Just how many communities can boast that their first news reporters were a group of schoolchildren? Like most of Whistler’s history, the history of print news in Whistler is far from conventional, and relied heavily on community input, support, and organization.

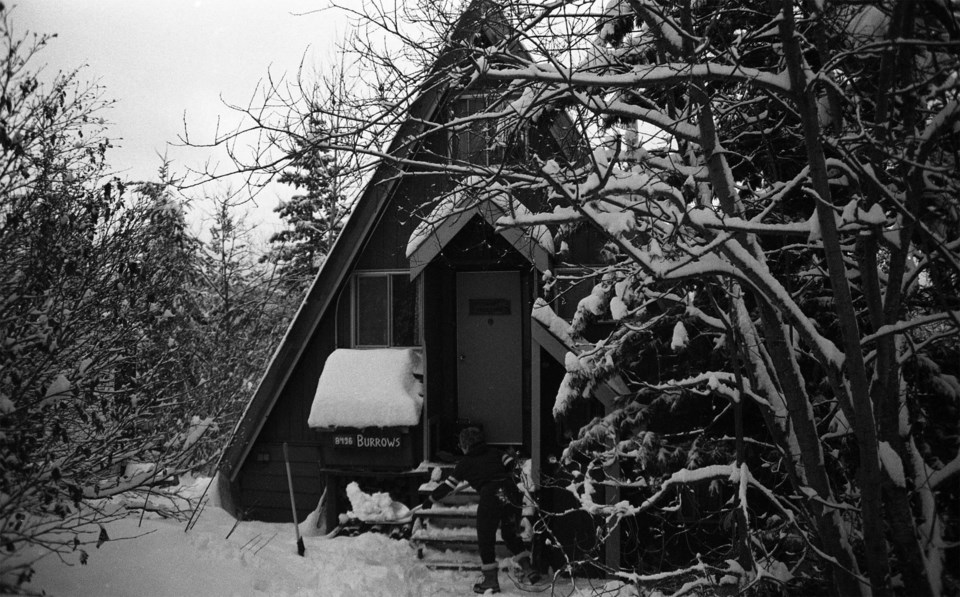

The Whistler Question was published for the first time in 1976 from the basement of the Burrows’ home in Alpine Meadows, and, although it was the first newspaper about the valley, it was not the first source of community news.

Early reporting in Whistler (circa 1930 to 1960) often centred around events that many would no longer consider newsworthy. Reports of gatherings for tea and details of newcomers in the valley featured prominently in Whistler’s (then Alta Lake) early newsheets. Whistler is by no means a roaring metropolis now, but the small community of Alta Lake was a fraction of the size, and the reports showcase the quiet life many residents led.

The first newsheet in the valley was the Alta Lake School Gazette, a single-page publication put together by a group of students at the Alta Lake School. It had a total of six issues, and ran from February to June, 1939.

The second newsheet was published by the Alta Lake Community Club from 1958 until 1961. The single-page publication changed names a few times before the Club settled on the Alta Lake Echo. As of its second issue, it featured a subtitle that read “published for fun,” which highlights the nature of the sheet. It was never intended to be a serious newspaper, and it never became one. Rather, it was a way for residents to be kept up to date with the goings-on of the past week, and informed of upcoming events.

By the time the Question was introduced, the community had changed significantly. Its first edition was published mere months after the Alta Lake community had been incorporated as the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW). Despite the significantly larger readership warranting a different approach than earlier publications in Whistler (just imagine if an article was written for every new arrival or departure from the valley), the Question nevertheless still encouraged, and relied on, community involvement.

The Question featured many different columns, some more conventional than others. A perennial favourite, called “Bricks and Roses,” was published for much of its existence, and was in some ways reminiscent of a quieter time in Whistler when community happenings made up all of the news.

The idea for the article was suggested to current Pique columnist Glenda Bartosh (then editor of the Question) by Gary Raymond, who at the time was treasurer at the RMOW and had seen a similar column in a Quebec newspaper. A few months before it was introduced, the editor’s column had encouraged readers to send in their input in order to “make this community paper a dialogue—rather than a monologue.” The Bricks and Roses column set out to do just that. It created a forum for readers to express their gratitude for the good deeds of individuals and organizations by bestowing roses, or to call out and (rather publicly) condemn what they considered bad behaviour. More importantly, it gave people a direct path to the publication that did not require a comprehensive letter to the editor.

As you can imagine, people seized the opportunity to submit either a Brick or a Rose, and a wide variety of colourful submissions began to pour in. Some submissions were phoned in, while others were given verbally to one of the Questionables (name given to the staff at the Question) while they were out and about.

Keely Collins is one of two summer students working at the Whistler Museum this year through the Young Canada Works Program. She will be returning to the University of Victoria in the fall.