An analysis of almost 250 marine heat waves has found the impacts on bottom-dwelling fish were “often minimal” and found no evidence extreme heat events had driven colder water fish toward the poles.

Juliano Palacios-Abrantes, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of British Columbia’s Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, said the findings counter previous research into the effects of heat waves on marine life.

Past studies have linked prolonged periods of anomalously warm ocean temperatures to widespread coral bleaching and die-offs of reef fishes and kelp forests. In other cases, evidence has been found that shows marine heat waves can displace species hundreds of kilometres and abruptly impact everything from plankton (the building block of the ocean’s food chain) to larger commercially important species.

But the latest study, found fish dwelling closer to the sea bottom — including flounder, halibut, rockfish and all five species of Pacific salmon — were surprisingly resilient to rising temperatures.

“We were not able to find any overall pattern that we can statistically say, ‘OK, when you have a marine heat wave, you will have overall negative impact on fish,” said Palacios-Abrantes, who co-authored the report.

The study, published this week in the journal Nature, involved more than a dozen researchers from multiple countries. The team analyzed 248 sea-bottom heat waves from 1993 to 2019. The data set, one of the most comprehensive available to scientists, included over 80,000 samples taken along the continental shelves of North America and Europe.

William Cheung, director of UBC’s Ocean Sustainability and Global Change Institute and another co-author on the study, said the results were surprising, and showed the impacts of heat waves on fish could be both more complex and more “sporadic” than once thought.

“In some cases, it has big impacts,” added Cheung.

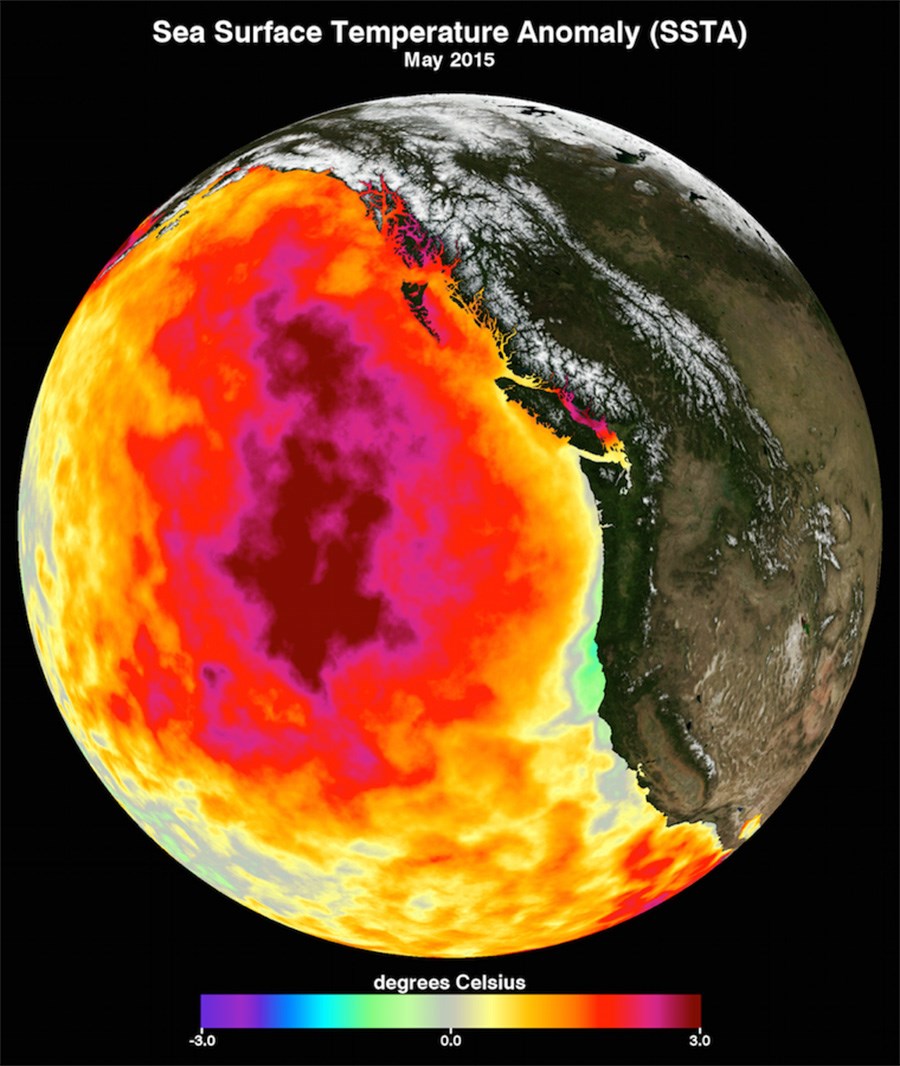

He pointed to a powerful marine heat wave known as “The Blob” which between 2014 to 2016 led to a 22 per cent loss in biomass off the coast of B.C. and Alaska.

But such events “were the exception, not the rule,” concluded the authors.

Bottom fish tough but not invincible to heat

It’s not clear how the broad swath of bottom-fish populations were tougher than previously thought and how they came through so many heat waves relatively intact.

One possibility, suggested the study's authors, is that the fish are diving down to cooler depths or escaping laterally into nearby cooler waters in what appears to be a successful search for “climate refugia.”

“When ‘The Blob’ happened in the North Pacific, you have reports of species being like kilometres away from where they were ever seen before,” said Palacios-Abrantes.

At the same time, Palacios-Abrantes said it could be that a lot of previous studies looking at the impacts of marine heat waves focused on the extremes.

Palacios-Abrantes compared the ability of bottom fish to endure heat waves like the barely perceptible small tremors in his hometown of Mexico City.

“We only really notice the ones that are like beyond like six points on the Richter scale,” he said. “So we always associate earthquakes with extreme danger.”

Taken together, the ability of the bottom fish to get through a variety of heat waves unscathed as populations shows “there is some light of hope,” he said.

Tipping point could be around the corner

The researchers say their study needs to be expanded to the planet’s southern waters, as they were largely left out of the analysis and could help confirm or challenge what was found in the waters surrounding North America and Europe.

At the same time, both Cheung and Palacios-Abrantes said their historical analysis does not reflect how fish will survive future heat waves, which are expected to be more frequent, longer and more powerful amid a rise in human-driven climate change.

Species living closer to the surface — including coral reefs and the ecosystems they support — were not included in the study, and Palacios-Abrantes says there’s plenty of other studies that show they are already suffering from rising ocean temperatures.

With time, he said, deeper-dwelling fish might be next.

“If we don't reduce emissions and marine heat waves become more intense, or more frequent or longer, then that resilience, that natural capacity of the system to resist to perturbations might not be enough,” said Palacios-Abrantes.

“When do we reach a tipping point? That we don’t know and we don’t want to get there.”