So many of the stories non-Indigenous Canadians hear about its First Peoples are couched in trauma. Anytime we talk of Truth and Reconciliation, troubling tales of racism, violence and systematic oppression are usually never far behind. Of course, these are stories that need to be told and heard, and last summer’s discovery of the remains of 215 children in Kamloops that finally opened many Canadians’ eyes to the horrific legacy of residential schools in this country is all the proof you need of that point.

But in Indigenous Canadians’ fight to reclaim and preserve the culture and traditions that were so callously ripped away from them, there are also stories of perseverance, pride—even joy—that are just as important, if not more, to share with the world.

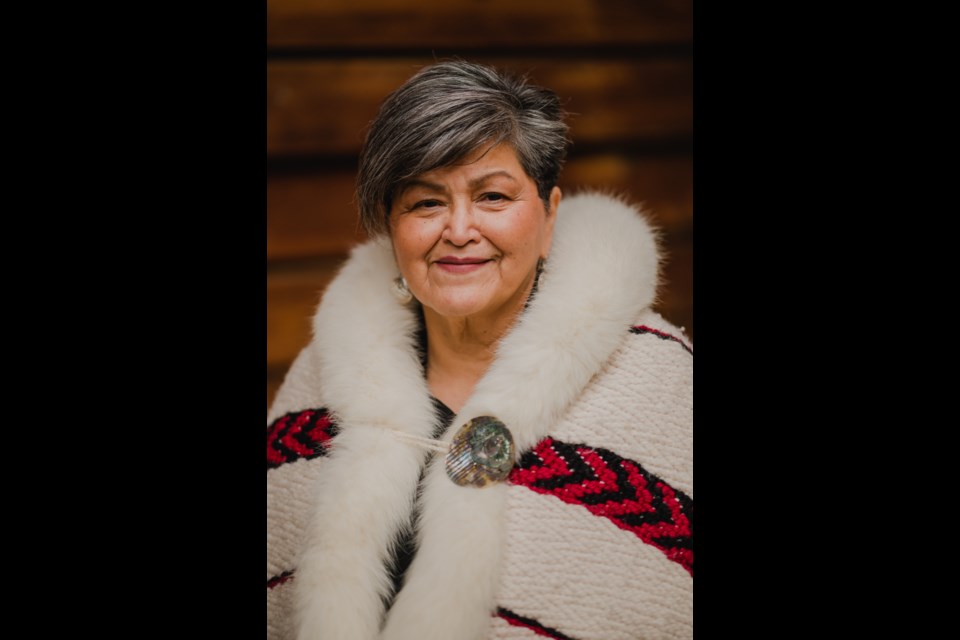

That’s the main thing Squamish Nation Chief Chepximiya Siyam Janice George hopes guests take away from a new exhibit at the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre (SLCC) celebrating the vitality and diversity of First Nations’ languages across B.C.

“It’s so important for people to understand how we are working at getting back our language—and not just working at it, but being successful at it,” she says. “It’s not just a sad story. It’s an amazing, happy story that we are positively moving forward and taking everything back that our ancestors lost. We have to remember that.”

“Our Living Languages: First Peoples’ Voices in BC” is a travelling exhibit from the Royal BC Museum, in partnership with the First Peoples’ Cultural Council, that showcases how Indigenous communities across the province are working to ensure their respective languages survive and flourish. All 34 of B.C.’s distinct Indigenous languages are featured—including Ucwalmícwts, spoken by the Lil’wat, and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim, spoken by the Squamish—and visitors will encounter interactive stations, video and audio that guides them through the history of disrupted languages in B.C., teaches them about the nuances and complexities of the respective languages, and captures the efforts being made to document and revitalize them.

“A lot of Indigenous languages have different punctuation or different [alphabets], and it explains what those different [alphabets] are and just gives one example of what it sounds like,” explains SLCC curator and Lil’wat Nation member Mixalhítsa7 Alison Pascal.

One of the most frequent questions staff at the SLCC get asked is about the “7” used in both Ucwalmícwts and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim, which the exhibit explains in detail. (For the record: the 7 indicates a brief pause, technically known as a “glottal stop,” between syllables. Elder speakers developed the character with linguists in the late ’60s as the oral languages were being translated into written form.)

“It relies heavily on listening stations to really bring the language alive,” Pascal adds.

In many ways, the Lil’wat are ahead of the curve when it comes to preserving and nurturing its language. For years, the Xet̓ólacw Community School has offered Ucwalmícwts as a second language class to young learners, thanks in no small part to the efforts of Lil’wat linguist and professor Dr. Wanost’sa7 Lorna Williams, who helped establish the Mount Currie school—only Canada’s second band-run school—in 1973. Considered one of the world’s leading experts in Indigenous language revitalization, the Order of Canada recipient often holds up the Lil’wat’s tireless efforts over the years as an example to other Indigenous communities looking to preserve their own native tongue.

“I had the privilege of being immersed in my culture, so I use it as an example to help people look at their own. For example, at UVIC, I developed a course called ‘Learning and Teaching in an Indigenous World,’ and I used the concepts of teaching and learning from Lil’wat,” Williams told Pique in an interview last summer. “It was to encourage people in other languages to look inside their own language for those concepts. It’s really been an anchor for me, so I share it in that way.”

Partly an effort to have more adult speakers for young Lil’wat to practise the language with, at the Ts̓zil Learning Centre in Mount Currie, Ucwalmícwts classes have begun being offered for adults as well in recent years.

The Squamish Nation has also made significant progress in preserving and nurturing its language, but without its own school like the Lil’wat, the Nation has had to partner with educational facilities outside its territory. Squamish Nation Councillor Khelsilem has been instrumental in the work that has been done; in 2016, he partnered with Simon Fraser University to found a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh snichim immersion program that has since taught the language to dozens of Squamish Nation members—including two SLCC staff who are looking to join the course this spring.

“It’s a huge benefit to have more of those young people, who work with other young people, speak the language and encourage their peers to join in,” Pascal says.

Just like the Living Languages exhibit itself, technology has been a vital tool in teaching and expanding Indigenous languages throughout B.C., particularly for the young speakers of tomorrow.

“I look at my grandsons and they are always on their phone or computer or playing games. Having more would be even better, if we had more virtual language games and things like that,” says George. “We have to do it. It’s important and that’s the language of our kids now.”

Online tools have also helped facilitate broader access to remote learning, a crucial lifeline for the thousands of Indigenous British Columbians who have been squeezed out of their communities.

“Most Indigenous communities, the amount of land that they have was drastically reduced when Canada was a new country. The government, as a rule of thumb, only gave Nations something like 15 per cent or less of what they originally had,” she explains.

Reserve land was carved out to only accommodate what were already dwindling population numbers in many Indigenous communities of the day, ravaged by disease and conflict brought in by settlers, leaving little room for population growth. On top of that, oppressive restrictions put in place meant expanding that land was (and in many ways, still is) virtually impossible.

“So having the ability to provide this learning is really important because in our own community, we can’t house everybody. “It’s just not possible with the population boom,” Pascal says. “Once you leave the reserve, the ability to connect with language teachers is really difficult. So being able to go online and [learn] it is so crucial.”

“Our Living Languages” in on now at the SLCC until May 23. Learn more at slcc.ca/exhibits/our-living-languages.