builds, and another project on the horizon, new Cheakamus residents will have no choice but to join the DES. Boehm advised incoming homeowners to do their homework.

"Read your manual as closely as possible and understand that there's going to be annual maintenance required, there's just so many moving parts to it," he said. "If you try and come up with a budget to ensure that you're going to make your system run as effectively as possible, it works well. But just be prepared that the long-term costs on it are going to be there."

Wright's advice was even more pointed: "I would say make every effort not to be part of a system that does not work properly."