A decision on Whistler’s 2025 budget and a proposed 9.1-per-cent tax hike was deferred this week, as elected officials wrestle with how to pay for several looming costs facing the municipality without creating undue sticker shock for the public.

At the regular meeting of council on Tuesday, Dec. 3, mayor and council heard a presentation from Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) staff on next year’s budget guidelines. Ultimately, staff landed on a proposed a 9.1-per-cent increase to property taxes; an eight-per-cent increase to sewer parcel taxes and user fees; a five-per-cent increase to solid waste parcel taxes and user fees; and a four-per-cent increase to water parcel taxes and fees.

Following the presentation, officials debated the prospect of implementing a property tax hike nearly a full point higher than last year’s 8.18-per-cent increase, which itself followed an 8.4-per-cent hike the year prior, at a time when many Whistlerites are having to tighten the purse strings.

“I don’t want to see an increase [of] more than what we had last year,” said Councillor Jessie Morden. “This is a huge hit to homeowners who are seeing increases across the board with everything—homeowners and businessowners.”

Morden introduced an amendment asking staff to come back at the next council meeting with insights into how an 8.1-per-cent tax rate would impact next year’s budget, as well as the five-year financial plan stretching to 2029.

The RMOW, like municipalities across the province, is contending with its own rising costs. As Whistler’s population has grown and its demand for services along with it, there hasn’t been a corresponding growth in new properties to add to its tax base. Construction costs have skyrocketed. The resort’s aging infrastructure is in need of upgrade.

Then there are the so-called “big rocks” in the RMOW’s path—three significant costs the municipality will have to deal with in the coming years. The first and most costly surrounds policing: once Whistler’s population hits 15,000, an inevitability in the 2026 census, the municipality’s share of the roughly $5.4 million in annual policing costs will rise from 70 to 90 per cent. The second major looming cost is for firefighting, a large chunk of which will go towards staffing the No. 3 Fire Hall in Spring Creek full-time, a decision council greenlit in January. The third big rock is for transit, with staff anticipating the Canada-B.C. COVID Safe Restart grant reserve to dry up by early 2027, foisting another roughly $1 million back onto the RMOW.

Compounding these financial pressures are declining non-tax revenues—namely from parking and the Municipal and Regional District Tax, which is based on hotel stays—as Whistler continues to see lagging tourism numbers. It’s also partly why RMOW staff have “focused internally on saving, shifting or redeploying, not expanding and, wherever possible, we kept non-payroll operating costs level with 2024,” explained CAO Ginny Cullen.

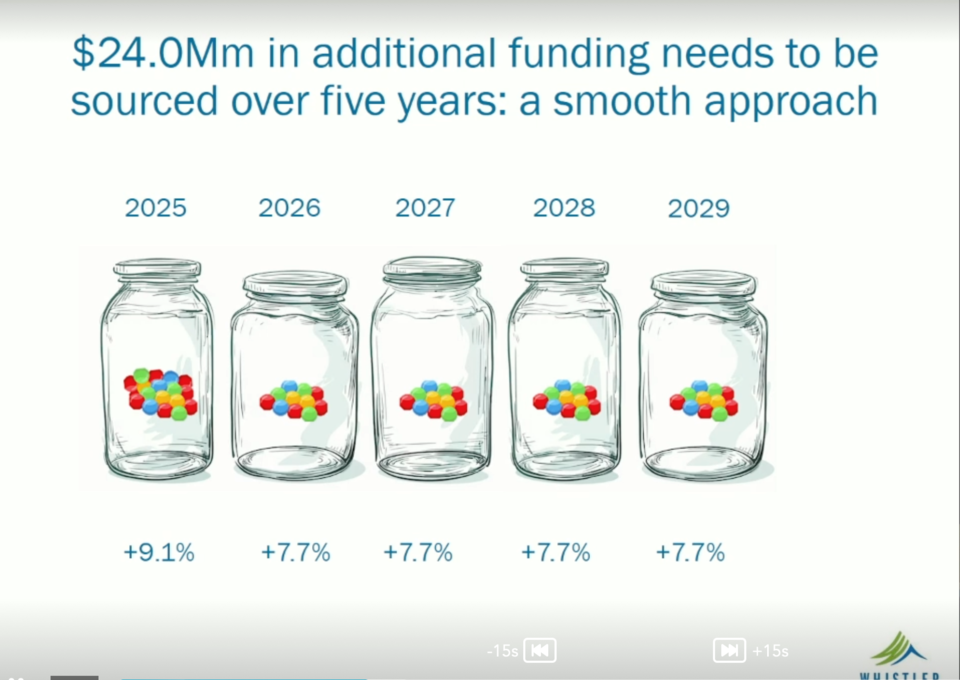

Given these economic realities, staff recommended taking a “smoothing approach" to its five-year budgetary outlook, with a view towards keeping property tax hikes relatively consistent over the next half decade, while also increasing contributions to reserves. In order to generate the $24 million in additional funds the municipality requires between 2025-29, staff proposed tax increases of 7.7 per cent each year from 2026 to '29, along with the 9.1 per cent floated for 2025. The rates floated for 2026 and beyond are not written in stone and are likely to be higher than 7.7 per cent when all is said and done, given they don’t account for any new additional municipal services.

“To imagine that no new services will be introduced over this period feels a bit unlikely, and so we’ve created space within this approach for those new services to come in and still achieve smooth increases across the planning horizon,” said municipal CFO Carlee Price. “Large increases in Year 1 allows room for additional increases in subsequent years.”

The other avenue staff laid out, but ultimately did not recommend, was a “pay-as-you-go” approach that would see tax rates fluctuate widely year over year, with proposed increases of 5.8 per cent in 2025 and 7.6 per cent in 2026, before spiking to 13 per cent in 2027, followed by 7.4 per cent in 2028, and 6.3 per cent in 2029.

“Part of the challenge here is we’re looking at economic realities that are real, so we are going to have to deal with them at some point, and whether we deal with them now or later, I think we will all have a tough time going to the community in 2027, saying, ‘We got a [smaller] increase in 2025, but we have a 16-per-cent tax increase for you in 2027,’” said Mayor Jack Crompton of the pay-as-you-go model. “That could very well be a reality we end up with if we can’t do this now.”

Particularly given the state of the RMOW’s dwindling reserves, more than one official expressed support for the “smoothed” budget, even with its potential 9.1-per-cent tax hike in 2025.

“The five years that we’re phasing here, even at 7.7 per cent [proposed for 2026 to ’29] is not really addressing a shortcoming,” said Coun. Jeff Murl, referring to the need to increase reserve contributions. “I don’t think 9.1 is comfortable, but I also know that the variables coming our way, and the unknowns, will certainly make that higher. So, trying to be accurate in this first year is important, but looking across the whole spectrum [of the five-year financial plan] is important, too.”

In many ways, the frank debate around the council table Tuesday night hit at the balance many government leaders past and present have tried to strike between making decisions for the best of their community without alienating an electorate reluctant to take on any form of tax increase. In Whistler, one of the priciest communities in the country where the public enjoyed a three-year tax freeze between 2012 and 2014, sensitivity to any rate hike is especially high.

“I’ve been a part of councils that had big increases in subsequent years and said, ‘Hey, we’re doing this for the right thing. We need to do this.’ Our reserve balances were not what they should have been—and it was wildly unpopular,” said Coun. Ralph Forsyth, who sat on the only council in Whistler’s history to be completely swept from office, in 2011. “Let’s understand the political realities of this. If you don’t care about winning another election—personally, I don’t, really, so I’ll defend the 9.1 if you want to go for that, but no one’s going to care when I’m out the door.”

Coun. Jen Ford, who voiced support for staff’s recommended 9.1-per-cent tax hike, acknowledged the difficult decision before them, lobbying for the municipality to consider what further costs can be dropped in the coming years.

“None of this is easy, because we are at a point in our very young life as a community where big things break, and no matter how much saving this community has done in reserves, it didn’t anticipate the costs going up,” said Ford, citing how building costs, for instance, have increased by at least 50 per cent since 2018. “I would challenge us for the next two years to look at, what can we do without? Because people are now making those decisions in their home.”

Whistler council’s next meeting is Tuesday, Dec. 17, the last meeting of the year.