Roger McCarthy learned fairly quickly that Russians have their own ways of doing business. Tapped with developing Rosa Khutor, a fledgling ski area in the Caucasus Mountains that was to become the alpine skiing venue for the 2014 Sochi Olympics, McCarthy’s laidback demeanour and hands-on work ethic threw his Russian minders for a loop.

“They’re not used to the boss going out in the field and getting his shoes dirty,” McCarthy told Pique in a 2007 interview. “But I firmly believe you can’t manage this business from the office.”

It’s a philosophy McCarthy carried with him from his early days in Whistler on ski patrol to the pinnacle of a glittering career as one of the snowsport industry’s most influential executives. He knew if a job was to be done, and done well, it wasn’t going to happen from the back of the pack.

“He understood how an organization should run and that it should be led from the front,” said friend Duane Jackson.

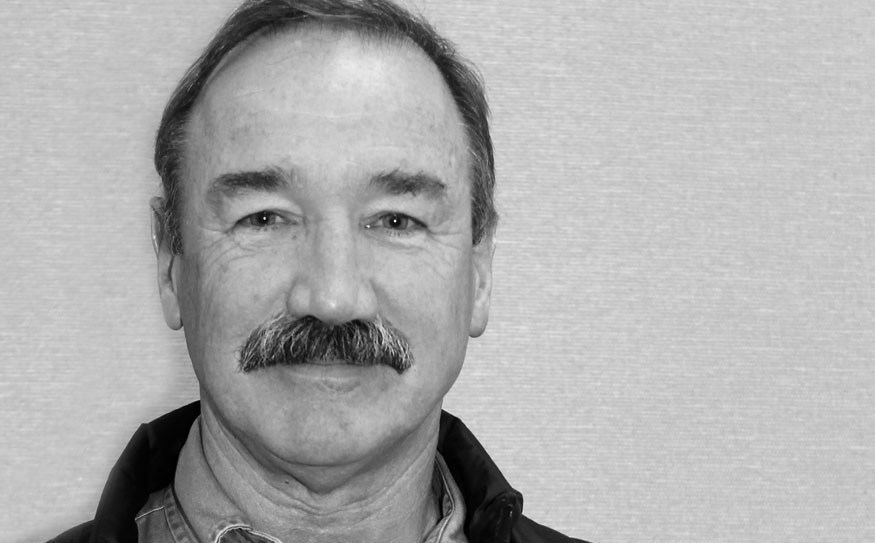

The longtime Whistlerite, former councillor and Canadian Ski Hall of Famer died Saturday, Jan. 4 from a suspected heart attack. He was 74.

The seeds of McCarthy’s remarkable career, spanning half a century and multiple continents, were planted as a youngster in his native New Zealand, where he grew up skiing Mount Ruapehu on his father’s handmade wooden skis. It was there one day he saw Super 8 footage of Whistler Mountain, then a plucky, upstart ski area, inspiring him to make the move across the globe.

“He came here, like so many people, with a backpack and an intention to stay for a year, and he ended up giving his whole life to this place and helping create what we’ve all fallen in love with,” explained Mayor Jack Crompton.

Arriving in Whistler in 1972, McCarthy initially worked as a handyman at the Cheakamus Inn before landing a job as a lift operator. It was there he met members of the ski patrol, motivating a career change, excited by the prospect of carrying explosives around on his avalanche control missions. Recognized for his affability and caring nature, McCarthy quickly moved up the ranks at Whistler Mountain, first as assistant patrol leader, then safety supervisor, then as safety and lift ops supervisor.

Beloved by his employees, McCarthy was a natural leader who worked hard to cultivate a fun atmosphere for his staff, whether he was sharing one of his legendary stories, playing a prank or racing his patrol team down the mountain.

“It was so much fun working with him. He could always lighten the air. He was not a guy you saw get angry or anything like that,” said Councillor Cathy Jewett, who first met McCarthy when she was on patrol, one of the first women on the team. “He was a real big cheerleader for me. It wasn’t always easy working on the patrol with all those guys. He always pumped me up and got me going again. He made me believe I could do whatever I wanted.”

In 1991, McCarthy was tasked with one of the biggest missions of his career: turning around Mont Tremblant in Quebec, then on the brink of collapse and widely considered the worst ski resort on the continent. Within five years, it was named the top ski area in eastern North America, thanks in no small part to McCarthy’s steady hand.

“Roger played a huge role in the Canadian ski industry,” said friend John Hetherington, who met McCarthy as a lifty in the early ’70s. “He was always a happy, friendly guy who would talk to anybody. He was very competent.”

McCarthy’s leadership didn’t go unnoticed: in 1998, he was promoted to a senior VP role for Intrawest’s eastern region, relocating to New Jersey, where he became known for his ability to attract new people to snowsports through a suite of learn-to-ski programs, beginner terrain, and innovative rental shops.

Two years later, he was headhunted by Vail Resorts to become Breckenridge Ski Resort’s new COO, before Keystone was added to his portfolio in 2002, putting him in charge of two of the most popular ski areas in the U.S., both of which saw major growth under his leadership.

In 2007, he moved to Russia to oversee the layout and initial construction of three gondolas at Rosa Khutor, readying the nascent ski area for its Olympic debut in a relatively short timeframe.

Through all his time away, McCarthy never forgot his home away from home, itching to return to his Whistler residence on the shores of Alta Lake. In 2011, McCarthy was elected to council, and his West Side Road home regularly served as “a community think tank” for elected officials, with discussions—and adult beverages—flowing well into the night. At municipal hall, McCarthy served as council’s “glue guy,” lending his unique perspective to the business of local government, Crompton said.

“He helped you listen to the other people around the table,” the mayor added. “He was able to see a side of things others weren’t able to. He was also able to draw out people’s insights that they weren’t able to express themselves.”

Even after reaching the highest heights of the ski industry, McCarthy never lost that child-like awe he first felt watching that grainy footage of Whistler Mountain so many years ago. Joy, more than anything else, was his animating force, and he remained grateful for the chance to pursue his passion, in the place he loved more than anywhere else, until his final days.

“I mean c’mon, it’s a phenomenal thing that we’re doing,” he once told Pique. “Let’s make sure we keep reminding each other just how special this business really is.”