A Canadian study suggests children who were not breastfed while receiving antibiotics in the first year of life had triple the risk of developing asthma because they lacked specific protective sugars found in human milk.

Dr. Stuart Turvey, a lead researcher, said antibiotics such as amoxicillin are commonly prescribed to treat a wide range of infections in young children, but the medications have also been linked with disrupting the development of a healthy gut microbiome.

"What we've known for some time was that babies that got antibiotics early in life were at higher risk of having asthma at school age and beyond but no one knew why," said Turvey, a pediatrician at BC Children's Hospital.

The study, published Wednesday in the journal Med, found that sugars in breast milk, which make up about 20 per cent of its indigestible carbohydrates, promote the growth of the B. infantis bacteria to help make other bacteria in order to train the immune system and prevent the development of asthma and allergies.

Researchers also said they identified the breast milk sugars that offer this protection, which could potentially be used to supplement formula for infants that need antibiotics but for whom breastfeeding is not an option.

"Children are born with pretty much no bacteria," Turvey said. "Then these communities (of bacteria) start to build, with pioneer species that help the other ones colonize. So the timing matters," he said of when people are prescribed antibiotics, which "confuse" kids' immune systems in the first few months of their lives.

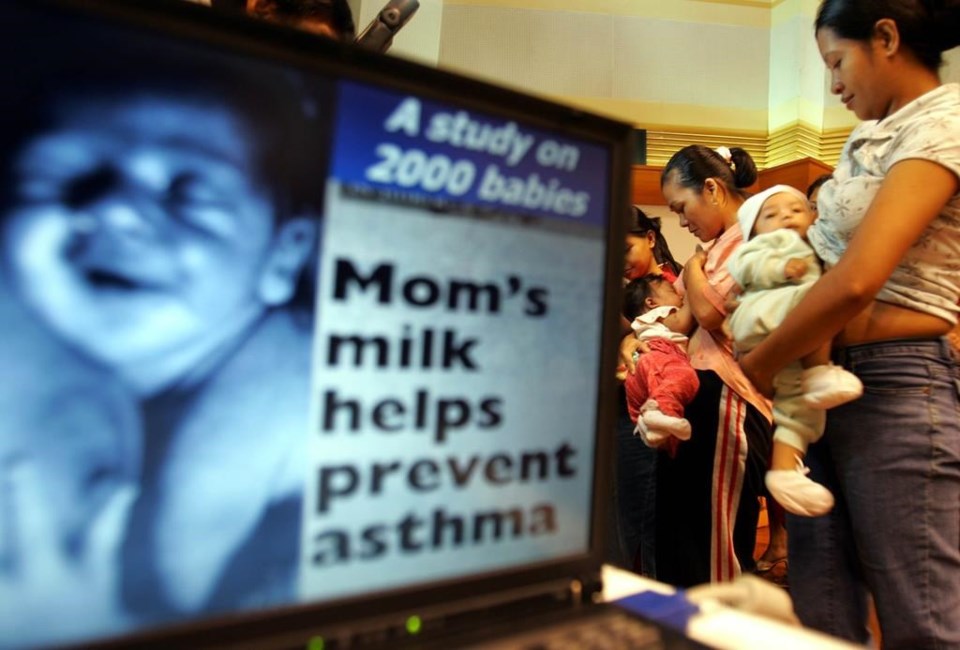

The research involved a total of 2,521 children in Vancouver, Edmonton, Winnipeg and Toronto. It showed 17 per cent of the kids received antibiotics in the first year of life.

Three groups of kids were compared — those who received no antibiotics, those who were given them while being breastfed and those who got them without being breastfed.

When a subset of 1,338 children were three months old, researchers collected a dirty diaper to test the stool. A year later, another diaper was collected for a stool sample from the same kids, said Turvey, adding the expense of the relatively new technology prohibited all of the children's samples from being tested.

"We got the poop samples and then we did metagenomics, a type of genetic sequencing, to identify all the bacteria by the DNA that's there. This (B. infantis) came up as a really strong signal," he said.

At age five, all the children were assessed for asthma. Those who did notreceive breast milk but had been prescribed antibiotics were at three times the risk of having the condition.

"The children who received the antibiotics while breastfeeding weren't at any higher risk than the children whodid not have antibiotics," Turvey said.

"One important thing was that any breastfeeding was protective. So it wasn't just exclusive breastfeeding, with no other form of nutrition."

Asthma is a top reason for kids visiting for emergency rooms and doctors' offices, often while missing school, he said, adding that despite the findings, amoxicillin is a potentially life-saving drug for very young kids.

The study findings could spur clinical trials to determine if the natural sugars in breast milk can be used to supplement formula for the benefit of people who can't breastfeed their children, Turvey said. Chemists could make synthetic versions of the sugars, similar to some that are already in formula, he added.

"More knowledge about the protective ones could inform that process."

Ailbhe Smyth, a volunteer with a Vancouver chapter of La Leche League, which supports breastfeeding mothers, said those who are struggling with what is often a challenging experience, as it was for her, should not take the findings as another reason to feel guilty about being "a perfect parent."

Fewer public health clinics were offering support through lactation specialists even before the pandemic and some women are opting for private consultants to avoid long wait lists, Smyth said.

"But that's still a barrier. Some people just don't have the extra money to do that," she said, adding: "I think support doesn't only need to come from the health-care system because it has to come from society in general."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Jan. 5, 2023.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

Camille Bains, The Canadian Press