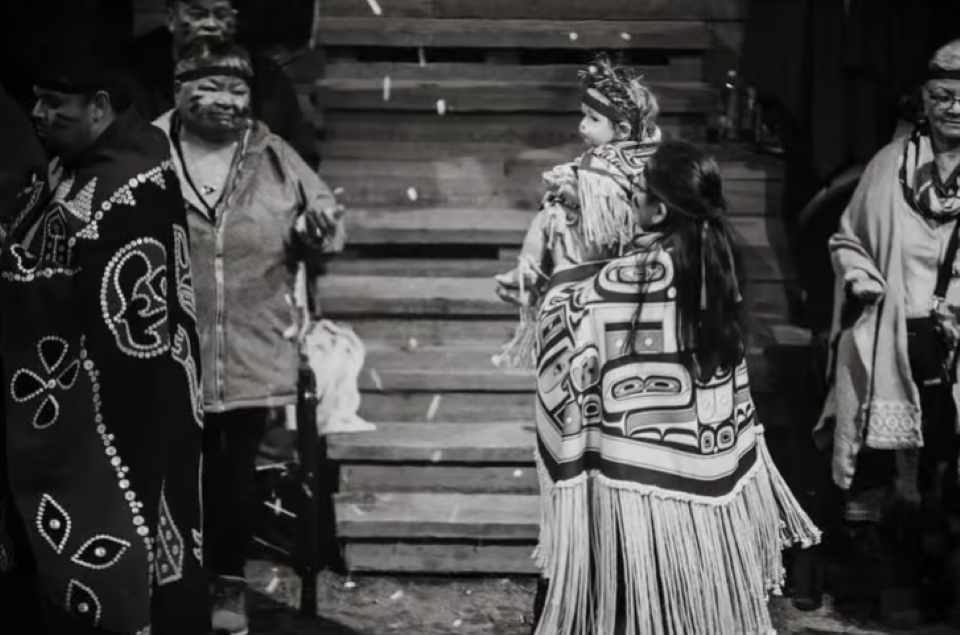

After 13 months of fighting, the parents of λugʷaləs K’ala’ask Shaw have received a birth certificate that accurately represents the spelling of his name.

It’s a victory for Crystal Smith and her partner Raymond Shaw, who have been challenging the province’s Vital Statistics branch to honour the Kwak̓wala characters in their son’s name.

According to the provincial Ministry of Health, “going forward the ability to claim names will be open to all Indigenous peoples” on birth certificates regardless of age.

Smith says it’s the start of what she hopes will become a wider movement of recognition. “B.C.” has the highest diversity of Indigenous languages in the country with more than 34 languages and 90 dialects.

According to Smith, who is Ts’ymsen and Haisla, λugʷaləs K’ala’ask Shaw’s name comes from an origin story of Shaw’s people, the Wei Wai Kum First Nation.

“There were four brothers that were hunters, and they went to Loughborough Inlet,” Smith explains.

“The older brother saw a one-horn mountain goat. He shot the mountain goat, but it didn’t fall. He followed it to the cave, and when he went into the cave, he found a man. He was a spiritual being. The older brother ended up staying there for four days, and on the fourth day, the mountain goat said that he was going to give him gifts.”

Smith says that the name λugʷaləs is the place name for that mountain from the story, and the name given to the older brother for bringing gifts down from the mountain. The name is Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, and uses phonetic symbols created by Kwak̓wala language keepers.

However, when Smith and Shaw registered their son’s birth, the Vital Statistics agency refused to accept the name. The agency would only accept names composed of Latin alphabetic letters, apostrophes, hyphens, periods and French accents. The parents filed a challenge with the B.C. Supreme Court in 2022, arguing that the agency’s naming standards violate their constitutional rights.

“The Kwak̓wala speakers worked really hard to create this written language and to change it because Vital Stats didn’t agree or recognize it just felt disrespectful,” Smith says.

Now that the 14-month-old λugʷaləs K’ala’ask Shaw has a birth certificate, Smith can stop worrying about accessing healthcare for her son.

At every medical appointment following his birth, her son was recognized only as “Baby Boy Shaw.” Smith had to explain the situation to healthcare providers during every postpartum visit, and when he had to go to the emergency room when he had COVID-19. Because her son didn’t have a birth certificate, she was billed by the hospital for his birth.

“With all the harm that Canada has caused Indigenous people, and through that harm we were able to come up with a written language, they [Vital Statistics] should be upholding that,” says Smith.

The case remains before the “B.C.” courts. According to Smith, Vital Statistics has six months to change their policies in exchange for an adjournment to scheduled hearings.

A statement from the provincial Ministry of Health says that every Indigenous person in the province should be able to have their name accurately reflected on their documents, such as an ID or birth certificate.

“Parents are able to register Indigenous names with a diacritical marker on a birth certificate with Vital Statistics. However, they must sign a waiver to understand the challenges that this may play for registering for government services,” the statement says.

“The waiver was made available to this family and going forward the ability to claim names will be open to all Indigenous peoples, not only new parents, older individuals as well.”

Vital Statistics says that they are committed to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People and the revitalization of Indigenous languages in “B.C.”

One of those actions is adopting an inclusive digital font that will allow for Indigenous languages to be included in official records, the agency’s statement says, though it did not clarify a timeline or which symbols will be recognized.

For Smith, she says having her son’s birth certificate is something to be celebrated, but she won’t be fulfilled until every Indigenous lifegiver has their chance to have their child’s name accurately represented.

“This was for all Indigenous mothers who want to name their children in their language, and to have their language respected,” she says. She hopes that their story will spark a blazing fire that leads to transformative change that honours Indigenous languages.

“My son’s name was the ember.”

The next step for Smith and her family is to apply for her son’s passport.

Smith is looking forward to taking her son on cross-border canoe journeys, something she has been worried about due to the inability to apply for a passport without a birth certificate. "It's all been nerve-wracking and frustrating," says Smith.

This is not Crystal's first time pushing back on policies that limit her ability to access her respective culture. In 2020, the B.C Human Rights Tribunal ruled in her favour for her previous landlord to pay damages for evicting her for smudging.

Crystal says that, when it comes to her son’s name being validated, she doesn’t even consider it a step in the right direction, as it’s something that should have been done long ago.

“I don’t want [Vital Statistics] to use this as a pat on the back for reconciliation,” she says.

“When mothers don’t have to endure birth alerts, when they are able to name their children, that's when they are stepping in the right direction. Right now, it’s just a turn. For me, that’s not something to be proud of.”