A local doctor has launched a mobile house-call service in Whistler that he sees filling a growing gap in the resort’s healthcare landscape.

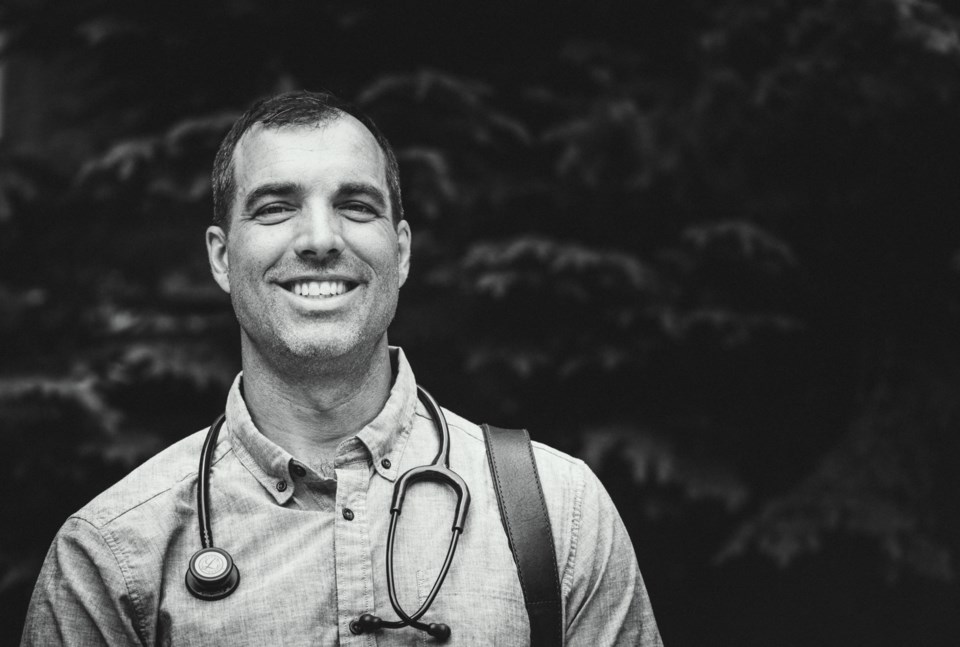

Dr. Clark Lewis, an emergency doctor currently on sabbatical from the Whistler Health Care Centre, launched BettrCare earlier this year after he saw a dire need for greater access to healthcare in a community where clinics are already overloaded and the high cost of living and real estate has made it difficult to recruit new physicians.

“We have a shortage of doctors in Whistler, obviously. That’s no secret,” Lewis said. “The ones who are left are doing a really good job but they are overworked. They are working as hard as they can and they are servicing far too many patients. It’s not sustainable.”

The BettrCare team uses a combination of house calls, virtual consults, and a mobile van for intimate exams, with the goal being to eliminate long wait times for appointments. Lewis said the model is set up to see patients the same day they request care, with BettrCare currently servicing an average of about 10 patients daily.

“For patients, they get easy access to primary care, easy online booking. You don’t have to call and play phone tag with reception. You don’t have to wait to get seen. You don’t have to park and wait in the waiting room,” Lewis said. “You’re just doing your thing at home and it kind of follows that work-from-home, stay-at-home culture since COVID, where you’re doing your thing at home and your groceries show up and your Amazon package shows up and now your doctor shows up.”

Lewis said the concept came in response to what he views as an outdated clinic model that forces family doctors to cram in as many patients as possible just to make ends meet.

“Overhead is the big problem for family doctors in B.C. now because it’s very expensive to buy or lease a space. So they end up having to pay a big chunk of their billings to overhead, and the result of that is they have to see a million patients a day to try to make a living,” explained Lewis.

Dr. Rita McCracken, family physician and assistant professor in UBC’s faculty of medicine, agreed the current fee-for-service model, which asks doctors to cover a host of overhead costs, from IT to personnel, is putting undue strain on family practices.

“Imagine if a public school was funded based on how much money the teachers could get from the students. When you put it in that context, [the fee-for-service] model is immediately fallible,” she said. “Even if you can make kids worth certain amounts and get that money from the government, you’re putting this pressure on the teachers that is taking them away from teaching. That is the same thing that is happening with family medicine.”

While house-call services—a fixture of rural healthcare for generations—are certainly not unheard of in B.C., they are primarily used for geriatric and immobile patients. The guidelines state that a physician can bill a house call “only when the patient cannot practically attend a physician’s office due to a significant medical or physical disability or debility.” For now, Lewis has been permitted to bill house calls during regular hours as he would a clinic visit, arguing that the doctor shortage has necessitated such a service.

“[Patients] have to not be able to be seen in any other way, so how about this scenario where there aren’t enough doctors and they have to wait weeks to get seen? Would that be necessary?” Lewis said. “So far I’ve been getting paid through billing that code but I know that’s going to get challenged at some point by those who are unhappy about it.”

That speaks to another potential barrier for BettrCare: the backlash from family physicians. Lewis acknowledged the service is disruptive to the traditional clinic model, but he doesn’t see any other way to improve access to care locally.

“I’m doing this with the lens really focused on what’s best for patients. I have a sincere desire to minimize the carnage for my colleagues along the way, and that I haven’t figured out yet,” he said. “If someone has a better idea, then I’m all ears. I can’t think of any other way to get around these issues and I don’t think the real estate rules are going to change in Canada ever, which really sucks. This ties into a much bigger existential issue for Whistler in general. Are we going to turn into Aspen in 10 years? Because that’s awful and that’s where we’re headed. It’s a big problem.”

For her part, McCracken believes a community-based healthcare delivery model is the way forward, a concept that has started to pop up at community health centres across B.C.

“We need to make primary care delivered more like public schools, so have community-funded care where there would be a clinic for a community and that community would determine their needs and they would hire the people,” she explained. “Most primary care systems around the world use some kind of model like that where you are connecting funding to the community and then hiring doctors, versus in Canada, where the vast majority of primary care is funded via doctors’ fees.”

However, McCracken said transforming such a deeply entrenched model could prove incredibly challenging.

“The big problem, I think, is that physicians have a really important role to play in society and they’ve also been given a very important voice at the negotiation table, and you can imagine that if those voices have a funding mechanism that allows them to fund themselves in a very open way than having a systemic change is going to be a problem,” she said.

“I’m really, really worried. The needle hasn’t moved in at least 20 years and it’s probably gotten worse in the last few years. I think that if we really want to make a change, what we need is not just doctors and policy makers at the table, we need communities at the table as well.”

Learn more at bettrcare.com.