Athletes across North America forced the conversation around police injustice in a monumental way last month when they refused to play following the shooting of Black man Jacob Blake at the hands of Kenosha, Wis. police.

What made the move—led by the majority Black leagues of the WNBA and NBA—so impactful was the scope and profile of the protests. Sparked by the Milwaukee Bucks, NBA players were in the midst of the playoffs, naturally the highest rated and most profitable segment of the season for the billionaire owners and multi-billion-dollar TV networks showing the games (even with no crowds in the NBA’s Disney World bubble and the pandemic-induced drop in ratings that has affected all sports).

It’s not hyperbole to call the strike one of the most significant political statements in professional sports of the last 50 years, not only because of the widespread dialogue it has sparked on both sides of the political spectrum, but because of what the players got back in return.

After consulting with former U.S. president Barack Obama, LeBron James and the players’ association made a list of demands to the NBA before they were willing to return to the court. Probably the most significant of these was that each franchise-owned stadium be converted into a voting location for the 2020 U.S. election, no doubt a blow to President Donald Trump’s not-so-subtle efforts to supress votes in largely Democratic urban centres by systematically dismantling the U.S. Postal Service and actively discouraging mail-in ballots in the midst of a pandemic. (Although Trump had no problem urging voters last week in the historically Republican-dominated state of North Carolina to vote twice—once in person, and once by mail—despite its obvious illegality.)

Of course, some media commentators framed the mass player walkouts as nothing but an exercise in awareness-raising, which conveniently ignores the genuine change the NBA’s workers have managed to achieve.

Others in the mulish “stick-to-sports” crowd have predictably chastised the players as spoiled, overpaid divas. It’s the same wilful ignorance that reared its ugly head four years ago when San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick began kneeling during the national anthem in protest of police brutality, and one that Trump’s dead-eyed Nepotist-in-Residence Jared Kushner put so succinctly when he told a CNBC reporter that NBA players have “the financial luxury” of taking a night off work that most Americans don’t, ignoring the fact that millions of Americans of varying socioeconomic status have already taken to the streets to protest police violence and Kushner’s own administration right alongside these athletes.

There’s something disturbing about a largely white sports media industry and an overwhelmingly white league ownership structure demanding the players they rely on to line their pockets to just shut up and stick to what they do best: hucking a ball through a hoop. It reinforces a sense of ownership over Black and brown bodies that has existed since slavery by telling them they are only as useful as the physical feats they are capable of.

And while these most recent protests made history because of the attention and impact they’ve garnered, athletes have been speaking out against injustice for decades.

In 1961, NBA star Bill Russell and his Black teammates were denied service at a Kentucky hotel restaurant, which led them to boycotting a scheduled exhibition game. Unsurprisingly, the protest didn’t get much attention in the papers, but you can draw a direct line from Russell’s action to the NBA players of today, who the Boston Celtics legend has commended for standing up for what they believe in.

In 1968, Black track stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos created one of the most indelible images in Olympic history when they raised their fists in a Black Power salute during the medal ceremony at the Mexico City games.

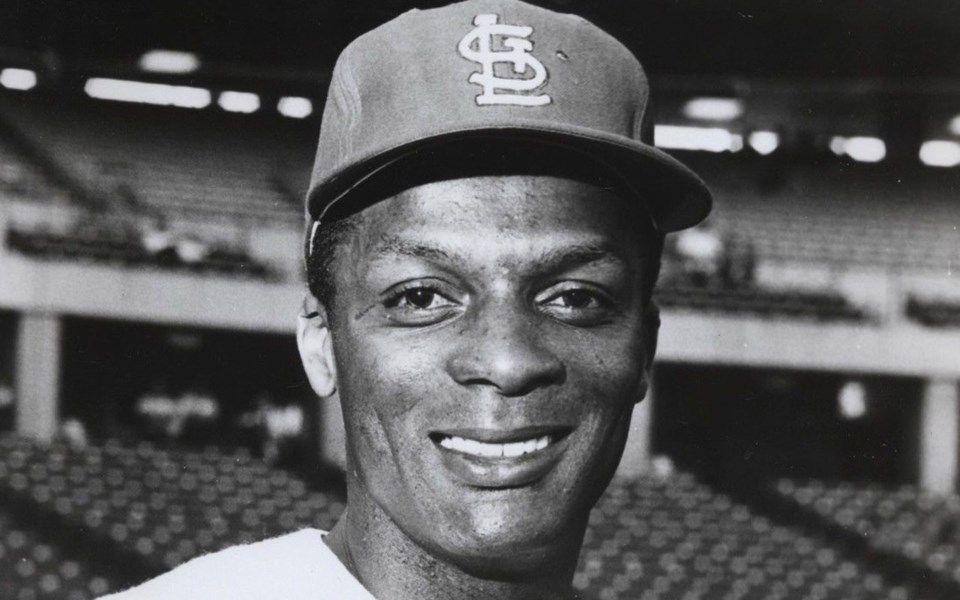

The following year, St. Louis Cardinals’ centrefielder Curt Flood became one of the most pivotal figures in sports labour history when he refused to accept a trade to the Pittsburgh Pirates, raising issue with the MLB’s outdated and draconian reserve clause, which kept players beholden for life to the franchise they originally signed with, even after they had satisfied the terms of their contract. After leading the charge for free agency in baseball, which other sports leagues have since adopted, Flood was unsurprisingly criticized for his outspokenness, saying that ballplayers were wealthy and therefore shouldn’t complain about their contract conditions.

Flood responded with a memorable remark that could just as easily have been uttered by one of today’s socially conscious pro athletes: “A well-paid slave is nonetheless a slave.”