Well, Tom Thomson came paddling past / I’m pretty sure it was him

And he spoke so softly in accordance / to the growing of the dim

He said, “I’ll bring on a brand new renaissance / ‘cause I think I’m ready

When I was shaking all night long / but my hands were steady”

— The Tragically Hip, “Three Pistols,” Road Apples, 1991

It’s a big tell that a song written more than 70 years after its subject’s death was still instantly recognizable—no questions asked, no explanation necessary—by the generation it was birthed into. Such is our national fascination—nay, obsession—with painter Tom Thomson.

“If you ask someone who their favourite Canadian artist is, a high percentage will say Tom Thomson,” notes Audain Art Museum director Curtis Collins. “But if you ask them what their favourite movie is, they don’t go back to silent films as their point of reference.”

And yet, though Thomson’s name and century-old works still resonate with oddly urgent pop-cultural cachet, there are even deeper, uncelebrated reasons for his contemporary relevance. “You can view any art exhibition through multiple lenses,” adds Collins, “and the greater latitude you have with the experience, the more you’ll take away.”

Suggesting that no matter what visitors glean from a spin through the Audain’s current show, “Tom Thomson: North Star,” more subtle juxtapositions are to be extracted when the work is viewed beyond typical art-appreciation parameters like embodiment or rendering.

There is, naturally, an art-history perspective, the risks Thomson took with colour and technique that shine in the small sketches gathered by the Audain—painterly Polaroids of what he really experienced before transforming some into more-staid studio works. But there’s also an environmental perspective, covering not just the legerdemain of access to “iconic” scenery, but the style that gives cover to what the artist really exposes. Finally, there exists a socio-cultural-political perspective in which the circumstances of the times shed less-flattering light on what we see.

To begin, some perspective on the development of art in Canada, which, like most advancements in the early colonial dominion represents an import—or at least logical derivation. “Essentially, what we see at the time are Thomson and others grafting the techniques and concerns of European post-impressionists onto the Canadian landscape,” says Collins.

But the Canadian landscape reflected back more than the bucolic scenes of cultivated fields and hay bales spotting rolling countrysides, city parks, or emerging technology captured by post-impressionist French painters. It was alive in a way that commanded attention, seen in the verve of Thomson’s more innovative moves as a painter.

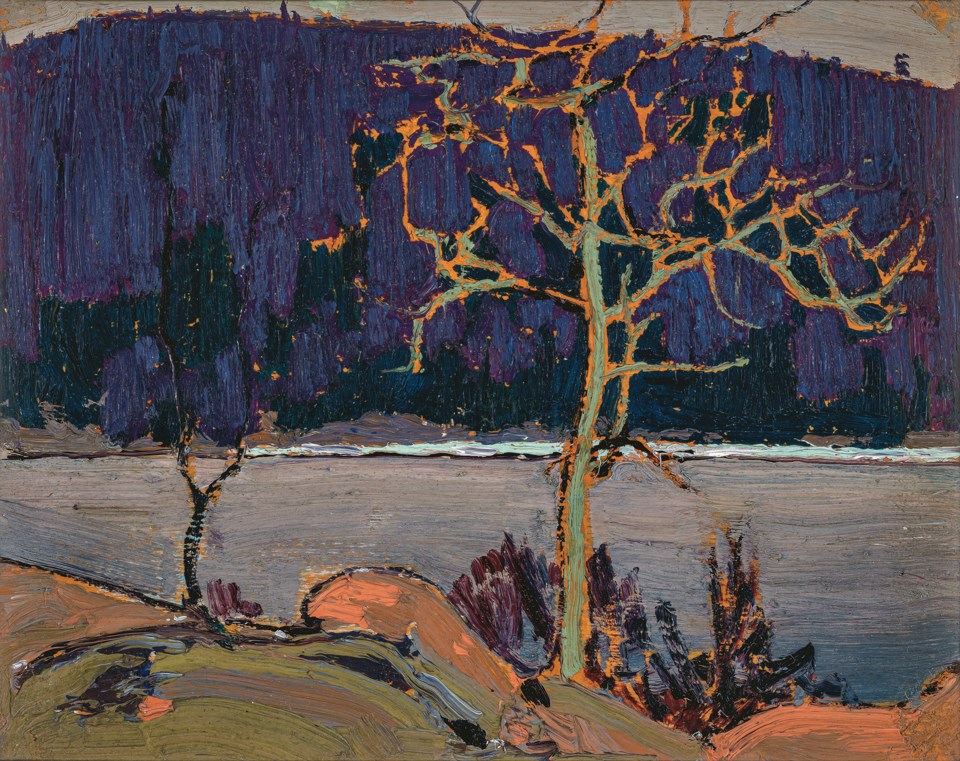

Complex colour schemes and bold brush work rejected the received pastoralism of the time—a generational shift that reverberates into the present. “He was a very intuitive painter, responding to the landscape with an unparalleled immediacy in palette and brushstroke,” notes Collins of a characteristic not quite as evident even among Thomson’s Group of Seven buddies (despite the frequent assumption he belonged to the venerable cabal, Thomson was only Group-of-Seven adjacent—like B.C.’s Emily Carr). “You can see this by comparing his sketches and studies—which literally crackle with the moment they were made—to larger studio pieces that feel more constructed and stilted.”

Regardless of provenance, all Thomson’s imagery promotes a raw, terra nullius vision of the country, as celebrated in his quintessential final painting, The West Wind, completed just months before his tragic 1917 accidental drowning (or was it?) in Algonquin Park’s Canoe Lake and immortalized as “the spirit of Canada made manifest in a picture,” by the Group of Seven’s Arthur Lismer.

Though a main connection point with Thomson’s work, there’s a problem with this view: if it existed at all 300 years into a fur and timber trade that laid waste to Canada’s forests and wildlife, terra nullius wasn’t to be found in the compromised environs where Thomson laboured over canvases.

The early 20th century represented first-generation tourism in Canada, which followed the route of the transcontinental railroad in the western mountain parks, but in Ontario comprised the near-north “wilderness” of Algonquin Park. Established in 1893—not to stop the logging levelling it but to create a wildlife sanctuary and protect headwaters of the major rivers flowing from it—Algonquin became a destination for sightseers and fishermen like Thomson, who came by train and generally stayed at one of its several lakeside hotels. Thus, while Thomson carries much of the water for Canadian self-identity as a relationship to wilderness—reflected in photos of his time in Algonquin as an adventurer clad in woolly socks and breaches sleeping in a damp, buggy, canvas tent—he gained access only because of the unsustainable, rapaciously wasteful logging and other extraction enterprises of the era that, in the way of all monopoly capitalism, built private railroads to exploit resources and bring in settlers.

This isn’t an indictment but a simple reality—one seldom reflected in the received view of Thomson’s art. In Tea Lake Dam, however, what’s missing says it all: the forested area viewed today at this picnic site is treeless in the painting. Still, Thomson did occasionally depict abandoned logging machinery and, in one instance, longboats full of loggers paddling a lake—often mistaken for First Nations canoes. Which brings us to the socio-cultural-political front.

Moving into its own as a nation state, Canada was in need of identity that Thomson and the Group of Seven helped deliver. In the process, however, Indigenous peoples were excluded. Having been moved out of their traditional lands and onto reserves after the 1850s, by 1900ish First Nations had been erased socio-culturally and politically (as non-voting wards of the state). And so we see empty, unoccupied Algonquin landscapes that reverberate with the height of oppression of First Nations in central Canada.

Unsettling as it is to go beyond cherished ideals, there’s also the complex problem of Thomson himself. His description as a loner has led to all sorts of speculation, including that his frequently employed lone-tree trope (like Purple Hill, pictured here) was self-referential, such that the single, wind-lashed, misshapen pine depicted in The West Wind is no portal to the beauty of a landscape beyond—a landscape that may or may not, along with its occupants, have been erased—but an anchor for the one image that seems rooted in our collective psyches: a man alone against the north.

“Tom Thomson: North Star” ends Oct. 14. Be sure to check out the Audain’s next large show, “Curve! Women Carvers on the West Coast,” which covers 14 female artists from the 1960s to the present with.

Leslie Anthony is a Whistler-based author, editor, biologist and bon vivant who has never met a mountain he didn’t like.