In a recent look through the Whistler Museum’s reference section, we came across another book aiming to teach skiing through a combination of the written word and photographs. Unlike Toni Sailer’s instructional flip book from 1964, Greg Athans’ Ski Free targets those who already know how to ski and are interested in learning about the sport of freestyle skiing.

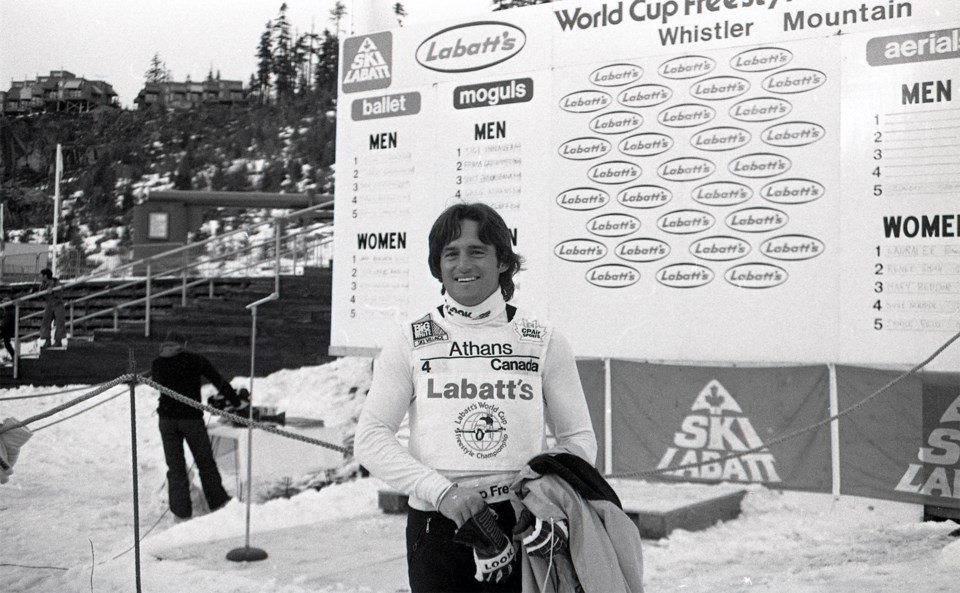

Greg Athans was a Canadian freestyle skier in the 1970s and ’80s, as well as a 15-time national water-skiing champion. Like many freestyle skiers, he had a background in downhill skiing and won a gold medal in the 1971 Canada Games in alpine slalom. In 1973, Athans became the first person to win gold medals in both the winter and summer Canada Games when he came first in water skiing. Among his freestyle skiing titles, Athans was the 1977 Labatt World Trophy Tour Champion, the 1978 World Ballet Champion and World Mogul Champion, and, as mentioned in a recent article about a very busy week on Whistler Mountain in 1980, Athans was crowned World Cup Freestyle Champion alongside Stephanie Sloan for the 1979-80 season.

Competitive freestyle skiing was still a relatively young sport when Ski Free was published in 1978. The first flip on skis was recorded in 1907, and moves found in ski ballet can be traced back to the 1920s. Flips and spins were seen in skiing exhibitions and shows throughout the 1950s and ’60s and, according to a brief history of freestyle skiing found in Ski Free, Doug Pfeiffer’s School of Exotic Skiing taught tricks such as the mambo, the Charleston and more from 1956 to 1962.

In the late 1960s, “trick skiing” demonstrations were caught on films such as Ski the Outer Limits and The Moebius Flip, but it wasn’t until 1971 the first professional competition took place in Waterville Valley, New Hampshire. Over the 1970s, competition circuits and freestyle camps became more popular, with freestyle skiing added to the Toni Sailer Summer Ski Camp on Whistler Mountain in 1973. Freestyle skiing was officially recognized by the International Ski Federation (FIS) in 1979, just one year after Ski Free was published.

According to Ski Free, freestyle skiing “offers the skier the freedom to do whatever he or she chooses and, possibly, to do what has never been done on skis before.” It begins, like Toni Sailer’s book, by instructing the skier on what type of equipment will be needed. Helpful notes and safety tips are also included, such as warning skiers not to have safety straps on their bindings for aerials as “a loose windmilling ski can be dangerous,” and suggesting that when learning somersaults and flips a helmet might be a good idea.

As helmets were not a standard piece of ski equipment at the time, a “well-fitting hockey helmet” was considered sufficient. Other equipment suggestions also place Ski Free in a certain time, as a “light mini-cassette recorder” and a fanny pack are described as useful for choreographing ballet routines.

Ski Free devotes a chapter to each of the three disciplines of freestyle skiing in 1978: moguls, aerials and ski ballet. With descriptions of techniques, common problem areas and solutions, and of specific tricks accompanied by photographs by Allan de la Plante, it would have been a great guide for those looking to learn more about the sport without today’s easy access to videos and film clips. Without the ease of looking up options on the internet, the book also provided a list of summer ski camps and off-season training programs for those looking for in-person instruction.

Freestyle skiing has changed a lot since Ski Free came out in 1978, and not all of the information is still relevant. Some of the tricks described are no longer so common (especially as ski ballet is no longer an official discipline), but for anyone wondering what is involved in a Legbreaker Pivot, a Shea-guy, a Daiglebanger, or an Athans’ Walkover, the step-by-step instructions may prove very useful.