A handful of B.C. scientists say they have found a way to power chemical reactions that can transform atmospheric carbon dioxide into plastics, sugar, rocket fuel and even oxygen.

The breakthrough, developed at a laboratory at the University of British Columbia and published in the journal Device last week, offers a proof-of-concept that if scaled to an industrial level, could sustain future colonies on Mars.

All they need, said chemist and lead researcher Abhishek Soni, is a temperature difference of at least 50 degrees Celsius.

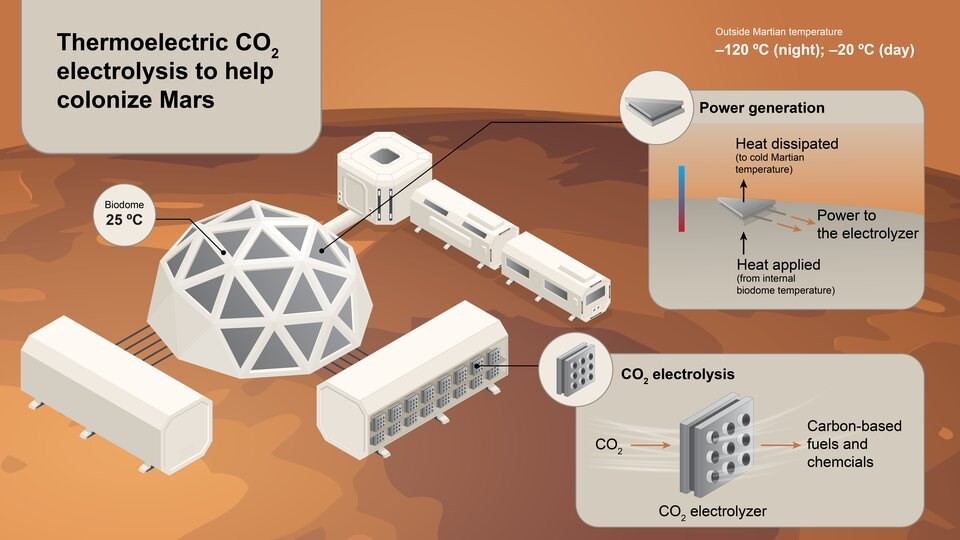

“Let’s suppose one day you’ll have a bio-dome for human habitation,” said Soni. “There’s room temperature and then minus 15 to minus 120 degrees Celsius outside on Mars. That is enough to power these CO2 electrolyzers.”

Doesn't need to be plugged in

Think of an electrolyzer (or reactor) as anything that uses electricity to convert one material into another. Feed enough electricity into the right kind of reactor and you can create hydrogen from water.

Curtis Berlinguette, a UBC chemist and senior author on the project, said their reactor converts CO2 into fuels and chemicals. That’s nothing new. What’s different about the UBC team’s reactor is that it never needs to be plugged in.

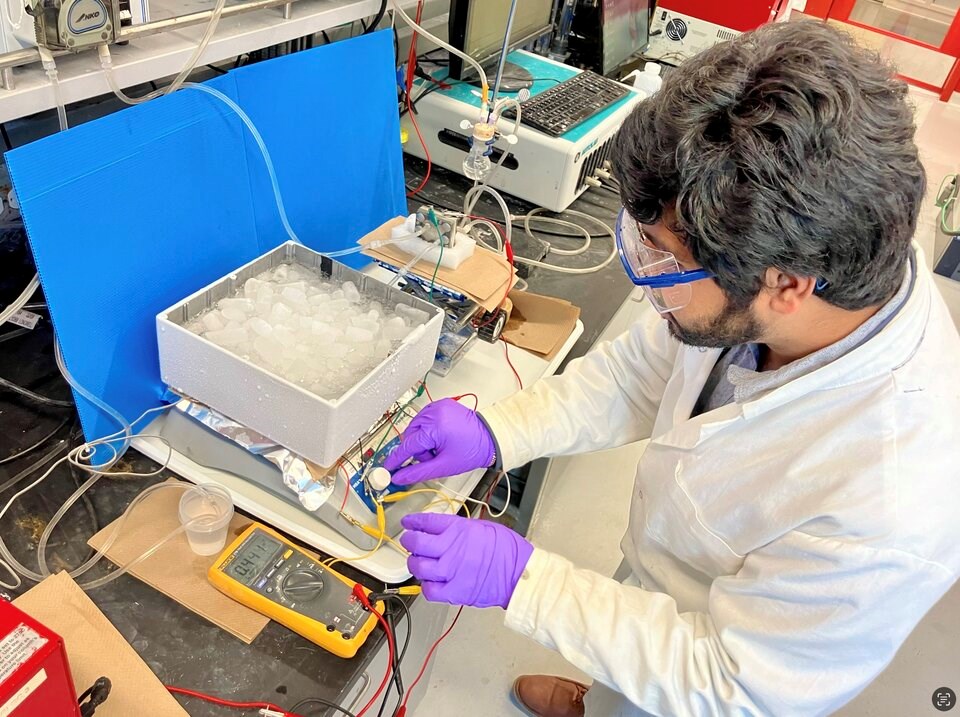

In a lab at UBC, the researchers used an ice bath and hot plates to simulate temperature differences found on Mars. When they hooked up their reactor to that temperature gradient — essentially a thermoelectric generator — they found it produced a charge powerful enough to drive reactions at a near industrial level.

For four hours, the team produced carbon monoxide from waste carbon dioxide in the same temperatures ranges a future colonist to Mars might face leaving their enclosed habitats. Fine-tuned and commercialized, the process has the potential to generate a vast quantity of resources, especially in a Martian atmosphere that’s made up of 95 per cent carbon dioxide.

There could be some applications of the technology on Earth, as well, said Berlinguette.

The researcher has already launched the start-up Sora Fuel out of Boston that aims to create carbon-neutral fuels. The company’s business model is to use electricity from wind turbines and solar panels to scrub carbon out of the air near airports and convert it into affordable, carbon-neutral jet fuel using only electricity, air and water.

Berlinguette says they are still fine-tuning the technology in a laboratory, and are seeking to commercialize the direct air capture method over the coming years.

Unlike the start-up, the UBC team’s latest finding swap the wind and solar infrastructure for extreme temperature gradients.

At the low end, Soni says even a two degree temperature change can produce a charge to power lights or heating — a fact that makes household geothermal pumps possible.

But manufacturing fuel and plastics using the group’s latest method would require more energy. On Earth, that would likely require setting up the reactors at thermal power plants or in other geothermal hot spots, where vents open to the planet’s surface in places like Mount Currie in B.C. or the entire country of Iceland.

Soni, who specializes in combining automation and robotics with clean energy research, said the thermoelectric generators are cheap, noiseless and could offer certain remote communities a powerful source of energy.

Powered by a near endless supply of geothermal energy, the generators could theoretically be run around the clock to directly capture carbon from the atmosphere and slow climate change. Critics, however, have cautioned that the scale of such a feat of geo-engineering would be immense and is not practical.

Berlinguette, for his part, sounded a note of caution about the technology’s application outside a cold, carbon-rich atmosphere on Mars.

“I’m not claiming you can build a unicorn energy company by building electrolyzers with these thermoelectric generators on Earth,” he said.

“It's just a different way of looking at the problem.”