A heat wave sweeping through the lives of millions of people across Western Canada and the U.S. Northwest is being made up to five times more likely due to climate change, real-time modelling indicates.

Records across British Columbia are expected to fall this weekend, with daytime temperature highs expected to climb 18 C above seasonal averages, according to forecasts by Environment Canada meteorologists. By Sunday, temperatures could reach levels typically seen in July and August.

At least one police detachment in the province said Friday they might activate an extreme heat response plan and conduct extra patrols. The heat has also prompted experts from the BC Centre for Disease Control to warn vulnerable people to take extra care.

For one group of climate scientists, the fingerprints of climate change are unmistakable.

“This is what climate change looks like — these kinds of unusual conditions early in the season, popping up suddenly like,” said Andrew Pershing, director of climate science at the U.S. research group Climate Central.

“It’s really going to hit a peak this weekend.”

Using a pool of historical weather data, Pershing and his team use a peer-reviewed process that compares observed temperature data with models that estimate how weather would behave with and without human-caused climate change.

That’s all combined into a public facing Climate Shift Index (CSI), a rapid attribution tool that allows anyone with an internet connection to see the likelihood climate change is influencing current temperature patterns in their corner of the world.

“What we're doing is looking at how often a particular temperature we expect to occur in today's climate with about close to 1.3 degrees Celsius of global warming. And then we contrast that to hypothetical climate that didn't have global warming,” said Pershing.

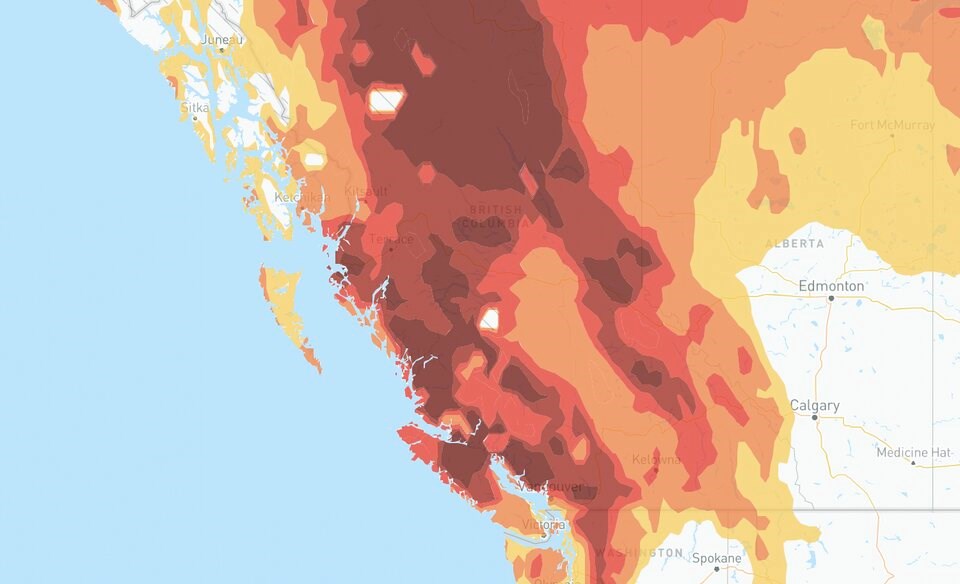

The result is an ever-changing heat map of the planet, shaded with a five-step scale. At zero, the influence of climate change on weather conditions, such as a daily high or low temperature, is not detectable. At this point on the scale, the prevailing weather is as likely to proceed with or without the effects of climate change.

A CSI of +1 indicates climate change has made weather 1.5 times as likely; at +2, a strong effect from climate change has made weather twice as likely; at +3, a very strong climate fingerprint has made the prevailing weather three times as likely; and at +4, weather conditions have been made four times as likely, or “extremely rare without climate change.”

At +5, an “exceptional” climate change signal indicates weather conditions have been made at least five times more likely, “potentially far more,” states Climate Central’s CSI scale.

As of Friday morning, their heat map showed dark red enveloping much of B.C. and a huge swath of Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Pershing said in many areas across Canada, the likelihood climate change is impacting the heat will be so strong, their scale won’t capture it.

“It’s a big red blob,” Pershing said. “I think over this region, especially in Canada, you're gonna get a lot of areas that are maxing out at that level five.”

With such a strong signal from climate change, Pershing says his group is already having to readjust the scale. That’s especially true at sea, where the Climate Central team of researchers is developing a similar tool to measure climate’s impact on ocean heat waves — something that has a strong influence on hurricanes, nor'easter storms and atmospheric rivers.

“The attributable signal of climate change is so strong in the ocean that it really sort of breaks our minus-five-to-five scale,” he said. “We have to totally rethink it…”

Pershing says that in North America and Europe, pulses of heat — like the one this weekend — have been made more likely by climate change.

Elsewhere in the world, however, climate change’s signal has already permanently altered daily weather, he adds. He points to places like Africa, South America and Southeast Asia.

“That's what we need to prepare for. Those are the stakes. That's what we get to avoid if we can reduce our carbon emissions,” he said.