For Johnny Jones, the work of preserving the Lil’wat Nation’s cultural and historical sites was less a job than it was a calling.

“It’s just a way of life to me. It’s the way I was brought up,” said Jones, who worked for more than 30 years as a cultural technician in the Lil’wat’s Lands and Resources Department before his retirement in 2021.

But it was long before then that Jones was set on the path that would come to define his life’s work.

“It all started when I was a young boy, back in ’69, when I first saw our house being dismantled by non-natives and being taken away. That’s when I realized that the culture has to be saved. Everyone was being taken away back then,” he remembered.

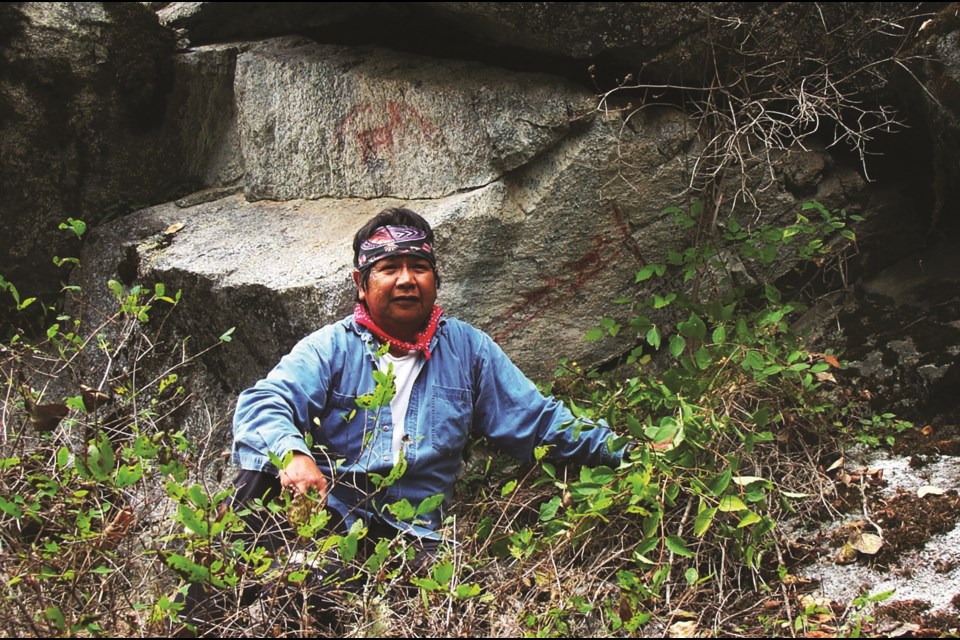

But not Jones. From an early age, Jones impressed his family with his curiosity and innate ability to unearth long-forgotten cultural sites, like the rock painting he discovered at the tender age of seven on a hill near where the Pemberton Industrial Park now sits. He would marvel at the paintings, drawing what he saw to show his father and peppering him with questions about what they meant.

“I was questioning my dad, why all the paintings are out there, and he was telling me some people training to become medicine men would leave their mark on the land, using paint with red ochre or a fungus from the fir trees there,” Jones said.

Soon enough, a decision was made: recognizing Jones’ gift, his family would prevent him from being sent to residential school so he could continue his cultural training from home.

“My grandpa was a medicine man … and he knew that I had something to pass on, so he told my parents not to send me to residential and that they wanted to teach more cultural stuff to me,” recalled Jones.

Throughout his career, Jones and the Lil’wat Land and Resources Department have helped preserve more than 200 archaeological sites on the Nation’s territory, and repatriated dozens of cultural items from museum collections, like the stone pieces and baskets returned to the Nation from the Pemberton Museum and a 565-year-old twin fish bowl repatriated from a Vancouver museum.

“When I’ve been travelling around the country to different tribes, I notice a lot of artifacts that come from here. I say something about it and people return them,” Jones said. “That’s how a lot of artifacts are being returned.”

If it was Jones’ job to locate and protect the Lil’wat’s cultural sites and items, it was Lex Joseph’s role to interpret and contextualize their significance. A Lil’wat elder who also worked as a cultural technician with the Lands and Resources Department until his retirement, Joseph called himself the Lil’wat’s “in-house advisor” on stories and legends.

“We spend a lot of days in the field, and those are the exciting parts, like when we find a rock painting or a culturally modified tree,” he added.

Today, there are only three known cave paintings remaining on Lil’wat land, after several sacred pictographs depicting legends and marking ancient burial sites were destroyed more than 30 years ago to make way for new logging roads, an act that precipitated the 1990 roadblock at Ure Creek and led to the arrests of dozens of Lil’wat protesters. In discussing their meaning, Joseph said, “A lot of the rock paintings were made by children [depicting] their pre-pubescent dreams.”

One of the Nation’s most important archaeological discoveries came in 2016, when researchers carbon-dated a site next to the Birkenhead River that showed it had been occupied by the Lil’wat between 300 and 1,100 years ago, and was used as a seasonal camp as far back as 5,500 years ago.

Although he’s technically retired, Jones said he will be back at another archeological dig planned for this summer, and he’ll have the next generation of Lil’wat cultural technicians in tow.

“Now I’ll be starting to attend meetings again and doing another archeology dig and trying to keep passing on the cultural knowledge to the people and the younger generations. Even the older people need to re-learn,” said Jones, adding that he has trained “at least” two dozen young Lil’wat over the years to carry on this vital work.

“A lot of our tribal members who are older than me don’t even know our culture, and I was so lucky to be brought up in our cultural ways. They’ve been sent to residential and been brainwashed by the schools.”

Joseph welcomed the next generation of cultural experts, adding that he’s happy to continue offering guidance wherever he can.

“I am excited about their involvement and wish them good luck,” he said. “When we started, we didn’t have any guidance from anyone, but the new ones coming after us have plenty of background resources in our office and in our mapping.

“It’s very important to provide future generations a cultural link to their past.”