It could have been an infected cougar or maybe a handful of house cats. What's certain: in the spring of 1995, heavy rain washed feline feces laced with millions of parasitic eggs into Humpback Reservoir. Within weeks, over 100 residents of Victoria, B.C., fell ill with toxoplasmosis in the largest outbreak of its kind ever recorded.

On the lookout for fever, eye problems and brain swelling, health officials tested at least 5,000 pregnant women for the parasitic infection.

"Babies at risk? Testing will tell," read one Times Colonist headline as health officials scrambled for answers.

"Health scare turns cats into pariahs," read another.

A protozoac parasite smaller than the width of a human hair, you'll find toxoplasma gondii virtually everywhere you look.

"It is so pervasive. It is the most successful life form on the planet," said Kevin Lafferty, a senior ecologist studying parasites with the US Geological Survey. "It's 8,000 feet up in the air in geese; it's 8,000 feet below the surface of the ocean in sperm whales. It's on every continent, including Antarctica."

At once neglected and endemic, researchers suspect the parasite could have already infected up to half of humanity.

Yet without cats, toxoplasma (or T. gondii) would face an evolutionary dead-end. That's because its life cycle depends on making it back to the cells that line a feline's intestine.

The oocysts, or eggs, are shed into the soil with cat feces. From there, it passes through water or onto plants where any warm-blooded animal, including humans, ingests it. That could put some gardeners at risk. But infection can also spread through what you eat, and a slice of medium-rare pork or undercooked chicken could end up transmitting the parasite across your dinner plate.

In the U.S., toxoplasma is estimated to lead to eight per cent of all hospitalizations due to food illness, costing the country an estimated $3 billion every year. In Canada, its prevalence is not as apparent, though some estimates in Indigenous communities suggest up to a 65 per cent infection rate. And in one 2018 Health Canada study, the parasite was found in 4.3 per cent of fresh ground beef, chicken breast and ground pork bought across supermarkets in British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario.

Once infected, the parasite can lead to flu-like symptoms, cause damage to eyes and internal organs and lead to encephalitis. People with compromised immune systems and pregnant women and their fetuses are especially at risk of severe illness and even death.

Those clinical symptoms alone are enough for doctors to recommend pregnant women stay away from a domestic cat's litter box. But like the thousands of Victoria residents thought to have become infected in the 1995 outbreak, many will never notice they have caught the bug.

That's where things get weird.

A SCI-FI VILLAIN?

In the early 1990s, scientists in the Czech Republic started testing how the parasite might be affecting human personality through a form of gene manipulation in the amygdala, which among other things, regulates emotion, memory and the fight-or-flight response.

A decade after the outbreak in Victoria, Lafferty joined a growing number of parasitologists obsessed with toxoplasma, leading him to question, could it be influencing entire cultures?

In 2006, Lafferty published a study examining infection data on the parasite in dozens of countries. He found some striking correlations between infected people and their behaviour: infected women showed increased levels of intelligence, were more likely to follow rules and were more compassionate; infected men, on the other hand, showed lower levels of intelligence, were more frugal and mild-tempered. Infected people of both genders appeared to be more prone to feelings of anxiety, guilt and self-doubt.

Since then, Lafferty says other research has suggested a person's blood type (particularly, those who are Rh+) could offer protection from the parasite's worst effects.

A wave of research followed. In 2018, a study found entrepreneurs who tested positive for the parasite were 1.8 times more likely to have started their own business. At a global level, nations with higher rates of parasitic infection had higher rates of entrepreneurial activity and were less likely to cite "fear of failure" when starting a new business venture.

A few months later, a group of Polish researchers dissecting the brains of 102 recently deceased cadavers found the more toxoplasma DNA in one's brain, the more likely they had taken a big risk and died because of it.

"T. gondii may contribute to hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide, including deaths in road accidents, accidents at work and suicides," concluded the paper.

The idea that tiny organisms at a massive scale are controlling our minds has provided thought-provoking fodder for several media outlets over the years. Despite several studies on toxoplasma, Lafferty and other scientists interviewed for this story warn that more work needs to be done to understand the extent to which the parasite is manipulating human behaviour.

"All the stuff we have on humans are basically statistical associations, which we need to take with a grain of salt," said Lafferty. "However, they are fairly consistent with well-controlled experimental studies in rodents."

PUPPET-MASTERS AT WORK

The body snatchers of the animal world, parasites are known for bending the minds of their hosts. A famous "zombie-ant fungus" drops toxic spores from the canopy onto a carpenter ant's head in the Brazilian Amazon. The infection causes the ant to wander onto a leaf vine, locking its mandibles to the plant in a final act. Now dead, the fungus sprouts from the ant's head and drops more spores onto the rest of the colony below, completing its life cycle.

While toxoplasma doesn't explode from a cat's head when it's ready to move on, some researchers believe T. gondii also evolved in the Amazon before making its debut on the world stage.

A cat's intestine is the only place it can multiply, so to get back and complete its life-cycle, it hijacks the behaviour of feline prey.

Early studies found rats infected with toxoplasma had their innate aversion to cats turn into a fatal attraction. The more likely a cat eats an infected rat, the more likely toxoplasma will make it into the feline's feces and spread back into the environment. Others have found toxoplasma infected chimpanzees are drawn toward leopard urine in a morbid attraction.

Because cats rarely eat people, T. gondii usually hits a reproductive brick wall when it infects humans. But that doesn't stop it from influencing our behaviour years after initial infection.

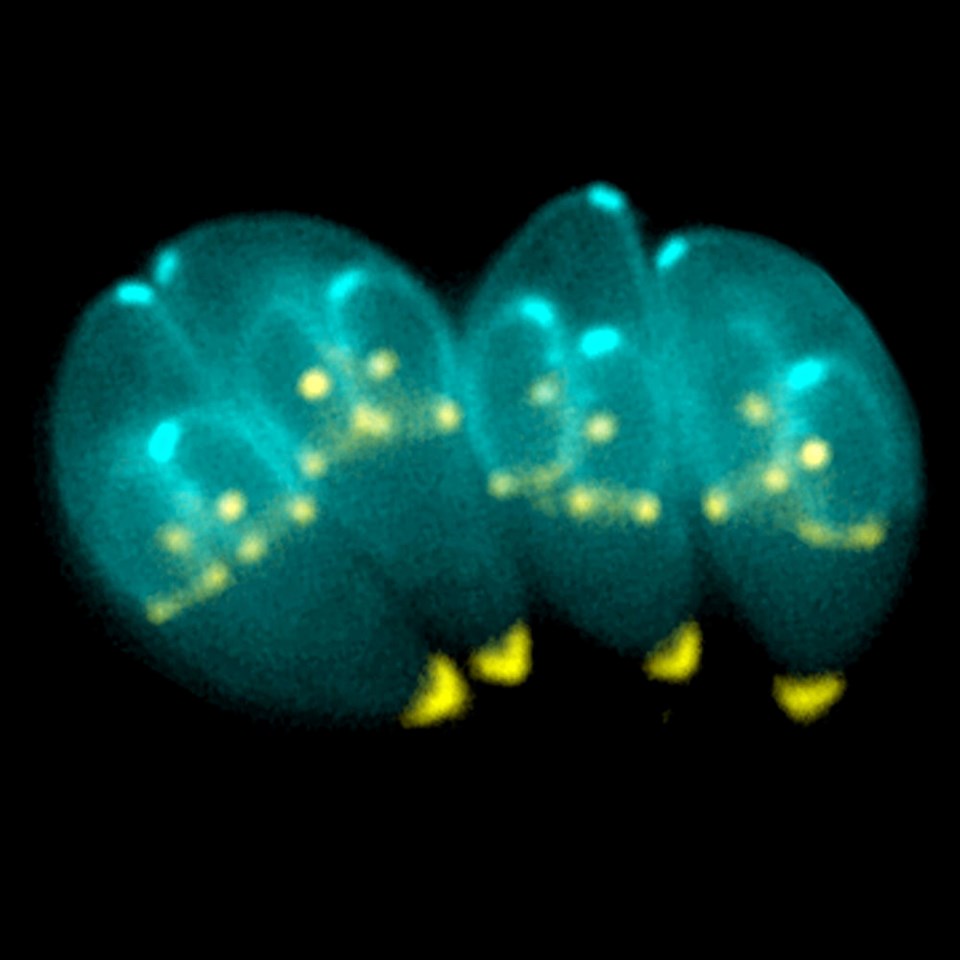

The parasite creates tiny scars in the brain, embedding itself in cysts where it will lie dormant. When the individual has been weakened by disease or age, they can burst open, releasing the parasite and re-surface symptoms years after the initial infection.

For decades, scientists have been building a body of evidence that suggests those tiny scars could be contributing to a range of human diseases. Beyond mind-control, latent toxoplasmosis has been associated with mental disorders like schizophrenia and Alzheimer's, as well as epilepsy, autism, cognitive and vision deficits, cancers, and increased severity of other diseases like HIV.

GLOBAL INFECTION RATES SHIFTING

Despite its staggering global infection rate, toxoplasmosis in humans appears to be on the decline, says Lafferty. That's largely due to rising standards in hygiene, food production and water treatment, as well as recognition among many pet owners that cats live a healthier and longer life inside.

But according to recent research out of the University of British Columbia, those global declines could be masking some important regional differences.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B last month, examined over 45,000 cases of toxoplasmosis in more than 200 wild mammals at over 1,000 locations across the globe.

Layering positive toxoplasmosis cases onto maps showing human density, the researchers found 19 per cent of all animals tested positive for toxoplasma. Higher rates of infection were found in wildlife near urban centres, where domestic cat populations climb and the filtering effects of wetlands, damaged and destroyed by urbanization, decline.

In one example, grizzly bears were found to have lower toxoplasma infection rates than their black bear cousins, who more often live near human population centres, said lead author Amy Wilson, a UBC forestry professor and practicing veterinarian in Vancouver.

Some of the most significant increases were found in aquatic ecosystems, where contaminated storm runoff can carry the toxoplasma eggs into the bodies of whales, fish and sea otters.

"Habitat conservation is not just a concept. It's also a public health intervention," Wilson said. "People need to understand that there are services that these ecosystems provide — with climate change its carbon sequestration, but there's also pathogen filtration."

At the same time, her research suggests turning off the source of toxoplasma will require cat owners to make millions of individual decisions, all landing on "don't let your animals wander freely."

Does that kitten you adopted during the pandemic make you more susceptible to parasitic mind control? No, Wilson tells Glacier Media. If you have an indoor cat, the likelihood of them shedding the pathogen will be very low, especially if they are not killing wild prey and you regularly clean their litter box.

"There can be some simple interventions that we can do here that benefit wildlife and also benefit us for too. It's a shared fate," said Wilson.

CLIMATE CHANGE IS A MIXED FATE

Like any living creature, the spread of toxoplasma is under the influence of global climate patterns. Wilson's study found that the parasite's eggs survived as temperature increased, leading to questions over whether climate change will shift infection levels to new parts of the world.

A separate study in Europe suggested climate change could increase toxoplasmosis infection rates in northern France, Belgium and Great Britain over the coming decades. At the same time, climate change is expected to lead to warmer, drier climes in Southern Europe, making it less hospitable for the parasite.

Could climate change offer toxoplasma a more comfortable niche in Canada? The reality is T. gondii has already made its way from the Amazon to Inuit communities in the Canadian Arctic.

Lafferty says that trend is only likely to continue as pockets of warm, moist conditions migrate across the globe in the coming decades.

"The prediction about toxoplasma, which is true for malaria, is that its ideal distribution is going to shift toward the poles."

On the other hand, if you're home is slated to transform into an arid desert scape, at least you'll have a better shot at avoiding the world's most prolific parasite.

LIVING WITH PARASITES

T. gondii was first discovered in 1908 in a Tunisian lab when two scientists isolated the parasite in a tissue sample from a gundi (hence 'gondii'), a hamster-like African rodent.

It would be another 30 years before it was first found in a human — an infant born by a caesarian in New York City — and not until 1970 when scientists started to understand cats' unique role as the only host that offers the right conditions for the parasite to reproduce sexually.

But toxoplasma has likely been living alongside human populations much longer, itself a startling example of life's ability to adapt.

Today, we know enough about the parasite to tap into some of our worst fears, fears Lafferty says need to be tempered with a sense of wonder.

"It's terrifying to have this parasite in your brain controlling your behaviour," he said. "It gets in our brains and does these subtle things, things that are subtle enough that we can detect them in humans, and we can demonstrate them in experiments with rodents."

A fascinating way to look at the parasite, says Lafferty, is to understand that humans and toxoplasma have been interconnected for a long time — so long it may be hard to define where we end and where the pathogen begins.

Lafferty says we've failed as a society to have a conversation about toxoplasma, a parasite affecting a high percentage of the population and whose latent effects are rarely talked about in public health.

"If I told you you could take a drug that would cure you of it, would you take it? Would you give up that part of your personality that you'd become accustomed to?" Lafferty said.

"You live an interesting life, and maybe part of that interesting life is the fact that you're infected with toxoplasma."