Some time in the early 2010s, I was working at a local backcountry gear store here in Whistler and sitting through a semi-annual product knowledge session. The store was one of the largest carriers of the Arc’teryx brand in the Sea to Sky corridor, and the rep was back to run the retail staff through the latest garment releases.

After the brand spiel and the requisite oohs and ahhs over the new product we were tasked with selling to customers, one associate asked the rep about the environmental impact of this very expensive Gore-Tex jacket.

“We do use chemicals that are harmful to the environment,” he replied. “But we build the jacket to last much longer, so the customer has to replace it much less frequently.”

Having taken a course on life-cycle analysis in university, I understood this justification. Even if every jacket sheds a small amount of harmful chemicals (that don’t degrade) over the course of its life, the overall environmental impact of making a whole new jacket is far greater.

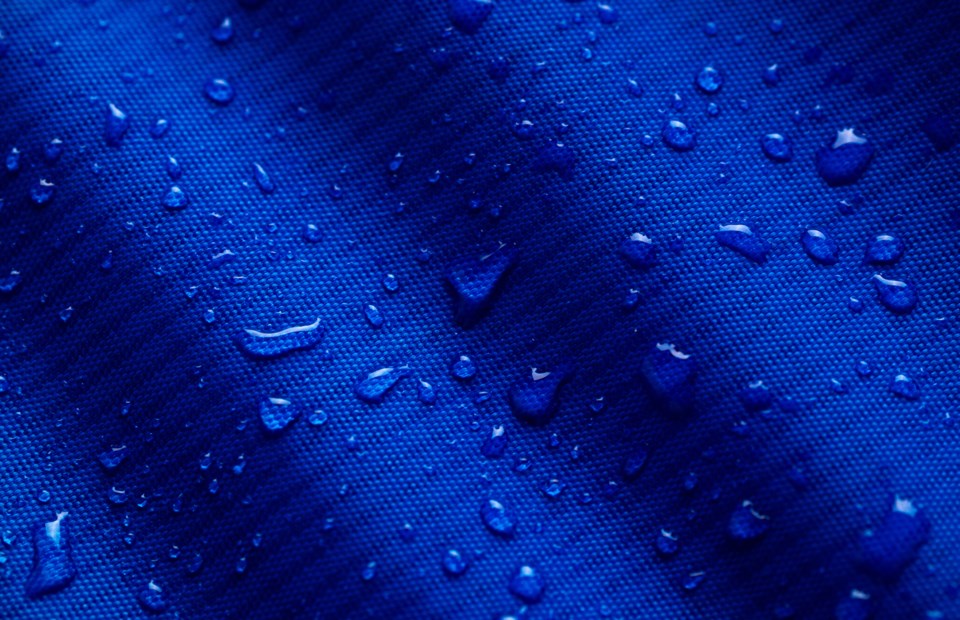

Technical outerwear has been at the whim of these harmful chemicals for decades. Let’s start with the first barrier against moisture getting through your jacket; the Durable Water Repellent (DWR) treatment to the outside fabric. The chemical name for DWR is “perfluorinated compound” (PFC). If you start looking into PFCs, you’ll quickly find a litany of articles highlighting their detrimental effects, including damage to the immune system in children (leading to an inability to respond to certain vaccines), increased incidence of cancer associated with PFC pollution, and compromised female fertility associated with PFC blood levels in women. So, not great.

Like all things chemistry, there are PFCs and then there are PFCs. The most harmful are the class of C8 PFCs, which—if you remember your high-school organic chemistry—is a molecule containing a chain of eight carbon atoms. After government interventions around the world, major players in the outdoor apparel industry like Arc’teryx and Patagonia phased out C8 PFCs in their DWR treatments more than a decade ago. A large driver of public awareness was the “Detox my Fashion” campaign, which Greenpeace launched against the use of PFCs in the greater clothing industry in 2011. In the place of C8 PFCs, outdoor apparel companies began using C6 PFCs (also called “short-chain PFCs”), which linger less in the environment and human bodies than C8, but in the grand scheme of things, still aren’t great for the planet, or its inhabitants.

The wake-up call to the outdoor apparel industry has triggered a sort of sustainable DWR arms race among manufacturers. Chemists are pursuing everything from silicones to unmodified plant wax. The issue with many of these experiments is the water repellency doesn’t hold up over time, effectively removing the “D” from DWR. But they are getting closer.

Helly Hansen claims to have achieved proper water repellency without PFCs with its new Lifa Infinity Pro fabric. It integrates the waterproofness into the fabric and yarn, eliminating the need for harmful chemical treatment to the outside of the garment. The downside is the fabric has next to no stretch, so it will have less appeal for activities like climbing.

Looking at what the other top apparel brands are doing, there seems to be a consensus that only the highest-level “pro” gear should need PFCs. This is gear high-performance athletes (like mountaineers) require for special situations, such as being exposed to rain and snow for more than 24 hours straight, where getting wet could mean the difference between making it home alive or not. Despite how extreme the regular Joe backcountry skier thinks he is, he can probably survive a day in the Duffey without PFCs in his outerwear.

As we all transition away from PFCs alongside our favourite brands, until there’s a veritable new breakthrough in DWR chemistry, we should all manage our expectations of what the garments can and can’t do. You’ll be paying the same for the new garment, but your jacket will be wetting out sooner and require more frequent washing and DWR treatment. This is a compromise we all need to get comfortable with.

Gore, which owns the intellectual property for Gore-Tex and supplies much of the industry with its fabric technology, has officially begun phasing out its PTFE (Teflon)-based membrane, which contains PFCs. This is the layer with that magical quality of keeping water out while letting vaporized sweat escape, otherwise termed “waterproof breathable.” In its place is a PFC-free version, which Gore calls ePE, another confusing acronym for “expanded polyethylene.” Since this layer is sandwiched between two layers in the jacket’s fabric, the end user shouldn’t really notice the difference of a PFC-free membrane. Short- to mid-term reviews on the ePE membrane haven’t brought up any concerns, but the long-term durability of ePE membranes will be revealed as they enter the consumer market over the next few years.

In the meantime, look after that old Gore-Tex jacket and make it last. You may never get a chance to replace it with one as good.

Vince Shuley appreciates his waterproof breathable garments and treats them with respect, as well as DWR about once or twice a season. For questions, comments or suggestions for The Outsider, email [email protected] or Instagram @whis_vince.