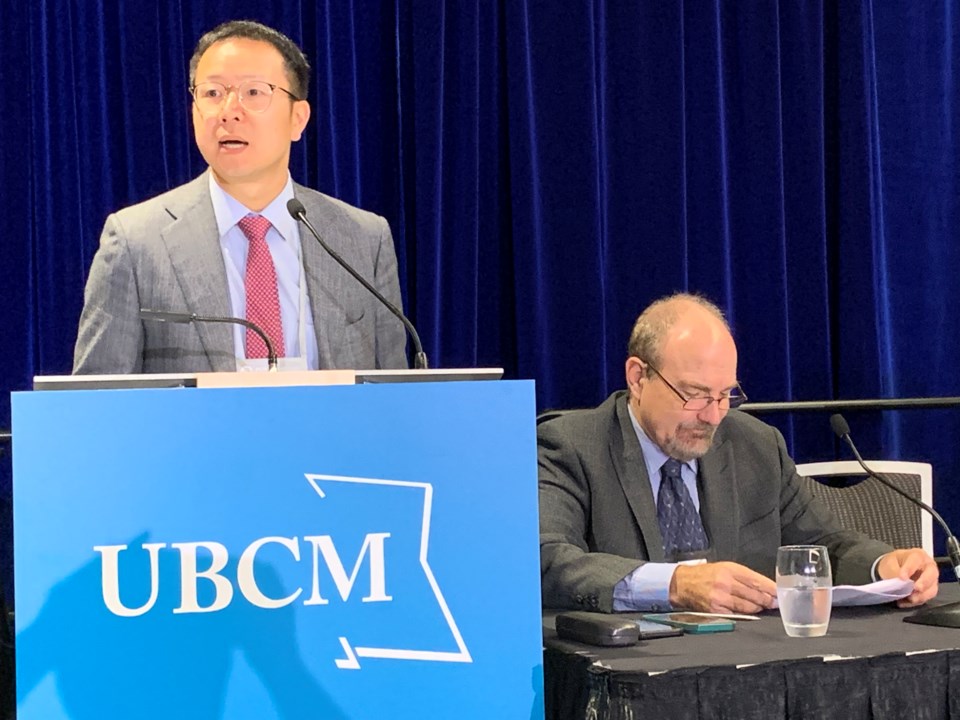

B.C.’s ongoing housing crisis requires a crisis response with a coordinated effort from all players, delegates to the Union of BC Municipalities (UBCM) heard Sept. 16.

“The housing crisis has been years in the making and it’s going to years of effort to tackle it,” said moderator Craig Hodge, a Coquitlam city councillor.

The annual UBCM convention sees local politicians gather to discuss a variety of topics: from the toxic overdose crisis and climate change to housing and homelessness. This year's conference is in Vancouver from Sept. 16-20.

Speakers told delegates that the implementation of ambitious federal and provincial housing agendas over the past year has seen far-reaching consequences for local planning and development. Further, even as local governments respond to legislative changes, more changes are on the horizon as policy development in government and across multiple industry sectors continues to evolve in response to the affordability crisis.

Bryan Yu, Central 1 Credit Union chief economist, said Canada’s market has seen turbulent times but the market is now slowing.

“We are now in recessionary conditions in terms of the sales market,” he said.

He noted homebuyers may expect to see interest rates drop sharply as both the Bank of Canada and the U.S. Federal Reserve revise rates.

Still, he said, B.C. and Ontario continue to be very expensive compared to the rest of Canada.

He said the median price for a two-bedroom condo in Vancouver is $1.3 million and $1.2 million in Toronto. In Calgary and Edmonton, however, those prices are $550,000 and $385,000, respectively.

“Kamloops and Nanaimo are more expensive, on average, than Calgary,” Yu said.

Moreover, he said, “Sellers aren’t selling. Buyers can’t get into the market.”

“Prices are going to go higher. There’s pent-up demand in the market.”

Yu said the housing supply deficit will persist.

“It’s likely not going to be fixed,” he said. “We’re building a lot but we’re not building enough.”

Generational fairness

Professor Paul Kershaw of UBC’s School of Population and Public Health said B.C. is at the centre of the country’s generational fairness issue as older people remain in their pricey homes and young people don’t earn enough to get into the market.

The founder of Generation Squeeze, a think tank aimed at preserving the ability to have a home and protecting the environment, said wages need to catch up to housing costs.

With the upcoming Oct. 19 provincial election, he said political parties don’t have clear policies on the issue.

Kershaw also took aim at taxation, noting people have wealth in their homes, oftentimes factored into retirement plans. He suggested municipalities need to assess what is rationally needed for their taxation purposes while leaving money for the landowners.

That brought Kershaw to government budgets. He said parties wanting to eliminate or cut deficit spending risk slashing old age pensions and health care and taking money out of people’s pockets. That, he said, risks removing investments seniors make in their children and grandchildren.

“An aging population dampens growth,” he said.

Terri McConnachie, executive officer at Canadian Home Builders' Association of Northern BC, also stressed the need for the government to take responsibility for its role in housing prices. She said up to 30 per cent of the cost of a residence can come from costs and fees before it even hits the market.

Market and non-market housing

The issue of market versus non-market housing was a key concept for panel members.

“We all need more housing,” McConnachie said. “We all want affordable housing.”

However, she said, the issue of creating a home involves many moving parts such developers, contractors, licensing, permitting and skilled trades, all of which can increase costs.

“One of the ways to tackle this is to slow down,” she said, noting rules and regulations keep changing.

“Speed up [building] as fast as you can,” countered Thom Armstrong, CEO of the Co-operative Housing Federation of BC, saying there has been a collision of supply and affordability.

He said there is a growing gap between what the private sector can afford to build and what renters can afford.

And, that he said, demands intervention.

The problem is made worse by the fact B.C. leads the country in evictions and no-fault evictions, leading in some cases to homelessness, delegates heard.

Armstrong stressed the need for non-market housing.

“Rents for households earning less than $50,000 a year are unaffordable in a private housing market scenario,” he said. “The more you erode affordability in the market sector, you erode affordability in the rental sector.”

He said a recent poll found 90 per cent of respondents identified housing as a key provincial election issue.

McConnachie, a former Prince George city councillor, told delegates they need to be educated as elected officials, to reach out to all parties to the housing sector to have a full grasp of the situation. Reach out to developers, permitting officials, experts and colleges training skilled workers, she suggested.

She urged them to be patient.

“You did not get elected and then the next day know everything,” she said.

Still, she added, industry wants “less government interference with great ideas.”