Dinner is a distant memory when the rain finally stops. Immediately, a platoon heads toward a rack of canoes for an evening paddle. It’s the golden hour in Ontario’s lake country—when the wind has blown itself out, the water gone still and numinous, the forest lain quiet. A pause that awaits the night world.

When darkness descends, I join Algonquin Wildlife Research Station (AWRS) biologist Patrick Moldowan and several student assistants on a hike to nearby Bat Lake to see what a day’s rain has stirred from the forest floor. Sure enough, following an urge to return to water to breed that dates to their emergence onto land some 395 million years ago, amphibians are on the move. Yellow-spotted salamanders, seemingly painted so, and their blue-spotted cousins, speckled like old enamelware, are joined by more familiar hopping forms—wood and green frogs, American toads, and even a tiny spring peeper whose sticky toe-pads allow it to clamber over a low fence encircling the lake that stops the rest of these denizens in their tracks.

Patrick is conducting a long-term population study of the yellow-spotted contingent—the number of males versus females, their respective rates of return, where females deposit eggs, and how many of these result in larval salamanders successfully metamorphosing at summer’s end. This logistical feat requires marking every new individual headed for the water, as well as identifying returnees from past years, each night and morning over the course of a month-long spring breeding period. With the bottom of the knee-high fence dug into the forest floor, migrating animals encountering either side must alter their trajectory to walk alongside it until they stumble into moss-filled boxes where they can be counted. Though “drift fences”—named for the catch-all drift nets employed in open-ocean fishing—are typically made of black construction plastic, Patrick’s long-haul version features more durable sheet metal. That doesn’t, however, make it problem free. “You find out how many trees actually fall in a forest when you put up a drift fence,” he notes.

It’s late in the breeding season, so outbound amphibian traffic is heavier than the stragglers heading in. Celia, a University of Toronto undergraduate excited to experience a few days of fieldwork, sweeps ahead of us on the inside of the fence with headlamp and bucket, an eagle-eyed scanner quick to pick out cryptic forms on the forest’s variegated floor. In half an hour she plucks up over 100 salamanders—more than the average person would see in several lifetimes.

“You’re pretty calm about all of this,” says Patrick after she returns from the dark with yet another bucketful of the colourful creatures. “I’m actually screaming inside,” she smiles.

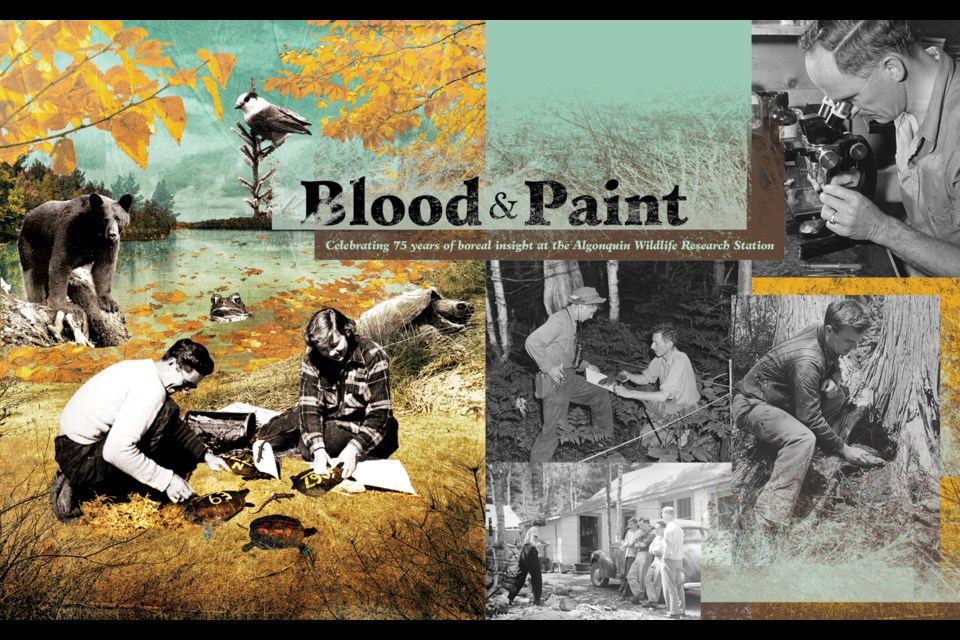

Set on Lake Sasajewun, a modest waterbody in venerable Algonquin Provincial Park, AWRS acts as a base from which researchers in sub-boreal ecosystems can access 30,000 pristine acres of park not open to the public. Since its inception in 1944 as a closed-door government facility, the station has provided scientists with logistical support in the form of accommodation, food, laboratory space and equipment. A decades-long series of funding cuts saw it morph to an incorporated non-profit in 2009 to stay afloat, but the new paradigm came with an unexpected upside—bringing the AWRS’ rich history of scientific research and natural heritage programming into the public eye.

Comprising some of the most comprehensive studies of Canadian wildlife anywhere, AWRS research has generated more than 700 peer-reviewed papers in the primary scientific literature and innumerable PhDs. Every student who cycles through contributes to one or more long-term study while also executing their own dedicated project. With generations of researchers having passed through its musty cabins, the station’s influence is impressive and lasting, with ties to every corner of the globe. Many who carried out student projects here are now globally-renowned scientists, and during three summers in the late 1940s, iconic Canadian artist Robert Bateman studied small mammals here while also honing his painting skills. The results for aficionados of Canadian art and iconography have been impressive.

Most AWRS long-term ecological studies—from snapping turtles (50 years) to spotted salamanders (24 years) to small mammals (70 years) to the Canada jay (54 years)—have been underway since before climate change came onto the biological radar, fortuitously providing baseline data against which recent trends may be measured. The Canada jay study, for instance, is one of few globally where a clear mechanism of precipitous decline—early spring thaws that effect food availability for hatchlings—is directly attributable to climate change.

Other long-term studies reveal the kind of mysteries that justify such patient data-gathering. In 2018, an enormous male snapping turtle, first captured and marked at age 40ish in 1979 and last seen in 1996, made its first reappearance in 22 years, age 80ish. Where had it been? What had it been doing?

Though out counting salamanders until 1 a.m., I’m up early to meet grad student Chris Angell, who I find seated outside a small, barn-like laboratory. Chris studies antler flies and is happy to share arcane details both biological and empirical. These tiny, grain-sized insects spend their entire lives on, or near, a single antler left behind by rutting moose. Chris’ work begins when he labels flies with different-coloured symbols using a single-bristled brush. Once able to be identified, the flies are released back onto their home antler for observation. On the horn’s surface they forage for food, defend territories, and mate; females lay eggs in cracks in the antlers, where larvae hatch and grow within the spongy matrix of mineral-rich bone. When ready to pupate, the larvae emerge, leap off the antler, burrow into the forest floor, and emerge 10 days later as adults who then return directly to the same antler. This odd, spatially limited existence allows scientists like Chris to study everything in the insects’ lives—from sexual selection to aging. And, like other marvels of the boreal forest, the antler fly and its cradle-to-grave world were first described at AWRS.

Today, Chris and his assistants are wrapping moose antlers in tinfoil. They’ll weigh the amount of foil it takes to cover one, then compare this to the weight of a known area of tinfoil (e.g., a 1 x 1 metre square) to estimate the antler’s total surface area. Given the strips of red tape used to secure foil to antler, their efforts resemble the preparation of garish Christmas presents of quintessential Canadiana.

Meanwhile, antlers arrayed on the ground outside are hosting a party. Awakened by rain, the tiny larvae—resembling small, translucent pieces of thread—are collecting at the antler’s tips and flinging themselves into the litter. It’s actually both moisture and sound that are required, so when larvae are needed during a dry spell, Chris simply recreates the combination by spraying water on the antlers and drumming on them with sticks. The Pied Piper trick works, and the larvae always emerge.

The AWRS nerve-centre is its whitewashed and red-trimmed cookhouse, containing four eight-person dining tables, a few ratty easy chairs and couches, a small upright piano, guitars, and a stack of games. In addition to a glut of field guides and rainy-day trash fiction, bookshelves sag with the faded yellow spines of National Geographic, as well as arcane titles like The Search for the Giant Squid, and Patterns of Reproductive Behaviour. At the Formica table where Patrick and I eat a lunch of curried lentil soup and bannock beneath a wall of station alumni photos, we share our space with a dog-eared deck of cards, someone’s origami experiment, a worn map of Algonquin, and a box of assorted wingnuts.

Although it’s in the business of investigation, the vagaries of AWRS require no discussion, such that when the girl who sits down next to us with red streaks on her hands is casually asked “Is that blood or paint?” her reply of “Both” is absurdly truthful: she’d been taking blood samples from turtles and painting numbers on their shells for an upcoming study when things in the lab got messy. “I tried to clean up the paint because it looked like a murder scene,” she offers earnestly, “but now it just looks like someone tried to clean up a murder scene.”

Patrick offers a halting chuckle as he spoons the last of his soup. Among a dozen other responsibilities, including running AWRS’ social media, he was in the throes of planning its 75th anniversary celebration, a September weekend of events to be attended by old timers including a sage 88-year-old Robert Bateman. But, of course, he was also in the midst of the yellow-spotted salamander breeding season—the juggernaut in his juggling routine.

During that morning’s shift at the salamander fence, the weather had been clear, Patrick’s team particularly cheery. Working when it was dry was surely a treat, but you also notice more when you are undistracted by precipitation—the emerging ferns, the carpet of wintergreen, and the downed wood demarcating the springtime forest; the songs of returning birds, the busy squirrels, the squish of bog under someone’s boot. Collectively, these paint a picture of the opportunity experienced by all who had tread here over the years. Three-quarters of a century on and there was still plenty of data being gathered. But it was the learning inherent to the process, the inculcation of a lifetime of reverence and stewardship for the near-north environment heard in students’ voices at the fence—happy, upbeat, excited, curious.

It seemed like that alone was worth 75 years of effort.

You can find out more or donate to Algonquin Wildlife Research Station at algonquinwrs.ca