From the moment Canadian sculptor Mark Prent hit the art scene, his works tapped into the dark corners of the public imagination.

In 1972, people lined up outside the Isaacs Gallery in Toronto to see why everyone was so worked up about a solo show by an unknown artist in his mid-20s.

Inside, they found a gory scene: an artistic buffet of human body parts splayed across a butcher's counter.

In response to a complaint from a purported public morality watchdog, Toronto police tried to shut down the installation, laying charges for the public display of a "disgusting object."

A successful legal battle in defence of the gallery and artist launched Prent's career as a trailblazer of the dark arts.

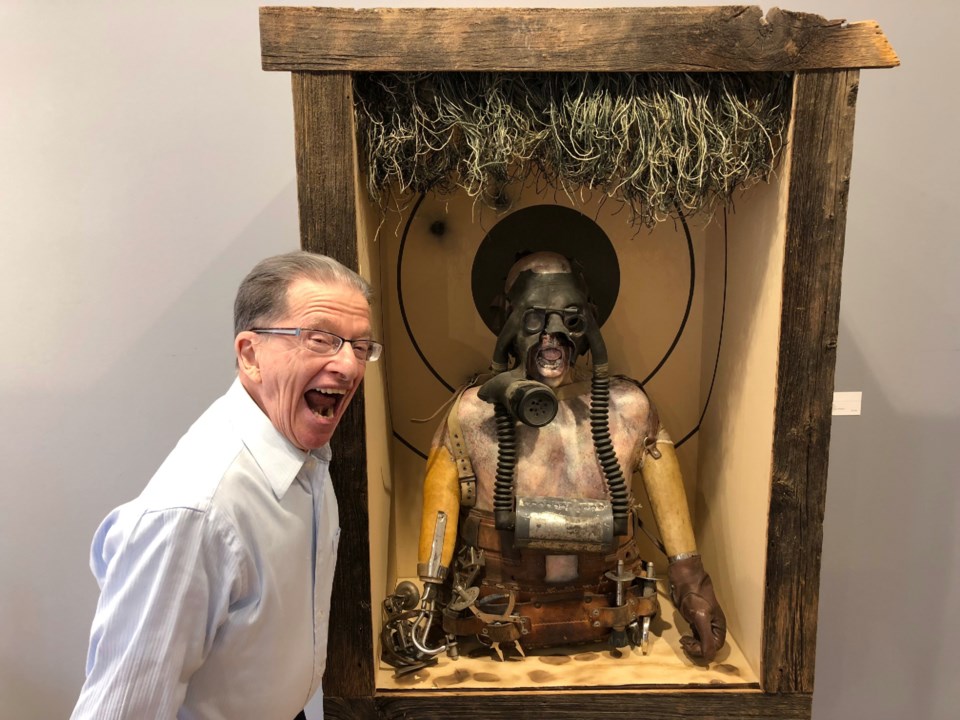

Depending on your perspective, his creature-like creations come across as incarnations of a dream, or your worst nightmare.

But Prent's wife says the artist, who died last week, saw his work as a form of "extended realism."

"It was so real, but at the same time, it was fantastic," Sue Prent said by phone. "It wasn't really realism. But you believed it was alive."

Sue Prent said her husband died of an aortic aneurysm at a Vermont hospital on Sept. 2. He was 72.

Born in Lodz, Poland, in 1947, Mark Prent immigrated to Canada with his parents as an infant and settled down in Montreal.

As a young artist at Concordia University, Prent developed new techniques to imbue his otherworldly sculptures with visceral verisimilitude. For example, Sue Prent said he developed a method of "reverse painting" involving gradations of coloured coats to recreate the translucency of flesh.

Like a figurative Dr. Frankenstein, Prent's pieces often stitched together an array of anatomical horrors — screaming faces, exposed innards, multi-limbed mutations and forms so unsettling they seem to defy description.

The cognoscenti of the art world embraced Prent as a visionary of grotesquery, doling out honours including 17 Canada Council grants and a Guggenheim Fellowship, and exhibiting his works across the globe.

Collectors in the art market, however, were initially not as enchanted with Prent's monstrous whimsicality.

"All those years he worked, he never changed his style. It didn't matter if it doesn't sell," said Toronto gallerist Phillip Gevik. "Not a lot of people were interested because of the subject matter."

But Prent's surreal sensibility earned him a few notable fans in the film scene. His pieces have appeared in exhibitions curated by directors Guillermo del Toro, David Cronenberg and Harmony Korine.

"His work was very cinematic," Sue Prent said. "He always used to say he would like to do film, because he felt like that was a medium he would be well suited to."

After a short stint in Germany, Prent and his family settled down in Vermont in the early 1980s, so they could afford more space for a home studio, his wife said. He split his time between there and Montreal so he could teach at his alma mater, Concordia.

For all his notoriety as a preternatural provocateur, Sue Prent said her husband was a jovial personality.

His goal was never to disturb, she said, but to intrigue.

"His work did not spring from preconceived ideas ... The narratives grew out of the process. It was like a mystery tour," she said.

"They basically came out of a dream world. And I think they just reach people very viscerally."

Prent leaves behind his wife and their son, Jesse.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 11, 2020.

Adina Bresge, The Canadian Press

Note to readers: This is a corrected story. A previous version said Prent's first solo show at the Isaacs Gallery was in 1973. In fact, it was in 1972.