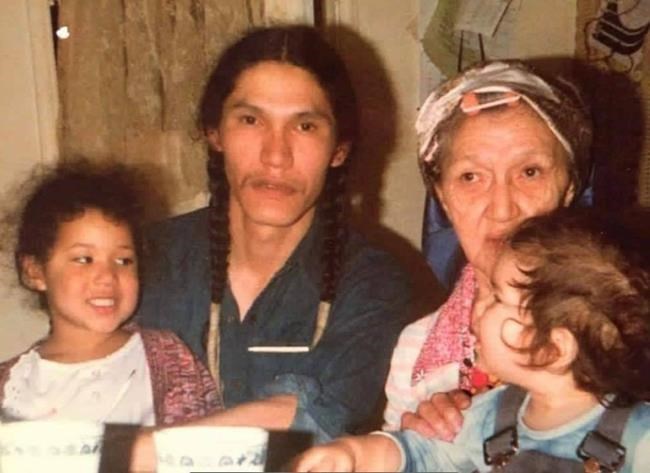

The weeds of residential schools are tangled throughout the family tree of Clayton Episkenew and many other Indigenous people in Canada.

“I have come a long way but at times feel guilty that I am here and others did not make it,” Episkenew said in a written statement to The Canadian Press.

The Regina man struggled this week with news that a search had found what are believed to be 751 unmarked graves at the site of the former Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan.

Episkenew, 42, who goes by the name Bolo, attended a different residential school at Lebret, Sask., from 1991 to 1993.

In order to start moving toward reconciliation, he said people need to understand how there is still significant fallout from what happened within the walls of these schools.

An estimated 150,000 Indigenous children were forced to attend residential schools over a century. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has detailed mistreatment at the schools, including emotional, physical and sexual abuse of children.

“Against the odds of being a third-generation residential school survivor, I am happy to be here. Glad to be alive,” Episkenew said.

His father also went to the Lebret school and told family it took 30 years to learn to love himself again.

His family said he would practice looking into the mirror and saying, “I love you."

Episkenew said he understands it was a system that forced generations of his family to go to residential schools. But, he said, it’s difficult knowing he was not spared.

“It makes me understand and at the same time resent my dad because of it,” he said. “Because he knew about it but still sent me there. He went through it and still left me there.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report in 2015 said the closing of residential schools did not bring their story to an end. Their legacy is reflected in significant educational, income and health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada.

“The disproportionate apprehension of Aboriginal children by child welfare agencies and the disproportionate imprisonment and victimization of Aboriginal people are all part of the legacy of the way that Aboriginal children were treated in residential schools,” the report said.

It detailed how some schools were more like jails. There were punishment rooms and numbers for students instead of names. Children were sometimes chained together or shackled to their beds.

“They treated us like criminals,” Joseph Martin Larocque, a former student at the Beauval residential school in Saskatchewan, told the commission.

Episkenew said the school he attended removed his connections to cultural traditions. By stripping his identity, the school created a perfect storm that put him onto a path of alcohol, drugs and encounters with the justice system.

The proportion of Indigenous people in federal custody hit a record high last year. More than 30 per cent of men incarcerated were Indigenous, and 42 per cent of women were Indigenous.

Statistics Canada said Indigenous youth, while making up eight per cent of the total youth population in 2016-17, were 46 per cent of admissions to correctional services.

In the provinces, the numbers of Indigenous youth in custody were highest in Saskatchewan during that time (92 per cent for boys; 98 per cent for girls) and Manitoba (81 per cent for boys; 82 per cent for girls).

There were also more than 3,400 children in care in Saskatchewan in 2019 -- 86 per cent were Indigenous. There were nearly 10,000 kids in care in Manitoba, and 90 per cent were Indigenous.

Episkenew said he eventually left his troubled life behind.

Now, he said, "staying alive is an obsession.”

His brother, Eagleclaw Bunnie Thom, did not go to residential school. But Thom's father, Bernard Bunnie, attended Marieval.

Thom said Bunnie ran away from the school when he was 16. He ended up in Calgary, where he was killed by a man in 1985.

Thom, who now lives in Ottawa, said one of his first memories was when he was four and at his father’s funeral. He said he went to more family funerals before he was ten than most people see in a lifetime.

Thom said he stopped crying when he was a child as a way to cope. But now he’s letting himself shed tears again.

The displacement of Indigenous children in Canada is still ongoing, he added.

Identifying graves is only one step in stopping harm caused by residential schools, he said. More needs to be done to help Indigenous children.

"It only feels like people pay attention when there's dying Indians or dead Indians."

The Indian Residential Schools Resolution Health Support Program has a hotline to help residential school survivors and their relatives suffering trauma invoked by the recall of past abuse. The number is 1-866-925-4419.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published June 25, 2021.

Kelly Geraldine Malone, The Canadian Press