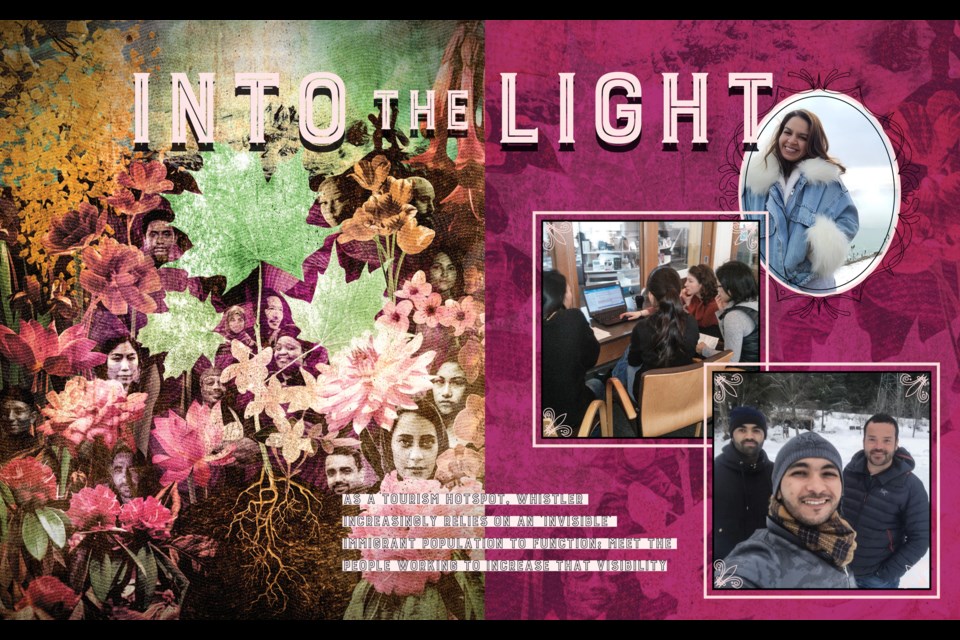

In a town like Whistler, it can be difficult to differentiate the local from the tourist or the hotel clerk from the skilled snowboarder. These permeable boundaries are easily blurred by the ebbs and flows of a seasonal workforce, and not much feels static. But this leaves the picture incomplete; some colours are missing in the depiction of this community.

Amidst the influx and outflow of people and snow, some very pertinent gaps in the fabric of resort towns’ social structures remain: unaffordable housing, workers from diverse backgrounds veiled in the ‘backcountry’ of hotels and restaurants. It is difficult to maintain heterogeneous cultural practices in homogenized spaces, and societal acceptance of diversity takes different forms, the ambiguity of which can sometimes be more destructive than transformative.

It seems obvious that towns like Whistler need immigrant workers to support the economy as much as immigrant workers need these towns. There is a blanket of tolerance, but now more than ever it feels like the scales are tipping. Tipping those scales upwards will certainly require effort—welcoming newcomers and sensitizing ourselves to the diverse array of backgrounds and realities that now live in town. Things can go bad just as easily; simply acknowledging that we are different does not hold any ambition for a common project or goal. As Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel said, “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference.”

[Editor’s Note: For the purposes of this article, when speaking of immigrants, Pique is referring broadly to first-generation, non-Canadian citizens who have moved here primarily for reasons other than short-term recreation. Pique intentionally interviewed immigrants from cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds that are both geographically and traditions-wise more distant from Canada and its customs.

Pique would also like to acknowledge that the vast majority of people who call the Sea to Sky home are immigrants and settlers on the traditional, ancestral, unceded territories of the Lil’wat and Squamish Nations who have lived on these lands since time immemorial. As such, this story does not intend to promote an incomplete history of unwanted settling on Indigenous lands, but rather explore one type of relationality between immigrants and locals by shedding light on some of the lived realities of individuals crossing borders and cultures.]

Gaps in the net

Since 2018, Joel Chevalier, founder and owner of Whistler-based Culinary Recruitment International (CRI), has helped recruit more than 200 chefs to the Sea to Sky in an effort to fill the shortage of skilled and critical workers. “The busier communities like Whistler get, the more adaptive employers will need to be towards a diverse group of employees,” he believes.

Recruiting skilled workers primarily through Canada’s Francophone Mobility Program, CRI has brought in workers from countries including Morocco, Cameroon, Tunisia, Algeria and Senegal.

The demand for skilled foreign workers is inevitable in a tourism destination such as Whistler. Indeed, the 2021 census report on the resort’s immigrant community totalled 3,320, or 23.7 per cent of the permanent population (13,982).

That growing diversity comes as systemic pressures continue to bear down on Whistler, like they have in resort communities across the globe, threatening to fray the social fabric that ties the community together.

Kira Grachev, community outreach coordinator at the Whistler Multicultural Society (WMS), aptly puts it: “As the economic pressure of Whistler has increased, so too has the disintegration of the community.”

It is undeniably harder to foster a sense of community when you are living paycheque to paycheque, the cost of living continues to escalate, and the housing market is as tight as it’s ever been. Navigating this crossroad is not an isolated Whistler problem, but there is more to be done to support the so-called “invisible immigrants” and newcomers, working behind the scenes as hotel maids and chefs and home cleaners, that allow Whistler to function.

“Without them, there would be no Whistler,’’ says WMS programs and managing director Carole Stretch.

At the end of the day, immigrants and newcomers are, like anyone, trying to make a home for themselves, and a ski pass may not always be enough for them to acclimatize. Far from home and family, people can feel alone without a strong social network and community to belong to, and mental health and well-being can deteriorate as a result.

As Stretch explains, there are definitely “gaps through the net for people to fall through.”

Luckily, some of these gaps are being filled. Khadija Oubihi immigrated from Morocco to Whistler in 2018 as a chef for the Fairmont Chateau. If voices could smile, hers definitely did as she recounted her journey. “It was not in my plan to come to Canada, but I think it was my destiny. I have found myself here,” she says.

Everything was new, but she was up for the adventure. At the Fairmont, she found an employer who guaranteed her housing with two other Moroccans, security and familiarity that has allowed her to continue thriving in her new home. She made new friends, got into the prototypical Whistler activities, and found her voice, adapting to this changing landscape.

“The hotel is run by immigrants,” she says of the Fairmont. “There are Koreans, Indians, Filipinos, Australians, Japanese, Nepali, Spanish, Mexican. And of the people I work with, two people are from Canada.”

Such is true in other resort businesses, too. Head to the bank, the grocery store, the restaurants, and chances are high you will interact with someone who is a local now but has not always been. With a multiplicity of people comes a sundry concoction of experiences, some positive, such as Oubihi’s, others perhaps not.

Kapil Chopra came to Whistler in 2019 to work at the Four Seasons, after having worked at other Four Seasons hotels in Ireland and England prior to that. No stranger to working abroad, he highlighted housing instability as a central difficulty in his transition to Canada.

“There was no way I could afford a flat or apartment there with my family, so I came here five months before my wife and daughter to look for a place,” he says.

Fortunately, Chopra got lucky.

“As per my contract, I was supposed to get accommodation for two weeks, but they gave me three months for free. There were always more employees than rooms, and it was a very transient population of people, especially from the Commonwealth countries—English, Australian, New Zealand—probably because it was easy to get a visa—so we had to change rooms sometimes, but we still got housing,” he says. “It was very kind of them and I feel very lucky.”

Housing is challenging for virtually everyone in this part of the world. But, of course, a home is not limited to a roof and a place to sleep; it also encapsulates the community we interact with. Feeling at home will require more than just housing policy; it will require curiosity and sensitivity.

To help smooth the transition, the WMS team offers settlement services and community-inclusion initiatives to immigrants and the wider resort. In a town where housing is tight, the population is transient, and there are few places of worship for non-Christians, it often “becomes up to the immigrants and newcomers to create a space for themselves,” says Grachev.

When I asked Oubihi what advice she had for newcomers integrating into the community, she had a simple and efficient response: “Don’t be shy. Be brave and say what you want to say. I was shy in the beginning but then I noticed that it was not working, so I just started talking. Also, give yourself a chance to live here and try to be open, make new friendships.” A little self-confidence and a lot of courage can go a long way.

When I asked Chopra his advice on immigrating, he says to make sure you “do your homework” before you come. “Canada is very far from everything, so you cannot just hop over and then hop back if you don’t like it. It is not cheap, and flights are long,” he says.

Chopra recalled a story of a co-worker at the Four Seasons who left shortly after starting the job due to depression, homesickness, and “not being able to connect with anyone.

“It is absolutely beautiful to be here if you are an outdoor person, but if you are a city person, maybe think about what kind of activities you want to build your life around,” he adds.

Oubihi also had some advice for visitors who depend on immigrants to make their stay here a memorable one.

“We are workers providing you with a service. We work hard to satisfy our clients, and that is normal. But some customers do not think twice when they interact with us, and it becomes only about money and a service. Ask gently—a nice please or thank you makes a big difference,” she says.

Given the tourism rebound emerging out of the pandemic and the longstanding labour shortage that has impacted Whistler, often there isn’t time for frontline workers to forge the kind of community connections that would lend them a stronger sense of belonging.

Chopra, who describes himself as a “people person,” says he has felt a lack of emotional connection to his peers.

“You cannot really control who comes and goes, but if you find your people and you feel like you belong, you often stay for them. It is hard to do this here because there is no time,” he says. “I cannot attend all the community events or attend all my cultural festivities because I have responsibilities that I cannot just leave. They are relying on me.”

These gaps are where, as a community, we can pay more attention. As Oubihi says, “Some more respect, some more appreciation, this helps more than you know.”

The WMS recently published the results of its 2022 Anti-Racism, Bias and Discrimination survey for the Sea to Sky, showing that no community is immune to the prevalence of racist or biased attitudes. The scope of the study extended across the corridor, with 43.5 per cent of respondents living in Whistler. Racism is defined in the study as “unfair or harmful assumptions, beliefs, actions, behaviours, policies and/or practices that target and/or disadvantage you based on your race, ethnicity, or status as a person of colour.”

Overall, 39 per cent of respondents reported experiencing racism, bias and discrimination in the time they’ve lived in the Sea to Sky, and that number goes up once broken down into subgroups. Seventy-two per cent of those who identified as racialized reported experiencing incidents of racism, bias and discrimination. All of those identifying as Black or of African descent reported experiencing racism, bias and discrimination, and 94 per cent of those identifying as Indigenous. Eighteen per cent of those identifying as white said they had experienced the same.

Seventy-two per cent of non-white respondents said they had been subject to racism, bias and discrimination in the Sea to Sky, while every respondent who identified as Black and 94 per cent of Indigenous participants answered “yes” when asked if they had experienced racism.

The survey found the most common type of racism reported was verbal (i.e. racist comments, questions, microaggressions), followed by institutional racism, non-verbal and virtual (online) racism. Twenty-three per cent of respondents shared that they would not report the incident, which is not surprising given that the post-reporting sentiment is so often that, “nothing was done to investigate or move [me] to a safer environment,” according to one anonymous respondent.

“Sometimes it’s best to ignore,” said another respondent when asked who they would feel safer reporting incidents to. Another anonymous interviewee of the WMS survey shared, “I’m sick of the lack of diversity in Whistler. There are no black or brown teachers or principals, we just need to start hiring and centreing more people of colour.” As per the report, further education, reviewing laws and legislation, building awareness and understanding, restorative justice, criminal penalties and police involvement should be prioritized when creating protocol to respond to incidents of racism in the Sea to Sky region.

One of the takeaways from the survey was the need for more formalized channels for people to report instances of racism and discrimination locally beyond the police, and the WMS is now at work developing guiding protocols that could support both individuals and service providers in the wake of racist incidents.

Fortunately, there are several stakeholders and local organizations working to create a stronger sense of belonging for immigrants, newcomers and longtime residents alike: the local government, which recently announced the creation of a new municipal division dedicated to strengthening Whistler’s social fabric; for-immigrant organizations like the CRI, and community builders like the WMS. Amongst the array of initiatives the society offers newcomers are the Immigrant Peer Educator and the Parenting in Another Culture programs. The WMS also recently secured funding to work with employers and temporary foreign workers to educate them on their rights and freedoms as new members of their communities.

But with Whistler’s invisible immigrant community, Stretch foresees a challenge in “finding a way to reach people outside of their workplaces, the ones who are hidden, and especially reaching the ones who are not aware of their rights.”

It’s by no means easy or simple work, but if, as a community we can strive to open our arms wider to newcomers like Oubihi and Chopra, they hopefully won’t have to grapple so hard with their triple-black diamond runs into social inclusion.

For more information on WMS programming, and to find the results of its recent anti-racism survey, visit wms.wmsociety.ca.