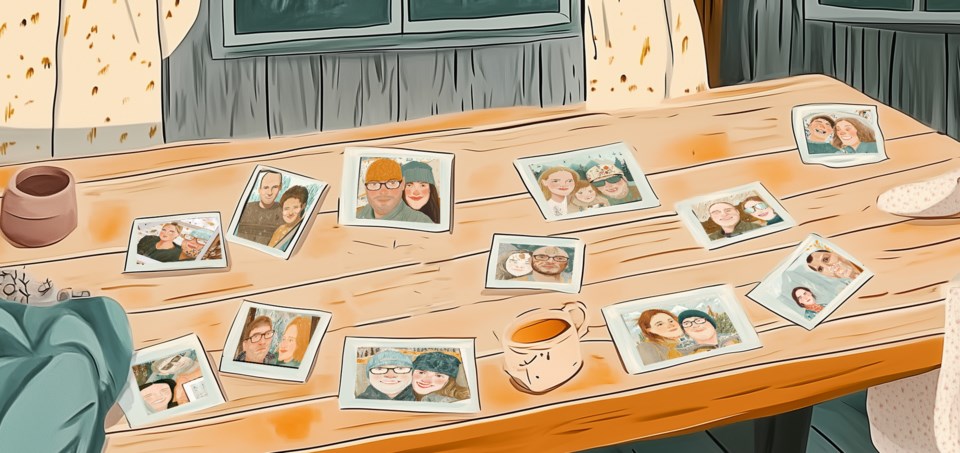

Twenty-nine years ago, in a borrowed condo in Whistler (thanks Peter and Teddi), I married a guy I’d known for about two weeks. It wasn’t for the visa, although my visa was about to run out, so I can see how it looked.

People had opinions. Some were bold enough to out-loud them: “Are you pregnant?” “I would have married you if it was for the visa.” “I thought you were smarter than that.”

We were both in casual relationships with other people. Mea culpa. It was scandalous for about five minutes until everyone moved on. (Admittedly, it might have taken those two other people a little bit longer to move on. Sorry about that.)

I remember thinking: this story will be better when we’ve been together a while. At the time, explaining that “I just knew he was the one” was an invitation for a storm of doubt to move across their faces. It was hard to fill in my permanent residency paperwork imagining how it would read to a government bureaucrat who wore cynicism like synthetic socks, as sweat-inducing as they are, because they never shrink in the wash.

It’s easier to be cynical, than hopeful, about everything. Especially about love. There’s science now that says people generally presume that cynics are smarter. It’s safer to bet against unicorns—bet on the magical and you do risk looking like a fool. Hedge, mock, poke holes from the sidelines, and you’re insulating yourself from seeming gullible, naive, wrong. Unfortunately, as researcher Jamil Zaki has found, your cynicism also perpetuates the worst outcomes. “We perceive our species to be crueller, more callous and less caring than it really is" and experience a sense of grim satisfaction when proved right, he writes in his book, Hope for Cynics. But we might have enabled it. “When we expect little of others, they notice and we get their worst.”

Tellingly for 2025, he also writes: “Autocrats love a cynical population, because a group of people that don’t trust each other are easier to control.”

I’m not writing this to crow. Relationships are mysterious continents—you can make assumptions about the terrain and weather from off-shore, but no one knows what it’s like to move one foot in front of the other within those unchartered landscapes. More than anything, I am aware of my own luck.

To be honest, I think I arrived in Whistler as someone cynical about romantic love. This place awakened in me the person who believed in audacious possibilities. I share this, because I don’t think it’s just me. I think that is a Whistler story. Even though it sometimes feels like everything has changed since my version of Peak Whistler (1996 to 2009), I hope this persists.

The ceremony was officiated by Florence Petersen, a little gnome of a woman with curly hair and wide eyes, who’d started the Whistler Museum as a promise to honour the stories her neighbour had told her about the early days of Alta Lake. Through Florence, I had a little connection to Myrtle Phillip, and Whistler’s settler lineage. I ended up volunteering for the museum, pulled into engagement by Florence’s neighbours, old family friends of my new husband. My first writing project was for the museum, a column in Whistler This Week, that was part of the Whistler Question, where I later wrote another column, until Glacier Media, the Question's parent company, acquired Pique, where I wrote another column. Thus our lives unfold, a series of unexpected pocket-shots after one ball was hit into a different direction… And a 20-year-old Australian law student became three things that were not on the Life Plan script she’d been handed: a wife, a Whistlerite*, a writer. (*Technically, I became a Pembertonian, but that doesn’t start with W, so I pulled creative licence for the trifecta.)

I just found a letter my dad wrote me one week after the shock wedding/elopement. “Didn’t think there was anything that could surprise Grandpa and I anymore, but wow you just did.”

Dad was a bit of a cynic. “It sounds negative, but I like to look at things from all angles,” he wrote, and then reamed off a list of catastrophic possibilities, wondering how we might have factored them into the plan. Which maybe all boiled down to his final question: "If you found your destiny, why didn’t I? Did I just not try hard enough?”

I still don’t know the answer to that. In hindsight, I can see how generous and gracious and genuinely curious his questions were. All I do know is that I lucked upon the right conditions.

There are some places that disrupt the trajectory of peoples’ lives—give them the space and time to think about things differently, to discover themselves outside the packaged-up life imagined and laid out for them.

Whistler was the environment in which I could slip off the straitjacket and suit I’d been expected to wear, and try on some different costumes: nanny, ski instructor, volunteer, writer, wild and spontaneous romantic, climber. I was inspired by all the different ways people were approaching aging, work, art, meaning-making. I still am.

I think that’s why I feel feisty and protective towards this place and crusty when it changes in ways I don’t recognize… because I don’t want it to lose that essential quality, of being an environment that lets people become what didn’t seem possible in the places they came from.

Does that still exist?

Do you recognize it? Are you cultivating it? Those of us who have managed to stay here, who experienced the life-changing unicorn-like magic of that, have some obligation to set the protective cloak of cynicism aside, and perpetuate possibility, or conditions conducive to it. That is how you keep a place alive and thriving and generative. Who did you wonder you might be, given the right space and circumstance and influence? What is the most audacious version of yourself? What unexpected thing might you fall in love with? Chase that. Court that. And cultivate the conditions for that, for everyone.