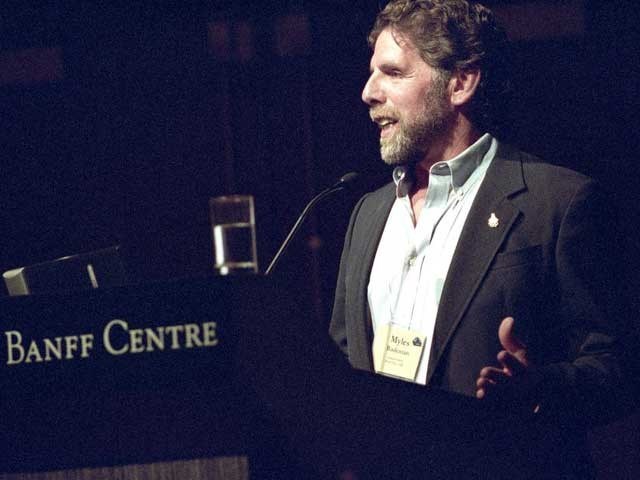

“The landscapes that we see are the

landscapes we believe in…”

– Myles Rademan

By Michel Beaudry

He bills himself as a reality therapist. No, I’m not joking. Part teacher, part scientist, part entertainer — and full-time social agitator — Myles Rademan’s approach to mountain town management is a little bit akin to Freud’s approach to human psychology.

Ask a lot of questions. Probe behind the mask of convention. And don’t be afraid to say unpopular things.

OK. So I’m exaggerating a little. So psychology is a bigger subject than mountain town life. So sue me. What I’m trying to say is that this Rademan guy has been probing the psychic closet of mountain communities for a long time now. And we should all be listening a little closer to what he has to say.

Consider the recent Travel Symposium in Vail where the much-hyped keynote speaker exhorted the resort-business crowd to “over-promise and over-deliver” (once again). Rademan, who was participating in an experts’ panel following the speech, raised the one question on everybody’s mind: “So who is going to do all this over-delivering for you?” They say he got the biggest applause of the week…

“To me, it’s straightforward,” says the veteran planner. “The social contract that once defined life in mountain towns doesn’t exist anymore. And everybody knows it. In fact, what was once a pretty egalitarian lifestyle has all but disappeared today. The workers have been disenfranchised and the gulf between rich and poor is getting bigger. We still have great towns. And we still get scenery dividends for living there. But much of the work today is being done by migrant workers. So what does that mean for the future?”

Turns out that was a rhetorical question “Reality sucks,” he says. “But it’s the only thing we have to work with. Anytime there is life, there will be winners and losers. Life isn’t fair — get used to it.” He stops speaking. Picks his next words carefully. “As a community grows and changes, some people adapt and thrive and some miss their turn — and become bitter. It’s a very common occurrence in resort towns. Particularly now, when bigger and better players are attracted to the game. But that doesn’t mean we just throw up our arms and give up on the issue.”

He smiles — if just a bit sadly. “I’m a social observer. And yes, I see trends out there that worry me. But I also understand that we have to establish functional economies in these towns. My gift is that I can speak. I’ve woven my observations into stories where I can talk about some of these trends and issues.” He laughs. “But I certainly don’t advocate for a return to a past that may or may not have happened…”

Rademan is one of those eccentric people who still believe in small-d democracy. “I just look at the root of the word ‘community’. Common + Unity. I believe that local self-determination has a really big role to play in this. But that means actively embracing everybody in the community — not just the rich or the powerful or the old-timers or the great skiers or the whatevers. It means everyone. That’s where the real story lies.”

And so the reality therapy continues…

A frequent speaker at resort conventions and town-planning seminars across North America — as well as a Fulbright scholar and a Kellogg National Leadership Fellow — Rademan brings a unique tough-love-meets-cheerleader spiciness to his presentations. “A lot of the towns I consult for are like outpatients,” admits Rademan, with only a hint of a smile. “Seriously — as an outsider, I can hold up a mirror to them and say: ‘This is what your problems look like.’ And when I get their attention with a little humour, I can then say: ‘Here are a few examples of what other towns are doing about it…’”

Then comes a long moment of silence. “Unfortunately, there aren’t a lot of examples of mountain towns that are managing change all that well right now,” he eventually says. And shrugs. “But at least, some of them are getting some of the things right...”

Rademan gets it. Or at least, it sounds to me like he gets it. With over 35 years of experience in mountain-town planning — first in Crested Butte, Colorado and then in Park City, Utah — Rademan represents a perspective that values, as he puts it, “working more on the human side of things than on the bricks-and mortar thing.

“One of my biggest roles has been to nurture the web of personal relationships that make up mountain communities,” he says. “I’m constantly railing against the urge to build more ‘stuff’ in resort towns.” He sighs. “At some point, we all have to realize it’s the people that count… not the stuff.”

He continues: “I was lucky to be part of a group of long-haired kids who ‘took over’ the town of Crested Butte in the early 1970s. It was a fabulous experience. People forget just how depressed that place was before the hippies arrived. We organized the town again. We put Crested Butte on its modern footing.”

It’s clear that his years in southwestern Colorado mean a lot to Rademan. “I was never a skier before that,” he tells me. “Wasn’t part of my life. Zero. I grew up in Philadelphia. I didn’t even have friends who were skiers.” And then he laughs. “I remember the only ski trip I did when I was a kid was to the Catskill Mountains. I hated it. It was so cold…”

Life certainly moves in wild and wonderful ways. Shortly after graduating from New York University in 1970 (with both a law degree and a masters in urban planning), Rademan was recruited to work on former President Johnson’s ‘war on poverty’— “we’re always fighting something in America,” he says only half-sardonically — and joined the Colorado Rural Legal Services. “But I never ended up working there,” he says. “Instead, the city of Denver decided I should become a planner in a predominantly Chicano neighbourhood.” He pauses for just a beat. “I didn’t even know what a Chicano was back then…”

But that didn’t stop Rademan. In time he became a fierce advocate for his new neighbourhood — so much so that the city of Denver couldn’t wait for his grant to expire so they could get rid of the guy. Meanwhile he was hanging out with a gang of young Colorado lawyers who were living the Rocky Mountain lifestyle. “A friend of ours had ‘discovered’ Crested Butte a few years back and bought a big ranch up there,” he explains. “So that’s where we’d go skiing…”

A former coal-mining town, Crested Butte was little more than a huddle of dilapidated high-mountain shacks when the first wave of skiers arrived there in 1969. But the powder was light and the local scenery was gorgeous. Soon, CB was being settled by a new tribe of long-haired skier types; by 1972, they’d voted themselves into municipal office. Then they realized they didn’t know the first thing about governing…

“I remember meeting the town mayor, Bill Crank, on one of our first trips,” says Rademan. And laughs. “We were both young, both of us had long hair and beards. And he said to me: ‘I don’t know the first thing about running a town. And I hear you do. If you can figure out a way to write yourself a grant, then you can move here and become our town planner.’ So that’s what I did. I got a $6,000 grant — split it three ways — and we ended up staying there for 15 years.”

That’s also where Rademan got his crash course in skiing (no pun intended). “I had friends on the ski patrol,” he remembers. “And they told me: ‘the only way to properly learn to ski is to follow us.’ What did I know? I was just this urban kid from Phillie. So I did.” He stops for a moment. Shakes his head in mock despair. “They all had nicknames for each other. One was Sergeant Swift. Another was Captain Courageous.” A long pause. “I became known as Corporal Punishment.” Ta-dum-pump.

Though he loved the activity-filled lifestyle of Crested Butte, Rademan was known first and foremost as an office guy. “I was the grant writer,” he says. “I ‘did’ planning. I was the paper pusher.” Another big smile. “Even my clunker was dubbed ‘the bureaucrat’ …”

Still, when the time came to leave his idyllic valley behind and move on to bigger projects in 1986, Myles knew he’d be leaving part of his heart behind. “Being offered the job of planning director for Park City was a big step for me,” he explains. “And the timing was right for our family. But it was a tough leave-taking nonetheless.”

Was it the right move? No question, says Rademan. “I’ve had the opportunity to help grow this place for 20 years. I was part of an Olympic prep-and-Games cycle. And you know what? I like the community that Park City is becoming now.”

And his skiing? “I’m no more hardcore than I’ve ever been,” he says. And laughs. “A big outing for me is making it up to Deer Valley around 11, getting a couple of runs in, then having a nice lunch and lounging in the sun a while. To me, that’s a great ski day…”

Next week: Myles Rademan’s Ten Olympic Lessons