Glacier monitoring has a long history in the Whistler area. Karl Ricker has been monitoring Wedgemount Glacier for more than 45 years, a project instigated by Bill Tupper that also included Don Lyon on the original crew. The team’s first sighting of Wedgemount Glacier was from Wedge Mountain in 1965, when the glacier was floating on Wedgemount Lake.

Why monitor glaciers? Glaciers grow and shrink in response to changing climate, so their movements mark changes. Monitoring data allows researchers to assess ecological and hydrological effects on species (including humans) living in the area or downstream. Researchers can also use the data to predict future changes and effects—like how shrinking glaciers will affect water availability.

Monitoring on September 12, 2021, revealed that Wedgemount Glacier receded a whopping 81 metres within the last year. This is by far the greatest annual change on record going back to 1900. For comparison, last year’s recession was way above average at 30 metres. So, what happened? There are probably a few contributing factors.

One is the topography of the mountain. Monitoring last year showed the glacier on the far edge of Tupper Lake with a steep slope behind. This year a huge chunk of ice had broken off at the point of a rock outcrop. While it was common to see small broken off pieces of ice floating in Tupper Lake in the past, this is the first time during monitoring that the glacier has broken off on land. The broken off piece of ice will melt faster now with rock on all sides heating it up.

Another factor is the heat dome that we suffered through between June 25 and July 1 that was called the deadliest weather event in Canadian history. It seems it was deadly not only to people—Wedgemount Glacier lost several years of its life in just one summer. With a Whistler Valley temperature maximum of 42.9 degrees on June 29, this dome heated the glacier so much that it just couldn’t hang on any longer.

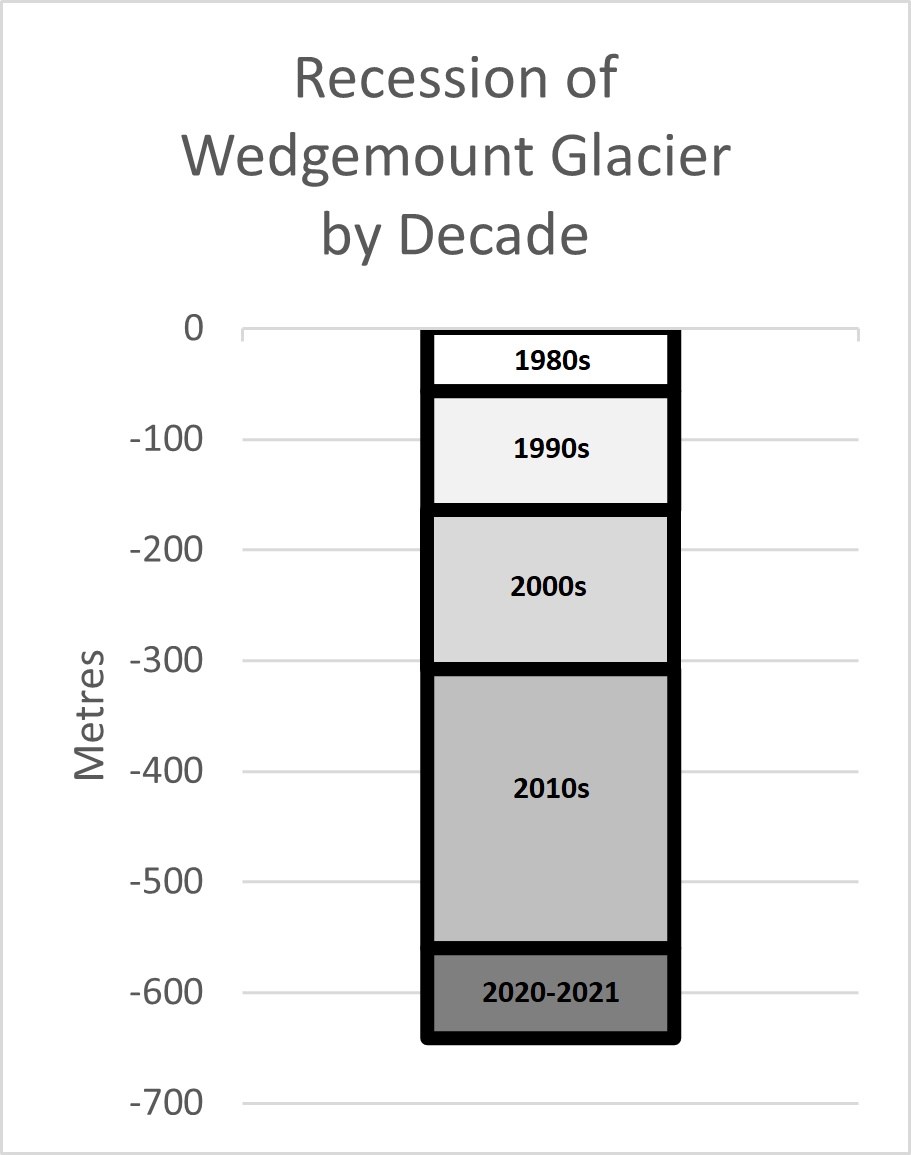

Looking back at 40 years of research, recession during each decade varies considerably and has been steadily growing. In the 1980s, total recession was 56 metres; in the 1990s it was 108 m; in the 2000s it was 143 m and in the 2010s total recession was 252 m. The increased rate of recession has significant implications for local hydrology and species that depend on glacier meltwater.

After more than 45 years of surveying, Karl is near retiring and will be handing off this monitoring project to a younger generation of researchers. The contribution Karl has made to our understanding of the natural world is unmatched. He has explored the mountains, valleys and regions around Whistler perhaps more than any other person alive. A remarkable naturalist, Karl has not only contributed glacier-monitoring data but has also studied the flora and fauna of our region. He has contributed in huge ways to our knowledge of the animals and plants that inhabit and surround our community. He has also been a tireless advocate for responsible development and sustainable practices that protect these spaces.

Thank you, Karl!

Naturespeak is prepared by the Whistler Naturalists. To learn more about Whistler’s natural world, go to whistlernaturalists.ca.