Curtis Collins, director and chief curator of the Audain Art Museum, is standing in front of a drawing of a nondescript building by Inuit artist Itee Pootoogook.

The clean lines and simple colours might be appealing, but there’s a deeper meaning to the piece.

The building depicted is the West Baffin Eskimo Cooperative, a printmaking and stone carving studio founded in 1959 that also operates as a retail centre, gas and water delivery point and community hub in Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset).

“All of the printmaking you’ve ever seen from the 1960s forward, most of it has come out of this very modest façade,” Collins says. “It really kind of captures the essence of the show. In the ‘60s, the artists would do drawings, give them to the printmaker and then that printmaker would interpret the drawing both in light and colour and the print would come up. So there’s a massive bank of drawings that nobody’s ever seen because they only come out in the South in the form of prints.”

That’s part of the appeal of a new exhibit at the Audain Art Museum—one of two that opened on June 10 and run until Sept. 6—focused entirely on Pootoogook's drawings.

Hymns to the Silence features 60 coloured pencil and graphite drawings on paper, offering a quiet, contemplative look at Pootoogook's Arctic. The retrospective was guest curated by Dr. Nancy Campbell, with both new exhibits organized and circulated by the McMichael Canadian Art Collection.

The pieces range from portraits to landscapes to scenes of life around his home; a tarp frozen in a compelling shape, the head of a walrus on a bed of rocks with a pair of boots behind it, a group of women stretching polar bear skin. There are also a handful of abstracts.

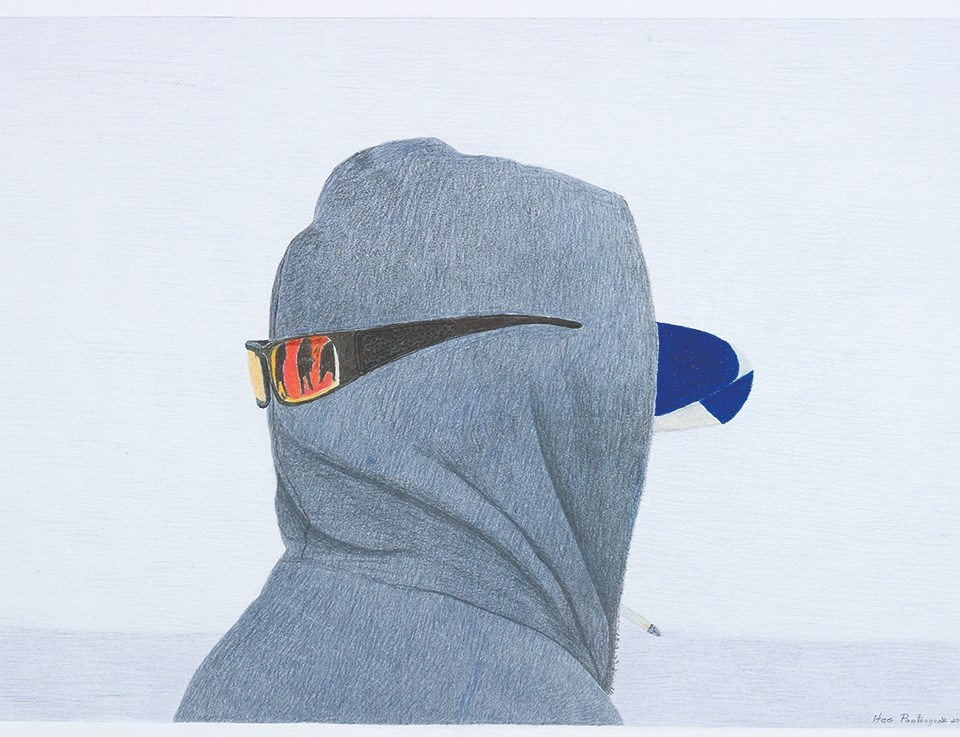

“The show was organized in thematics and while Itee is not particularly known for his figurative work … we thought that this was a good way to introduce him,” Collins says, stopping in front of a drawing called Untitled (Man With Hoodie and Sunglasses).

As the name suggests, it shows a person in a grey hoodie with sunglasses perched on the back of his head, a mittened hand blocking the sun from his eyes, though the face is obscured.

Collins’ favourite drawing in the exhibit is Electric Lamp, which depicts a light pink lamp against a mint wall, resting on a table, with just the corner of an electrical socket showing.

“It’s a very simple, ordinary lamp, but just the colour combination and this really strategic detail, just placing that little plug in the corner, causes a little tension and offsets what was totally a symmetrical thing,” he says.

The second, slightly smaller exhibit on display is Louie Palu: Distant Early Warning.

The award-winning photographer travelled to the Arctic on a fellowship from 2015 to 2018, which eventually turned into an assignment for National Geographic magazine to capture militarization in the North American Arctic—particularly what’s left over from the Cold War.

“The distant early warning system … that was set up after World War Two as part of the listing posts across the Arctic because the threat then was the USSR was going to come over to the Arctic and bomb us into submission,” Collins says.

While the medium is different from the Pootoogook show, so is the overall impression of the Arctic. The images capture an outsider’s perspective and, while compelling in its own right, they feel somehow colder and lonelier.

“It’s predominantly somewhat of a documentary-style photographic exhibition, but there are moments in it—like those two figures—that … play against it,” Collins says, standing next to an image of two people, back to back, in green, fur-trimmed parkas with red hoods.

The show is filled with snowy, bleak images that are at once beautiful and intriguing. Red-stained snow blocks mark an “X” for a helicopter landing, men in yellow dry suits swim through mostly frozen water during ice training, and a group of parachuters float above snow-caked mountains.

“It’s interesting how this photo documentation plays off of Itee’s renderings,” Collins says. “It makes a nice relationship, but it’s a very different perspective from someone who’s raised there, whose ancestors are from there, versus someone who is parachuting in—just the different approaches to the landscape.”