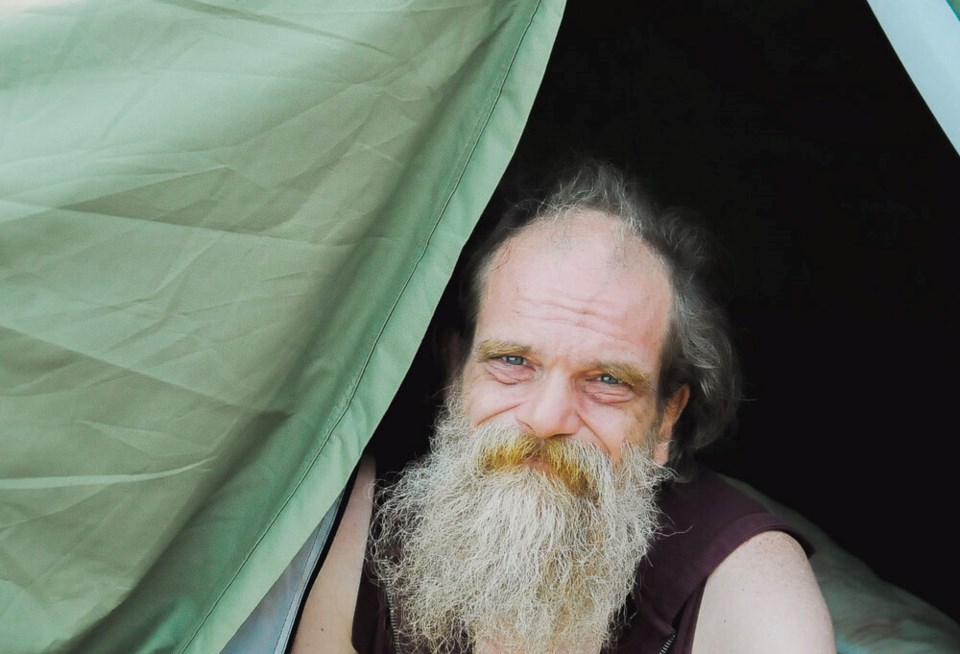

Under the heat dome, Vanessa Csurbi measured survival in the spaces between shade and water.

Fifty metres to the women’s shelter for a cold bottle.

A hundred metres to the volunteers handing out Freezies.

As the temperature soared past 40 C, Csurbi would tuck herself into the lee of a building with her dog, searching for relief and fighting back dizziness. Concrete everywhere.

“I would move around to different spots. I'd soak myself at the different water stations,” she remembers. “You don’t have these big, lush trees.”

“If you're homeless and you're down in the Downtown Eastside, it's really, really hot.”

Vancouver is no Montreal or Toronto. Summertime temperatures are usually buffered by the cooling effects of the Pacific Ocean, and the city rarely faces the vicious heat waves of other North American cities.

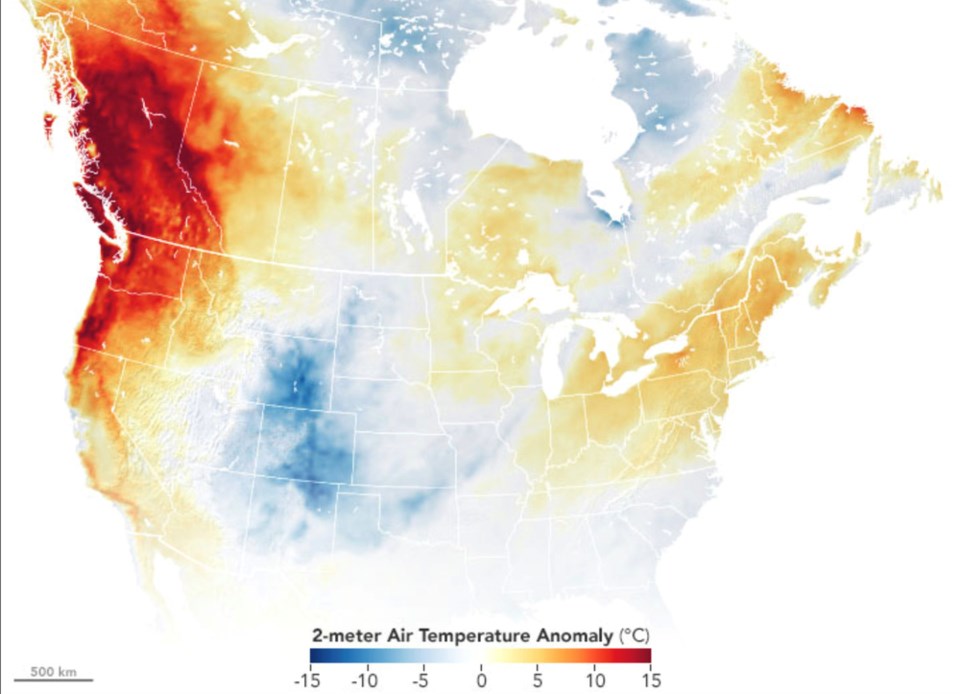

That respite took a deadly turn at the end of June when a one-in-a-thousand-year slab of high pressure roasted British Columbia, shattering all-time temperature records and leading to at least 569 deaths.

By the time the ambulance and fire truck sirens waned, it became clear death hit B.C.’s biggest cities hardest, where the amplifying effects of a concrete jungle create a notorious “urban heat island effect.”

On a hot day, dark-coloured surfaces like roads and rooftops absorb and trap heat, releasing it back into the air and creating “islands” of elevated temperatures.

Those temperatures tend to get worse late into the day. After sunset, the respite the body needs to recover in a heat wave gets cancelled out.

A well-placed tree, however, can save lives.

In neighbourhoods with dense tree cover, modelling suggests that a pedestrian standing directly under a tree canopy would experience temperature reductions upwards of 17 C. Direct shading matters, but so does the cooling effect of water passing through a tree’s limbs and leaves and evaporating into the air. Increase the canopy, and trees can drive temperatures down across an entire neighbourhood.

Who the heat wave killed and how to best save lives in the future is not yet clear. The BC Coroners Service continues to investigate the circumstances around each death, and Vancouver city council is lobbying for more ambulance stations and access to air conditioning for some of the city’s most vulnerable.

What is clear, says the BC Centre for Disease Control’s scientific director Dr. Sarah Henderson, is more people died of heat in Vancouver, Burnaby and New Westminster, in low-income areas, where people lived alone and with little green space.

"This was the most deadly weather event in Canadian history, probably by a factor of about three," says Henderson.

Unreleased data collected by Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) and seen by Glacier Media indicates the working-class neighbourhoods of South Vancouver saw double the number of heat-related hospitalizations compared to the more affluent neighbourhoods of Point Grey, Dunbar and Shaughnessy.

On Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, Canada’s poorest neighbourhood, hospitalizations tripled, with more people admitted to emergency rooms due to heat than anywhere else in the city.

Pre-existing medical conditions, age, as well as drug and alcohol use all make the neighbourhood especially vulnerable to heat. Many residents don’t have the resources to seek shelter in an air-conditioned hotel, and many like Csurbi face extreme heat with little more than an alcove for cover.

Hospitalizations peaked in the hottest, least green parts of the city. Affluent, tree-rich neighbourhoods on the west side of the city, experienced relatively cooler temperatures under the heat dome. But in South Vancouver and the Downtown Eastside, where trees are scarce, temperatures soared.

It’s a pattern of inequality found across Canada’s biggest cities, with shade deficits affecting poorer neighbourhoods in Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa and Quebec.

The fallout is only expected to get worse. In the weeks following the heat dome, climate scientists found the heat wave was made 150 times more likely due to human-caused climate change. By the 2040s, such events could occur every five to 10 years.

In the fight against extreme heat, stark policy choices lie ahead. But according to dozens of residents and experts interviewed for this story, there is one clear fix that cannot wait: more trees.

RAZING A FOREST, BUILDING A CITY

When Captain George Vancouver sailed into Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish territory, the land north of the Fraser River delta was covered in a patchwork of shade filtered through stands of Douglas fir and Western Red cedar.

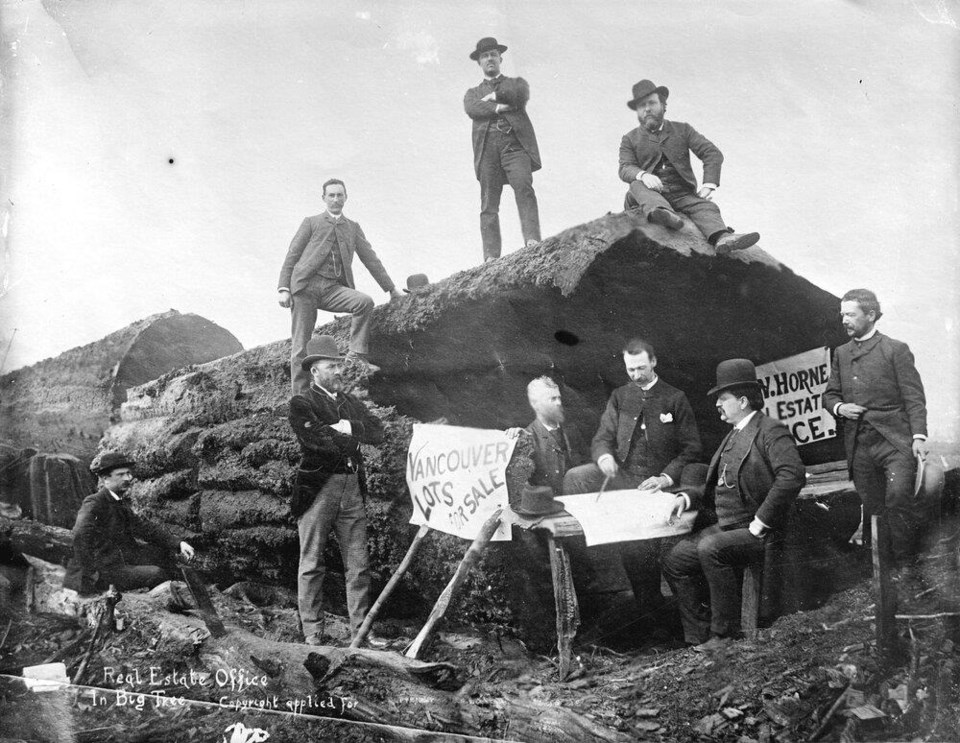

Though famous for its arboreal giants, razing the forests of Vancouver — indeed much of B.C. — built and bankrolled its expansion.

By the time the city incorporated in 1886, Vancouverites were said to celebrate every time a soaring cedar was felled to make way for a growing city. In one sign of the urbanization to come, a group of realtors turned a downed old-growth tree into an office near Georgia and Granville Street — all in the name of advertising.

Trees died for money, but for decades a fraction survived in the city that money built.

It wasn’t until the early 1990s when a plan to sustain Vancouver’s urban forest took shape.

At first, efforts to increase the city’s tree canopy yielded underwhelming results. Light Detection and Ranging, or LiDAR technology — which creates 3D elevation maps by bouncing a laser from an aircraft to the ground — found Vancouver’s overall canopy had climbed by a mere one per cent between 1995 and 2013.

That changed in 2011 with the passing of the “Greenest City Action Plan,” which among other goals, set to plant 150,000 new trees by 2020.

The plan flooded many existing parks and empty boulevards with trees. The city bought small chunks of land, turning street right-of-ways into “pocket parks.”

Roughly 37 per cent of Vancouver’s tree canopy sits on private land. But for decades these trees were disappearing. Between 1996 and 2013, the city lost an estimated 50,000 trees, roughly half of those felled under a bylaw exemption that allowed residents to remove one tree a year.

In 2014, the city responded, banning residents from cutting down mature healthy trees on their property. At the same time, the city subsidized an annual tree sale to help homeowners repopulate their backyards with saplings, and education programs focused on convincing residents trees can not only improve a neighbourhood’s aesthetics and boost urban biodiversity, but also act as a thermal buffer during extreme heat and cold.

Momentum built slowly. Climbing from under 10,000 new trees in the first four years to over 21,000 in 2016. In December 2020, Vancouver surpassed its decade-long, 150,000-tree goal after arborists planted a grove of Douglas fir at a park next to the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge.

Today, many easy-to-plant areas have become saturated, and in parks, the city’s plan rests on keeping what’s already planted alive.

“I think it’s safe to say in the 150,000-tree goal, the lowest hanging fruit was targeted,” says Joe McLeod, city arborist and supervisor of urban forestry for Vancouver.

By 2018 — the last year public data is available — Vancouver’s tree canopy climbed to cover 23 per cent of the city, up two per cent from 2013. And in late 2020, city council approved a new city-wide target of 30 per cent canopy cover by 2050.

To get there, McLeod says Vancouver needs to sort out its tree species supply chain so nurseries have time to rear saplings slated for planting over the next decade. Having a mix of trees that can weather climate change is just part of the equation.

“We’re going to have to seek some of these harder-to-plant locations in paved areas. It’s higher cost per planting spot,” says McLeod. “It’s a lot of people, it’s a lot of money, but dollar for dollar, it’s an investment in the city’s future.”

As the city continues to grow, so too does the endless tension between new developments and saving what trees are left.

“This is throughout the world. In most urban areas, the tree canopy is declining,” says Michael Brauer, a UBC researcher who studies the link between the built environment and public health.

“Right now, it’s an uphill battle.”

CLOSING THE GREEN DIVIDE

In a city constantly seeking to reinvent itself, bricks and hardscape surfaces can add charm to old neighbourhoods like the Strathcona. They also make planting trees a daunting task, says McLeod.

Creating a street-side canvas to plant a tree means arborists need to remove entire sections of sidewalk to get to the often poor soils underneath. It's a problem facing municipalities across Metro Vancouver, each grappling with ways to stem an overwhelming decline in tree canopy cover.

“It’s working against urban engineering,” says McLeod. “It’s excruciatingly hard.”

Across the city, McLeod’s team is racing to counteract canopy loss as the city tears up ground to replace its aging sewer system. Large building developments mean large floor plates, leaving little porous ground to grow trees. And in the case of mega-projects, like the Broadway Corridor SkyTrain extension, the city will lose a big chunk of the canopy in one fell swoop.

“It’s a noble pursuit to improve transit along there, but we need to replace those trees,” he says.

According to the City of Vancouver, 92 per cent of residents are within a five-minute walk of green space. Yet the quality of those green spaces, as well as their cooling potential, masks huge inequities.

In the affluent neighbourhoods of Vancouver’s west side, tree canopy cover can rise to 28 per cent, more than four and a half times that of Strathcona, where the sun beats unimpeded on residents of the Downtown Eastside.

One day in August, it shone on Diane Brisson as she dashed under a temporary misting station to temper the 36-degree heat.

“I can’t bear my room,” says the Indigenous woman, originally from Ontario. “I’m not used to heat like this anymore.”

While Indigenous people make up two per cent of the general population, they account for 31 per cent of the Downtown Eastside’s total population and 39 per cent of the city’s homeless population. Black people, meanwhile, are 3.7 times more likely to experience homelessness, according to Metro Vancouver’s 2020 homeless count.

Such numbers prop up what many researchers and advocates decry as “climate racism,” where stresses from heat waves and other extreme weather hit racialized communities hardest.

But death by heat is not a problem relegated to the homeless or poorly housed. People living alone with limited support are seen to be just as vulnerable as those living on a sidewalk under the sun.

“ER visits are part of it. But most people who died never got to an emergency room. They were found at home,” says Dr. Tom Kosatsky, medical director of environmental health for the BC Centre for Disease Control.

“You really have to look after elderly people, people with chronic conditions, people who have chronic alcohol issues. Those people are really the ones who need help.”

Though less intense than in the Downtown Eastside, health authority data also shows spikes in emergency room visits for heat-related illness in the city’s downtown core and the neighbourhoods of southeast Vancouver, where older adults, impermeable concrete surfaces and low canopy cover often converge with higher temperatures.

In July, B.C.’s chief coroner Lisa Lapointe said her agency is reviewing just how many people died alone in sealed apartments. Coroners, said Lapointe, are “paying close attention to glass buildings… really not the best type of building when you’re looking at climate warming.”

Upper-floor residents of the city’s Single Resident Occupancy (SRO) hotels also face an elevated risk. Built over 100 years ago for seasonal workers coming into town from logging camps around the province, SROs make up an important part of the Downtown Eastside’s affordable housing stock.

But many units are poorly ventilated and Downtown Eastside SRO Collaborative advocate Wendy Pederson says she knows of at least one tenant who died in late June — a small glimpse, she says, of the heat death that gripped the neighbourhood.

Pederson is organizing tenants to do room checks, fundraise to buy fans and create a shuttle system to bus people with limited mobility to cooling centres. Such measures have proven to work in places like New York City, says Brauer. But finding money to adapt to rising temperatures means competing with multiple crises, from a poisoned drug supply to a long battle against COVID-19.

On the south side of the city, neighbourhoods like Marpole face the legacy of a forest diversity program that prioritized aesthetics over function, which has led to planting smaller trees like purple plum, dogwoods and birches. Those trees never survive for long and don’t reduce neighbourhood temperatures like the tree-lined avenues of Shaughnessy, Dunbar or West Point Grey, according to McLeod.

For Marpole resident Leah Ever, summer temperatures have made life tough since she moved into her aging four-storey walkup 15 years ago.

“It wasn’t until the heat wave that I understood what unbearable was,” she says.

To cope with the 40 C-plus temperatures, Ever attached a hose to her shower and ran it up to the rooftop where it sent a cascade of water over an umbrella.

“I had the sensation of rain,” she says. “I’m lucky I’m on a roof in that way because I could do that.”

Others are not so fortunate. Driving down neighbourhood temperatures would mean swapping out smaller trees for more robust species at an immense scale. Such an undertaking will delay the canopy’s shading potential for decades while new species mature.

Planting already matured trees is rarely an option. The city almost always plants trees with trunks roughly seven centimetres across. The girth is manageable for two people to lift; trees of that size and age also strike an ideal balance between having a good chance of survival and having a root bulb small enough to fit into narrow city boulevards.

“Our boulevards are only about one metre in width,” says McLeod. “Our built spaces are really limiting us.”

It’s a reality residents like Ever say creates a dangerous divide between those neighbourhoods fortunate to have a legacy of shade and those without.

“I didn’t really choose to live in this neighbourhood. It was out of necessity,” she says.

HEAT KILLS TREES TOO

The dash to plant new trees comes as city forestry staff race to save its existing canopy.

McLeod says the heat wave had a devastating impact, triggering a big increase in “sudden branch drop,” where the limbs of seemingly healthy trees fall to the ground in catastrophic failure.

Vancouver hired outside contractors to keep up with the watering. And as drought spread across the region in July, the city deployed water cannons and called on residents to help keep trees alive one bucket at a time.

“We’ve been running crews overtime,” says McLeod. “We’re probably going to see a significant amount of loss.”

From vandalism and car accidents to pests, pathogens and ornamental lighting, McLeod says “there’s a million factors that are working against our trees.”

But it’s a changing climate that has the arborist most concerned.

McLeod and his team are starting to imagine a future forest that could increasingly look like those of Northern California. He’s also not ready to give up on the iconic Western Red Cedar, and is looking to source saplings from the drier areas of eastern Vancouver Island, where hardy varieties are more drought-resistant.

Creating a new planting pallet will require significant investment, says McLeod, both to retain already planted trees and hit future targets.

“It snowballs. If it gets hotter, it gets harder to grow trees; if it gets harder to grow trees, it gets hotter,” he says.

“This year has been the most extreme yet, but these extremes are just going to become more and more.”

'A LOT OF COMMUNITY SUPPORT'

As the thermometer rose in the last week of June, paramedics recounted scenes of chaos in hospital emergency rooms across Metro Vancouver.

One BC Ambulance paramedic tells Glacier Media he went to five cardiac arrests in a row, only to find patients dead when they arrived.

In several cases, emergency personnel say they found people unable to access cooling centres because of mobility problems. Others on the street were found collapsed due to a combination of heat illness and a drug overdose.

“Many remained laying in the sun for hours,” says one paramedic, whose name Glacier Media is not publishing for fear of workplace backlash.

Hospitals across the Lower Mainland were swamped with scenes emergency personnel say still haunt them.

“I didn’t know what I was walking into when I walked into Surrey [Memorial] Hospital and saw dead people on the floor, family showing up with dead people in their cars,” says a paramedic.

In a parking lot next to the Downtown Eastside’s towering Arco Hotel, the Overdose Prevention Society saw visits spike by 25 per cent during the June heat wave, rising to over 900 a day.

Behind its plywood walls, dozens of canopies cover picnic tables, where drug users can sit and get access to clean needles and a sliver of shade.

“You could see that people were suffering… high, nodding out and not coming around as quickly as they normally would,” says site manager Amy Evans.

Such sites have been an important bulwark against a poisoned drug supply that has taken the lives of over 2,300 people in Vancouver since 2011 — many of them Downtown Eastside residents.

Age and pre-existing medical conditions, like heart disease or high blood pressure, increase health risks when a heat wave hits. But so does recreational drug use — cocaine and amphetamines can interfere with the human body’s ability to compensate for the heat and alcohol only accelerates dehydration.

The June heat was so extreme, Evans says hundreds of people came not to use drugs, but for water, medical attention and a piece of shade.

In about a dozen extreme cases of heat exhaustion, ambulances never showed up, so staff put people into an air-conditioned shipping container usually reserved as an office. Where the city’s tree canopy and emergency services fell short, people stepped in to fill a hole left empty in other parts of the city.

“The Downtown Eastside has been kind of ground zero for that — a lot of community support,” says Brauer. “There’s other places that need that.”

Evans says the experience has broadened her definition of harm reduction — an approach seeking to reverse overdoses and help people with addiction without calling for abstinence.

“It was really drug-focused,” Evans says of the society’s work to save lives. “Now, I see things in a bigger picture: giving out water on a hot day is absolutely top of the line.”

A WIDER CITY TRANSFORMATION

As Vancouver aims to boost canopy cover to 30 per cent by 2050, it’s also targeting some of its neighbourhoods long neglected in its race to become the “greenest city.”

In Marpole and the Downtown Eastside, Vancouver plans to accelerate tree planting to double street tree density in below-average blocks by 2030.

It’s all part of a holistic approach to climate-proof the city against increasingly hot, dry summers and winters dominated by extreme rain. At the broadest scale, that means reorienting the city away from gasoline-powered cars and toward public transportation, pedestrian-friendly avenues and trees.

Vancouver has also set an ambitious target to ramp up green infrastructure projects, like green-scaped rooftops and rain gardens.

The idea is to simulate a natural water cycle wiped out from decades of city building. Positive spin-offs include flood protection, cleaning tainted rainwater and counteracting urban heat islands — not to mention helping the city meet its target to cut carbon dioxide emissions by half over the next decade.

Trees protect against more than heat. Studies have shown higher concentration of neighbourhood trees leads to a drop in everything from dementia and diabetes to heart diseases and chronic depression.

“Across Canada, we see that in greener neighbourhoods, people live longer. You see this really strong effect,” says Brauer.

But since the heat wave, local politicians have raised concerns that current greening projects could risk adding another dimension to the inequality already creating huge gaps between Vancouver’s rich and poor.

In July, the City of Vancouver passed a motion to address growing pressures on ambulance stations and a rising sense of inequality in the face of climate change.

“As I sat in front of a fan with a frozen tea towel around my shoulders, I thought of the folks in the SROs with the high, hot floors and no fan or freezer,” says Coun. Jean Swanson. “It’s definitely a rich-poor issue.”

Meanwhile, the BC Coroners Service has yet to release neighbourhood-level data on where the 569 victims of the heat wave died, and how factors such as building design, lack of air conditioning and pre-existing conditions killed.

Until the city and provincial government act on that data, Evans and her group of volunteers continue to offer shade, hand out water and stuff people into air-conditioned sea cans.

“We’re a stop-gap until the trees grow,” she says.

It's that kind of support Brauer says government and community organizations need to scale up across the region before the next devastating heat wave.

For homeless people like Csurbi, any improved access to shade and water is welcome.

By mid-August, sirens lit up downtown as the summer’s third heat wave enveloped the city. Those sounds were a distant echo at the Downtown Eastside’s Crab Park at Portside, where Csurbi took her dog for a swim and sought respite from the heat.

Next to a growing homeless encampment, Csurbi picked her way among 215 cedar saplings, clearing the weeds. A group of guerrilla gardeners planted the young trees three weeks before the heat wave to commemorate the discovery of the children’s remains found at the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Their survival was tested amid the roar of helicopters, seaplanes and loading ships, all during the city's second hottest summer on record.

Csurbi walked through the heat to the largely shadeless park unaware air-conditioned buildings had been set up for people like her. When asked if she would use such services, she hesitated.

“I'm a drug addict. It's hard going to just any old place because people are really judgmental,” she says. “I'd prefer to be outside… somewhere with big shady trees.”

June’s deadly heat haunts Csurbi. She thinks of the 18 people police told her died in one day in her neighbourhood.

But where data singles out the Downtown Eastside as one of the most vulnerable neighbourhoods to extreme heat, Csurbi sees something else.

“Families with their kids were just walking down Hastings [Street] where there's all these drug addicts and needles and you name it — handing out food and water. I mean, that's awesome. People have to come together.”

***

Stefan Labbé is a solutions journalist covering how people are responding to problems linked to climate change. Have a story idea? Get in touch. Email [email protected].

This article was produced by Glacier Media. Reporting for the story was supported by a bursary from Journalists for Human Rights and the Solutions Journalism Network, all made possible with funding from the McConnell Foundation.

Data for the tree canopy graphic was drawn from research conducted by Mehdi Aminipouri at Simon Fraser University.

The maps in this story were prepared by the environmental consulting firm Diamond Head Consulting Ltd. in partnership with Glacier Media.

Heat sensitivity and adaptive capacity maps were generated using data from Vancouver Coastal Health's Climate Change and Health Adaptation Team in partnership with a UBC research team investigating neighbourhood vulnerabilities to extreme heat, flooding and air pollution.

Data for the tree canopy cover and impervious surfaces maps were summarized by census dissemination block using data generated from the 2014 Land Cover Classification 5m, hybrid, retrieved from Metro Vancouver's Open Data catalogue.

Land surface temperatures were pulled from the Landsat-8 image captured June 30, 2021, at 7 p.m., courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.