In Gaines County, Texas, where a measles outbreak has killed one six-year-old and one adult, the measles vaccination rate among kindergarteners is just 82 per cent, according to reporting by The Atlantic.

That’s a higher measles vaccination rate than children have here in B.C.

Just under 82 per cent of two-year-olds have gotten one dose of the measles, mumps and rubella, or MMR, vaccine, and around 72 per cent of seven-year-olds have gotten both doses, according to the B.C. Childhood Immunization Coverage Dashboard’s 2023 data, which is the most recent data year available.

One dose of the vaccine offers between 85 and 95 per cent protection, and two doses offer 97 to 100 per cent protection from getting sick if exposed, said Dr. Jia Hu, interim medical director of the BC Centre for Disease Control’s immunization programs and vaccine-preventable diseases team.

Measles is one of the most infectious diseases on Earth. An infected person can walk through a room and up to two hours later a healthy person can walk through the same room and get sick, just by breathing the lingering air.

The disease can cause brain swelling, leading to seizures, deafness or brain damage, and kills about one in every 3,000 people, according to HealthLinkBC. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention gives a grimmer estimate, reporting that one in four cases of measles requires hospitalization and one in 1,000 cases results in death.

Unvaccinated people who survive a measles infection are at a radically higher risk of dying from another illness in the years after the infection. Measles can wipe out 11 to 73 per cent of an unvaccinated person’s antibodies, meaning their immune system forgets how to fight off pathogens it previously defeated.

Measles cases are on the rise in North America, which increases unvaccinated people’s risk of being exposed to the disease, said Caroline Colijn, a mathematician and infectious disease modeller at Simon Fraser University. Colijn holds a Canada 150 Research Chair in mathematics for evolution, infection and public health.

Measles immunity varies across the province. The B.C. Childhood Immunization Coverage Dashboard shows some of the lowest vaccination rates in the province are in the Northwest Health Service Delivery Area (stretching from Chetwynd to Fort Nelson) with a 74 per cent MMR vaccination rate for two-year-olds, and the Kootenay Boundary Health Service Delivery Area (stretching from Kettle Valley to Kootenay Lake) with a 62 per cent vaccination rate for seven-year-olds.

“You can have outbreaks with those kinds of rates,” Colijn said.

Assuming there was about 87 per cent immunity to measles evenly spread across the province, B.C. could have an outbreak of around 100 cases that lasts over two months, estimated Jennifer McNichol, a PhD student in applied mathematics at SFU working with Colijn.

Those numbers would depend on “how strong the responses of the community and how much effort is put into isolating people who’ve been exposed,” she said.

Colijn and McNichol have been running mathematical models to simulate what measles outbreaks could look like in Canada.

“Measles can spread like wildfire in communities with low vaccination rates, especially when unvaccinated individuals have high rates of contact with each other,” Colijn said.

In their modelling, communities with vaccination rates of around 60 per cent would see between half and one-third of all unvaccinated people getting sick, even with strong interventions like isolation, McNichol said.

For measles, “herd immunity” requires 95 per cent of the population to be immune either through previous infection or through two doses of the vaccine. Herd immunity means that if one person is infected in a community, the virus won’t be able to spread to any other people.

Vaccination rates between 80 and 85 per cent is “when we start to worry more,” she added. “The lower the coverage is, the more chance there is that measles infects the next person and the higher chance an outbreak will take off.”

BCCDC urges residents to check their vaccination status

As of Tuesday the Texas Department of State Health Services was reporting 223 cases of measles, of which 29 patients had to be hospitalized and at least 80 patients had not been vaccinated, and five patients had only one dose of the vaccine. The rest of the patients had an “unknown” vaccination status.

The child in Texas and adult in New Mexico killed by measles infections were both unvaccinated.

There’s also a massive measles outbreak here in Canada.

As of March 6 there were at least 224 cases of measles in Ontario with the majority of people getting sick being unvaccinated children, according to reporting by CBC.

As of March 7 there were 31 confirmed cases of measles in Quebec, according to provincial reporting.

Both Ontario and Quebec are sharing lists of places where more people may have been exposed to the virus.

Hu of the BCCDC said he is “quite worried” about a measles outbreak in B.C.

Measles vaccines aren’t mandatory to go to school in B.C. but are offered for free to people of all ages in the province, Hu said. Children are recommended to get vaccinated at 12 months and again at between four and six years old as they enter school.

Hu encouraged everyone to check their immunization status and to get a free vaccine if they haven’t had two doses or survived a measles infection.

It’s up to every individual or family to keep track of what immunizations a person or child has or has not gotten, Hu said.

When a child or adult gets a vaccination, they used to be given a piece of paper that said what vaccine they got and when, which they could add to their at-home vaccination record.

The first thing to do is to see if you can track down your vaccination records and compare it with B.C.’s recommended list of childhood vaccines, Hu said. This is also a good practice for parents of young children whose immunization schedule may have been thrown off by the COVID-19 pandemic health-care disruptions.

If you do not have this vaccination record, you can check your immunization records through Health Gateway, which shows records in the Provincial Immunization Registry, including immunizations given at public health clinics and pharmacies in B.C.

However, the Provincial Immunization Registry is an incomplete data set. Immunization records for school-aged kids started being added only in 2019, so if you got your childhood vaccines before then, they might not show up.

Health Gateway also doesn’t show immunizations given by other health-care providers, such as family doctors, nurse practitioners or travel clinics, or immunizations received outside of B.C.

The ImmunizeBC website recommends contacting the health-care provider or community health nurse that would have given the vaccinations, even if they’re out of province or out of country.

If you can’t find an immunization record, Hu recommends speaking with a family doctor to determine next steps.

The doctor might recommend getting some vaccines again, which Hu said is safe to do, or getting a blood test to check your body’s immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases.

ImmunizeBC says blood tests “are not routinely recommended or available for all diseases.”

“The single most important thing is to ensure that everybody born after 1970 has two doses of the MMR vaccine,” Hu said. Adults born in Canada before 1970 are assumed to have had measles as a child and no further action is required.

The measles vaccine exposes a person to “live vaccine,” which is a weakened version of the virus that allows the body to successfully fight it off without risk of illness beyond a low fever, fatigue, body aches and tenderness at the site of the injection, Hu said.

Pregnant people cannot get the MMR vaccine, and immunocompromised people may not be able to receive it, which makes it all the more important for those who can be vaccinated to get it, therefore increasing herd immunity and decreasing the risk of community spread for those who cannot get vaccinated, Hu said.

Immunocompromised people should speak with their doctor about their eligibility, he added.

These “live vaccines are definitely still safe,” Hu said. “We’ve been using MMR vaccines for decades around the world,” with high success rates, he added.

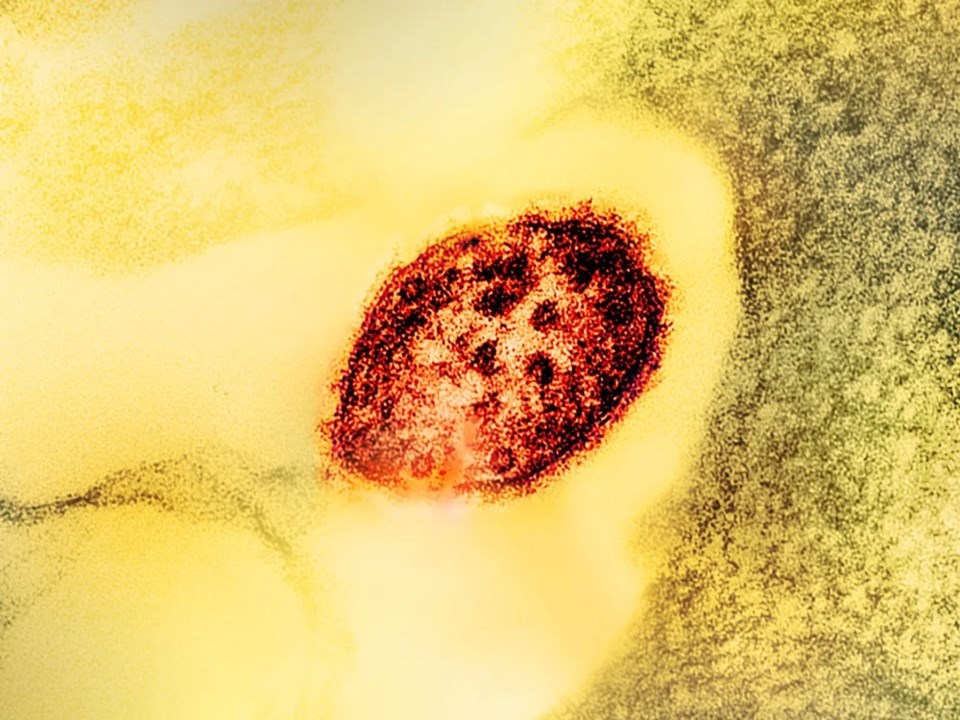

Photo: Image by NIAID via Flickr, Creative Commons licensed.