Ask Dr. Will Ho about his experience practicing family medicine in Pemberton, and he might tell you a story about a bike ride he took a couple of years ago.

“It was the end of a work day, I was tired. I was kind of feeling deflated out on the trail, not riding particularly fast, just wanting to get it done, get the exercise, go home,” he recalled. “Then in amongst the trails, there was a patient I’d been looking after who I knew was undergoing treatments for cancer.

“You can only imagine the kind of toll that has on your body, and here this patient was, pedalling up the same trail I was on, having a great time,” Ho said. “It just gave me a whole new perspective in that instant moment.”

It’s one of many examples where, “what I’ve gotten out of looking after my patients, I don’t think they realize,” said Ho. “As much as they get out of my care, I also get a lot back from being in that privileged position and looking after them.”

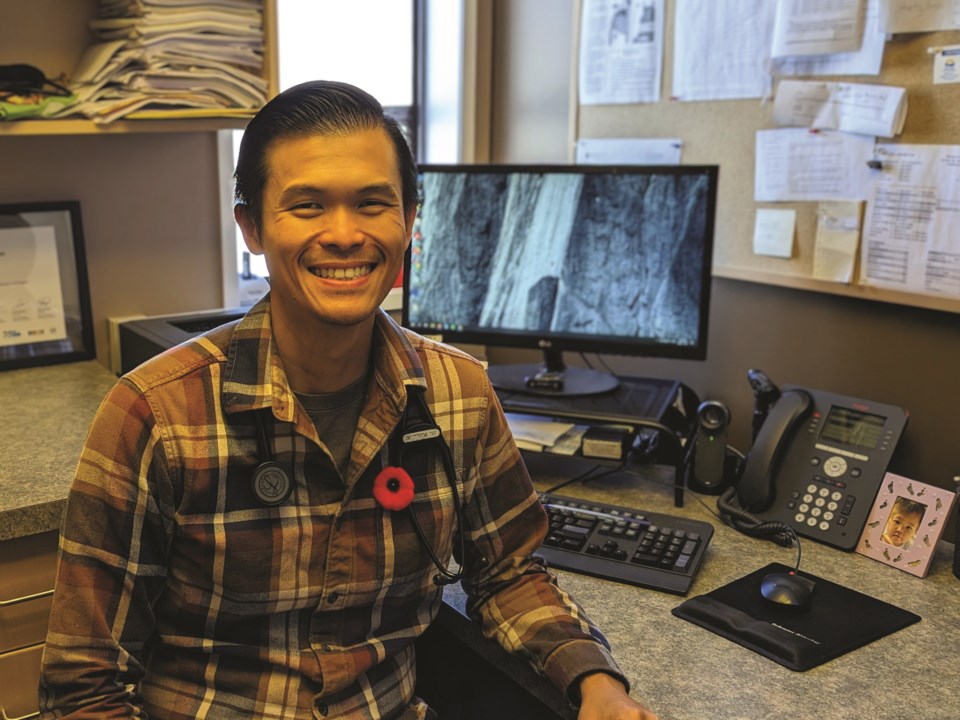

It’s moments—patients—like that Ho will miss after he hangs up his stethoscope on Nov. 17.

After six years practicing in Pemberton, Ho, his wife, and their two young children are packing up their life in the valley and heading home to Cairns, Australia to be closer to family.

Since moving to the resort, Ho has provided residents of the valley and nearby First Nations, from Lil’wat to N’Quatqua, with both primary and emergency care as a family physician with the Pemberton Medical Clinic. He also served as physician lead for B.C.’s Rural and Remote Divisions of Family Practice.

Ho said he had an idea of what rural medicine entailed, after previously practicing in rural Australia and as a commissioned medical officer in the Royal Australian Navy for the better part of 10 years, but that doesn’t mean there weren’t a few professional challenges.

Pronunciation, for one, said Ho, recalling one instance where it took him a few minutes and more than a few attempts to catch the attention of a waiting patient named Craig, not to mention struggles with the province’s electronic medical record system dictation software picking up his Australian accent.

Another challenge, though not necessarily unique to Pemberton, was the inevitability of working in a resource-limited environment, he explained.

“We hold ourselves to a very high standard, and the work we put out is something that we can be proud of,” he said. “But sometimes it’s difficult when, a lot of times, we’re working with [limitations].”

When dealing with serious incidents like resuscitations or trauma, in particular, “by the time we speak to the specialist down in the city, which we invariably have to do in order to arrange transfers, they’re asking us, ‘What does the CT scan show?’ or ‘What did this X-ray show?’ or ‘What did these blood results show?’” he explained. On a weekend or overnight, “we literally don’t have any of those, with the exception of X-ray sometimes.”

Ho continued, “To relay that back to them, they’re like, ‘How have you managed to do all of this without those tests?’ But we just use our clinical skills—you look, listen ... and just make do.”

To that end, Ho said he feels comfortable walking away from the Pemberton clinic knowing he’s leaving his patients in the capable hands of “by far the best bunch of colleagues,” he’s worked with, including reception staff, nurses, nurse practitioners and the five usual physicians who staff the valley’s emergency room.

Though B.C.—and Canada as a whole—is experiencing a well-documented ongoing family doctor shortage, Ho said the clinic is currently well-positioned to serve the valley’s rapidly growing population.

In terms of staff shortages, “In Pemberton, disruption has been reasonably limited,” he said, citing a roster of dedicated nurses, some of whom live locally and others who commute to Pemberton, and the help of locums—or substitute medical professionals—who travel to help out when needed.

Paramedic shortages in the BC Ambulance Service have been more difficult, Ho said, as “that really limits our ability to get people to the places they need to be in a prompt manner.”

Though the clinic hasn’t yet been successful in finding a replacement for Ho, his patients will be reallocated to the practice’s other doctors and nurse practitioner. In addition, a new family doctor who has committed to working out of the Pemberton clinic a couple of days a week will help fill the gap in the meantime.

In speaking with Ho, it’s clear his personal experience with family medicine has, despite the presence of challenges, been nothing short of overwhelmingly positive. But with data showing fewer Canadian medical students are choosing to pursue family medicine compared to other specialties—according to the Canadian Resident Matching Service, a not-for-profit connecting med students with residency placements, 30.7 per cent of Canadian medical students ranked family medicine as their first choice in 2022, down from 38 per cent in 2015—how can the powers that be help those students see the benefits of a career in primary care?

“One of the really obvious things is to pay them better and recognize the value of family doctors,” said Ho. “The announcement on Monday (Oct. 31) by Health Minister Adrian Dix and the ministry with this new remuneration model, for family doctors, I think is a fantastic step in the right direction.”

B.C.’s new payment model will give family doctors like Ho’s colleagues a substantial raise: starting in February 2023, the Ministry of Health says a full-time family doctor in B.C. will reportedly earn $385,000 annually, on average, up from the 2020-21 average of $250,000.

The new compensation model, the result of negotiations between the province and physician advocacy groups Doctors of BC and BC Family Doctors, represents a retreat from the current fee-for-service model, the province explained in a release, under which doctors are paid about $30 for each patient they see per day regardless of the nature of those patients’ health concerns.

Under the new model, physicians’ earnings will depend on factors like time spent with a patient, the number of patients seen in a day, the number of patients supported through that doctor’s office, and the complexity of a patient’s health concerns, as well as administrative and overhead costs family doctors are currently responsible for covering.

Officials believe the plan will make a difference in improving health-care across the province, said Dr. Ramneek Dosanjh, president of Doctors of BC, in a release.

“Over the last months, the provincial government has listened to the voices of physicians who passionately care about our patients,” he added. “The new payment model option for family doctors is unique in Canada, bringing together the best of a range of payment methods. The goal is to not only stabilize longitudinal family practice, but to also make it sustainable and rewarding. Everyone deserves a family doctor, and this new option is a major step toward making that goal a reality.”