When planning a visit to Whistler, one is offered a variety of accommodation options, from a tent at a campground to a hotel suite in Whistler Village. Another option is a pension, similar to a bed and breakfast but sometimes offering more than one meal. While municipal guidelines and requirements for pensions were introduced in 1983, by the summer of 1985 Whistler had only three official pensions, with another two in the approval process, and an unknown number operating illegally.

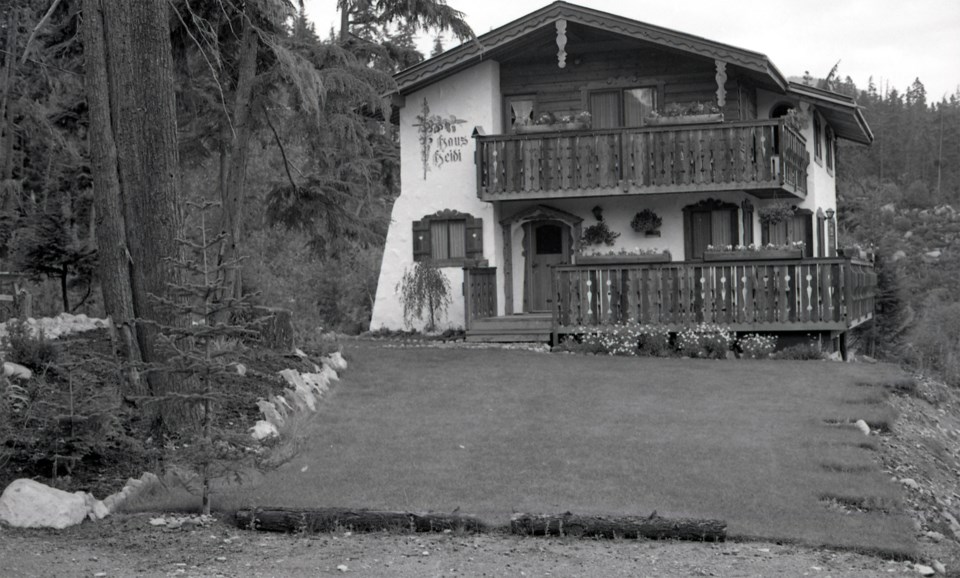

The oldest of the three, Haus Heidi on Nesters Road, was opened by Jim and Trudy Greutzke in 1978 and had a steady supply of return visitors to the four-bedroom pension by 1985. In White Gold, Luise and Erich Zinsli had Chalet Luise, a similarly sized pension to Haus Heidi. The largest of the three approved pensions was the eight-room Alpine Lodge Pension (not to be confused with Alpine Lodge in Garibaldi), run by Ruth Hidi with the help of her husband John and son Brian.

The typical cost of a double-occupancy room at any of the pensions ranged from $35 to $50/night in the summer months, and all three provided a substantial breakfast for guests, eaten together in a communal dining room whether guests knew each other or not. At Chalet Luise, breakfast might have consisted of a ham and cheese omelette, French toast, or bacon and eggs with homemade bread. Each pension also provided communal spaces for guests to relax and socialize.

Most pension proprietors had their own living quarters within the building, though Alpine Lodge was unusual in that its proprietors lived next door. Running a pension was a full-time operation, involving cooking, cleaning, changing linens, taking reservations, ordering supplies, and all other administrative duties, as well as ensuring guests felt at home, and often it was a family affair. At Alpine Lodge, Ruth Hidi took on the bulk of the pension work while her son attended school and John worked as a building inspector for the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District.

Two other pensions were also going through the approval process during the summer of 1985, making for a total of five “official” pensions. Nobel House in Alta Vista, owned by Jan Holmberg and Ted Nebbeling, was finishing up renovations and would then receive its business licence. In White Gold, Jacques and Ursula Morel were in the process of having their property rezoned from residential to tourist pension. The zoning bylaw at the time defined a pension as “a building used for temporary lodging by paying guests that contains guest rooms, common areas including a dining room intended for the use of such paying guests, and an auxiliary residential dwelling unit.”

There were both benefits and drawbacks to proper zoning. Authorized pensions were required to be members of the Whistler Resort Association (WRA), and so were eligible for its centralized booking services, had more encompassing insurance, and were usually better situated when applying for loans. There was also, however, a cost associated with authorization. Pension owners had to pay a $750 deposit to begin the rezoning process; pension-zoned properties paid higher sewage and water fees; pensions had to provide off-street parking; and properties had to make alterations to comply with commercial safety standards, all of which could add up.

Today there are still a number of pensions and bed and breakfasts operating in Whistler, though the definitions have changed some, and visitors continue to have many options when choosing a place to stay.