When I was young and irresponsible, I made my way to Greece with a good friend and no particular goal in mind other than to enjoy some kind of a summer vacation after spending the past five of them working our asses off to pay for university. We left in September when all the resort towns were emptying out, and it’s not much of an exaggeration to say we pretty much had the entire country to ourselves.

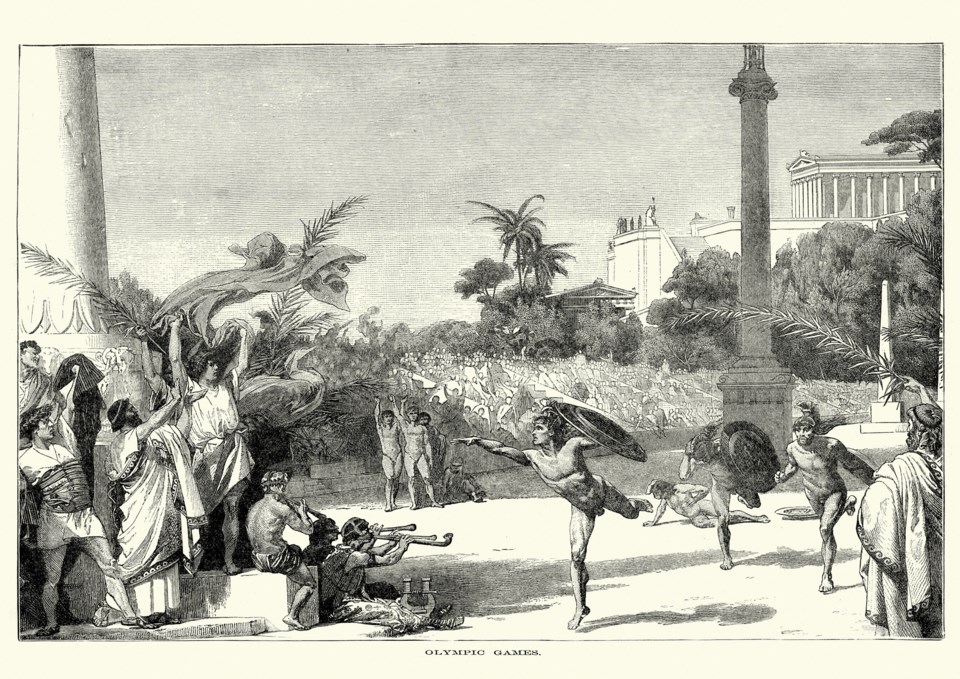

One of our mandatory first stops was Olympia, a collection of ruins that hosted the original Olympic Games for almost 1,300 years starting in 776 BC. The only tourists there, we jogged through the very same stadium arch that athletes representing the major Greek city states walked through to compete in various contests. We raced each other around the track. We wrestled. We did burpies. We tried to have a chariot race until the groundskeeper asked for his wheelbarrow back. It was great day.

After thoroughly enjoying the ruins, we moved on to the archaeological museum that housed a collection of marble sculptures of top athletes immortalized for their prowess with javelin and discus, or who could run the fastest, lift the most, or beat all comers in wrestling. In one corner of the museum sat a massive rock weighing 316 pounds, inscribed with the name of an athlete who could lift it over his head with one hand. That’s immortality.

The city states of Greece were often at war with each other in those ancient times, but contingents travelling to and from the Games were protected by a truce that is one of the Games’ oldest traditions. As a rugby player, I liked that. My sport of choice sometimes felt like 80 minutes of war followed by however many minutes I could function at the pub afterward with players from the other team.

I always enjoyed playing sports, but for me, it was more about the handshakes than the competition itself, that moment you stop trying to beat each other and all the hard feelings are replaced with respect.

The Olympics, by now heading into their second week, has done its best to bottle that feeling as well as the more noble aspects of the Games history, but there’s no question that the Olympic movement isn’t what it was. Why?

Corrupt International Olympic Committee (IOC) officials. Athletes loaded up with performance-enhancing drugs that got away with it while other athletes are banned for smoking pot. A history of awarding the Games to fascists and totalitarians. Over-the-top displays of nationalism by athletes and fans, and poor sportsmanship between competitors. Host countries taking on crippling debt, partly due to the inclusion of fringe sports that require a massive investment in infrastructure. The buying of medals by high-income nations that have the most money to throw at athletes and coaches, or lobby to protect a few sports that only they play. A ridiculous selection of random competitions that people forget exist for four years at a time. The weird fashion show at the opening ceremonies. The cliché athlete profiles. I could go on.

And talk about overkill. There are 34 gold medals available in the swimming events, 15 gold medals for shooting, 10 gold medals for track cycling—but only two gold medals for sports like sevens rugby and soccer where athletes have to play. Sometimes it feels like the Olympics is three weeks of people diving in pools and the swimmer in the middle lane finishing first.

Remember when the IOC temporarily cancelled wrestling because of poor TV ratings? Not only is it one of the first Olympic sports and the cheapest to stage, it’s also one of the few events where athletes from small and low-income countries could compete on an even footing. Meanwhile the Olympics continue to host a dressage event where people put on suits and see how stiffly they can sit on their expensive dancing horses.

The IOC is also desperate to remain relevant for the benefit of their sponsors, which is why the 2021 Games will include TV-friendly sports like surfing, skateboarding, karate and sport climbing. While I support their inclusion, I’m also afraid that these sports could be hurt by the “Olympic curse.”

The curse is real. One recent example is the winter sport of halfpipe. In the early days of snowboarding, a halfpipe was just a depression in the snow with two-metre-ish walls that you could boost out of and that anyone could ride. Then the sport became Olympic and “superpipes” had to be built with 5.5-metre walls of almost vertical ice that are incredibly daunting for recreational skiers and riders—not to mention incredibly expensive to maintain. The result was that average people stopped riding the pipe and ski hills could no longer justify the investment in their upkeep. Halfpipes started disappearing everywhere, including Whistler.

And yet, for all of its failures as an event, as a movement, as an inspiration, as a revenue generator for the hosts, as a uniting force for the world, as an avatar of the human spirit and true sportsmanship, I also know I’ll also be tuning in to the Games every single day until its over, looking for the reminders of why we play sports in the first place.