Whistler's cultural and artistic landscape is set to change forever when the doors of the Audain Art Museum open to the public March 12. More than 200 pieces of art from the personal collection of Vancouver developer and philanthropist Michael Audain and wife Yoshi Karasawa will be on display in their new $35-million-plus museum — a venue dedicated to the art of British Columbia from the 18th century to today, from a preeminent collection of early First Nations masks to internationally renowned photographers of today.

"Mr. Audain's collection really is a kind of a searching inventory of artists that have really strived to identify a spirit of place," says Canadian art critic Sarah Milroy. "And I think (Emily) Carr historically is the grandmother. Between her on the white colonial side, and someone like Jim Hart on the indigenous side, we get a sense of deep traditions of engagement with the landscape in British Columbia from different sides of the cultural divide."

In the weeks leading up to the museum's opening, Michael Audain sat down with

Pique. In this three-part series, Pique will look behind the scenes at some of the art, the man who has collected it, and the museum he has built in Whistler. We begin with the intrepid Emily Carr.There will be no gilt-edged golden frames for Michael Audain's Emily Carrs. No antique wooden borders, no ornate surrounds. All 24 Carrs have been stripped of any additional finery and are hanging in simple white frames, all the better to see Carr's vivid forests and striking totem poles, all the better to see B.C. through her wondering eyes.

Carr aficionados may be surprised, admits Michael Audain, of seeing the Emily Carr's like this.

"It's a new way of seeing Carr in a sense," says Audain, himself an aficionado, as he talks about Carr as one would a long-time friend, threading the stories of his collection with stories of Carrs life. "I think for people who are interested in Carr, I think they'll find it quite intriguing."

Audain has just walked through his gallery in Whistler where workers are in a race against time for the fast-approaching opening day. Back in his elegant Vancouver office, with False Creek glittering in the distance, the frenetic pace of activity two hours up the Sea to Sky corridor seems a million miles away as Audain transports us back through a history of Canada's preeminent female artist and his special relationship with her works of art over the last several decades. Emily Carr is not the most internationally renowned artist in his collection, and, arguably, she isn't the most significant. But taken as a whole, the two-dozen pieces, housed in a gallery of their own, make up one of the most important Emily Carr collections after the Vancouver Art Gallery and the National Art Gallery, and will only serve to fuel the fire that is Carr's rising popularity.

Audain bought his first Carr in the early 1970s. It was a "small French one" — Brittany Cottage, he thinks it was called. He paid $3,200 for it — far and away the most he had ever paid for a piece of art at the time, though he was already an avid collector.

"I guess it was an affirmation that I had an interest in Carr and I was prepared (to pay) what to me at the time seemed to be a very large sum of money," says Audain.

"It wasn't just the name. The picture attracted me. I knew it wasn't a classic Carr. It was an early Carr. But I thought it was the only way that I could start to acquire her work."

He had to sell that piece a few years later when he ran into financial difficulties. In the time he owned that small French painting, it doubled in value. He never bought it back. A much larger piece, like Audain's first Carr, however, will now hang in the museum — House with Slanted Roof — Brittany. This piece, as with Audain's first piece, shows Carr in her early years, just being exposed to post-Impressionism in Europe after spending some time training in France.

"It's very unusual for a woman artist from B.C. to be exposed to such advanced ideas, well, for any artist from B.C. to be able to be exposed to such advanced ideas in Europe and respond to it in such a sophisticated and intuitive way," says Milroy.

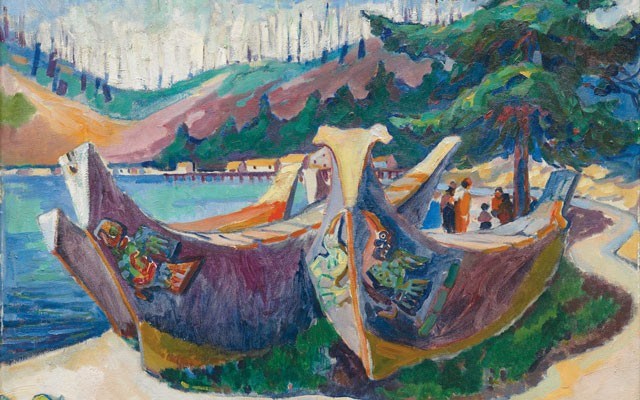

Carr, who was born in Canada in 1871, returned to Victoria after her time in Paris, and began to paint in earnest the world around her — the war canoes of Alert Bay (a painting that "would be the envy of any Canadian museum," says Milroy), the totem poles of Cape Mudge, the arbutus trees.

"I think Carr, uniquely for her period in time, understood that her view was an outsider's view and that she was looking into a world and to cultures that she didn't necessarily understand but was intrigued by," says Milroy, of Carr's relationship with First Nations and the British Columbian landscape.

An adventurer at heart, Carr threw herself into the deep end, soaking it all in, telling the story of B.C. through her brush. It's a story retold in Audain's gallery.

From the bucolic House with Slanted Roof to the dark and commanding work called The Crazy Stair, painted decades later, Carr's creative life is laid bare.

Audain bought The Crazy Stair, painted in 1928-30, for a record-breaking $3.39 million in 2013. It was the most ever paid for a Carr, the fourth highest price for a picture at auction in Canada. A commanding price for a commanding piece, it's bold and dark and Audain wanted it for the Whistler gallery.

Then come the pieces from her mature period — works like Gaiety and Forest — pieces, says Milroy, that are full of movement and real freedom and "an explosive, flowing, rapturous vision something akin to Walt Whitman's vision of nature."

"You really see all the different phases of her career in this collection, which is extraordinary to have all in one place at one time for viewers," Milroy adds from her home in Toronto.

Just recently, Milroy recalls opening the current issue of Tate Etc., Europe's largest art magazine, and there was Emily Carr.

"It's certainly the first time that I've ever seen Carr's work casually slipped into the continuum of international art history," says Milroy. "I opened my copy of the magazine and just about died; I was so excited because it was just so nonchalant but, of course, she belongs there. That certainly was not the case until the last 10 years or so."

Milroy was instrumental in the 2014/15 Carr exhibition in London at the Dulwich Picture Gallery. The successful run was followed by a version of the show at the Art Gallery of Ontario. A few years ago in 2012, seven of her pieces were included at dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, Germany, where Carr was introduced in a completely new context in Europe. The d'Orsay Museum in Paris will include her work in a 2017 exhibition.

"I think it's about time," chuckles Audain.

"I maintain, and I've maintained for a long time, that if she lived in Paris... and gone out to the rainforest on the West Coast of Canada and come back with a bunch of sketches that she could work up in studio, if she then showed them in Paris, she would have been taken up — she would have been very celebrated... She would have been amongst the world's most illustrious artists."

One aspect of great art, says Audain, is uniqueness, and Carr's work is unique. It isn't just the scenes and the content, the First Nations themes early on, but also the way she came to grips with the landscape later in life.

"I think she's one of the great painters of forest and trees in the world and she captured the beauty and mystery of west coast rainforest in a way that no one did before or since," says Audain.

"Emily's star hasn't waned yet. She is ascending into the sky. There's going to be a lot more notice taken in the art world in the future of this very distinguished painter.

"There's more in store for Emily Carr."

Indeed. And Whistler will be forever part of Carr's stratosphere from its new museum in the forest.

Next week look for Part II of the Audain Art Museum series — Beyond Emily Carr