As Shane "Tuna" Bell leads a small group of travellers through centuries-old woods thick with cypress, cedar, Sitka spruce, and black alder in Haida Gwaii, the serene waters of Security Inlet lapping the shore, he encourages us to take off our shoes and socks. We're walking on a mossy forest floor, and feeling our feet gently press into the soft ground is one way to connect with the land—physically and spiritually.

Bell, whose Haida name is Gyaagan Sgwaansang (meaning "one and only"), and whose childhood nickname never left him, is a cultural interpreter with Ocean House Lodge at Stads K'uns GawGa (Peel Inlet). It's a new cultural eco-tourism resort operated by Haida Enterprise Corporation (HaiCo).

A member of the Eagle clan, the 25-year-old Bell and fellow guide Jaylene Shelford, 19, point out huckleberries and salal, hemlock and devil's club, liquorice fern and stinging nettle, mushrooms ("bears' cookies") and more, all of which their ancestors used in various forms to survive prior to colonization.

Also in this grove lush with ferns are culturally modified trees—those that have been visibly altered by Indigenous people as part of their traditional use of the forest. The towering red cedar we're looking at appears to have had a slender section of bark stripped away, possibly with tools made of stone, bone, or shells to make baskets, mats, or clothes.

The Haida took only what they needed, knowing that everything in nature, including humans, is interdependent, with respect and reverence for the land being one of their enduring principles.

For Bell, the land that his people have called home for millennia is the greatest place on the Earth.

"I love the abundance of food the Mother Land provides for us," Bell says. "I love being immersed in our culture. I love constantly learning more about my own culture and properly educating other people about our culture. I love being close to my family; I know the village where my ancestors came from; it's called Kiusta at the northern end of Haida Gwaii. It was where one of the first contacts happened.

"We are doing what we can to preserve our nation, to preserve our language, to preserve our culture," he adds. "We're a living culture—it's very much alive."

Culture is the central focus at Ocean House, a 12-room fly-in floating lodge that's anchored off the rugged and unspoiled west coast of Haida Gwaii on Moresby Island. HaiCo renovated the former fishing lodge following the 2012 opening of Haida House, a land-based eco-lodge in Tlell on the east coast of Graham Island. (It also operates fishing lodges and Haida Wild Seafoods.)

Facing Mount Morseby, where trees seem to stand tall in every shade of green, from emerald to eucalyptus, Ocean House is accessed via a 12-minute helicopter ride from Sandspit. The lodge has luxuries like a spa, steam room, and hand-carved cedar sauna with a picture window that lets you gaze out at forests and sea while you warm up; bar service with cocktails (including kelp Caesars) and B.C. wines; and an elegant but comfy communal living space (complete with throw blankets you can take to the adjoining covered deck to watch hummingbirds, herons, and stars). There are paddleboards and kayaks for guests' use and a library with board games and books about Haida language, artists, and history.

What makes a visit to this remote place so memorable (besides the jaw-droppingly beautiful scenery), however, is the sharing of Indigenous culture. Through songs, stories, art, and food, along guided walks or sea-faring excursions (during which you might see eagles, seals, sea lions, bears, deer, puffins, or whales), you're immersed in so much legend, tradition, and knowledge.

Shelford, who was gifted her great grandmother's drum made of elk hide, was born with a voice that's astonishingly apt given that her Haida name, Daatsii, means "songbird." To the steady beat of that drum, she sings a song in the Haida language as 12 travellers ply the water in a one-tonne canoe made of red cedar using paddles carved of yellow cedar by Gitkinjuaas, Hereditary Chief Ron Wilson. During the winter, that canoe is housed in the Haida Heritage Centre at ay Llnagaay in Skidegate.

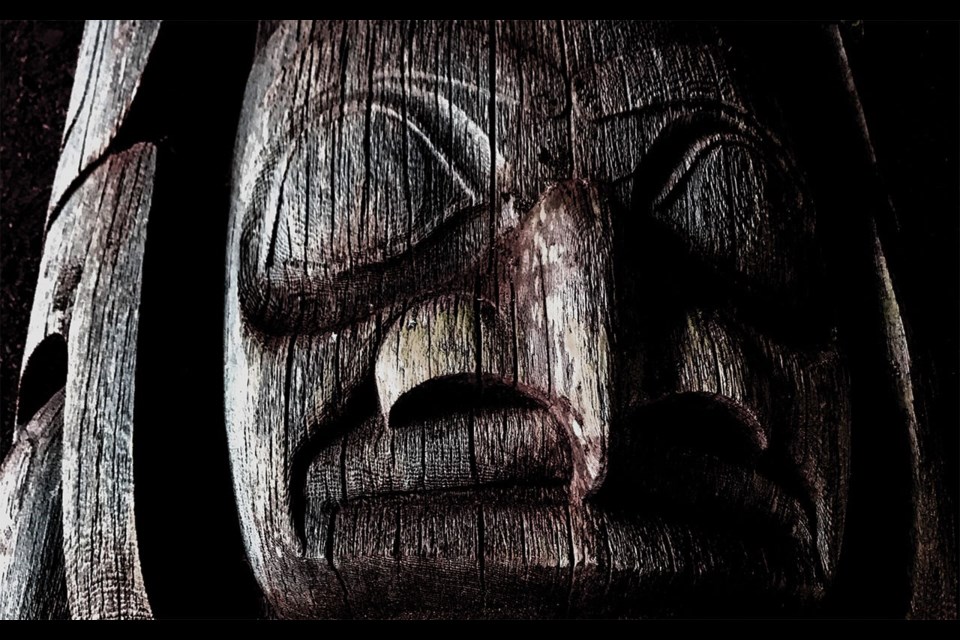

In the ancient village of Kaysuun, where cedar longhouses fronted by poles declaring a clan's animal symbols (totems) once stood, there are clues to a once-thriving community: cedar beams and the remains of a foundation, now shrouded in moss, sinking back into the earth. Before we approach the village that was abandoned in the 1880s, Shelford sings a berry-picking song to let any nearby bears know we mean no harm.

In the artist's studio, Gladys Vandal weaves Haida hats—one of which has been commissioned by the National Gallery of Canada—out of strips of aromatic cedar bark that she has soaked in water. A grandmother, Eagle clan member, and participant of the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program (which helps ensure the language is here to stay), she's one of the lodge's artists-in-residence, who rotate weekly.

In the kitchen, Old Massett-born chef Brodie Swanson, a member of the Raven clan, keeps his culture alive by serving items such as fresh razor clams, crab, and salmon with ingredients like seaweed, sea asparagus, "chicken of the woods" (a wild mushroom), and squid ink.

On the final night of a three- or four-night stay, when staff members don traditional Haida regalia in bold red and black, hotel guests join at a long table to share in a family-style potlach.

The name Haida Gwaii translates to Islands of the People, and it's the people who are keeping this culture alive who will stay with you.

Access:

I visited Ocean House as a guest along with other freelance journalists. The flight from Vancouver to Sandspit is approximately 70 minutes aboard North Cariboo Air; from there, guests board a Helijet to Peel Inlet. Three-night packages, $4,410, include return flights from Vancouver; guided zodiac, boat, and walking tours and wildlife viewing with cultural interpreters; 24-hour kayak, paddleboard, steam room, and sauna use; and all meals, snacks, and wine with dinner.