My son heads off to kindergarten in September. Game-changer, friends say. You don't get as much time as you think, say others. I can't wait to learn to read, he says. What just happened to the past five years? I think.

He will catch the school bus, from our driveway, through Mount Currie, to school. Through Indian Reserve Number 10.

They took their children away and called it school. They shaved their heads and called them by number and beat them, and worse.

On Thursday, I sat in a room full of parents while our five-year-olds divided into three groups and sang songs, listened to stories, coloured, and I wondered which of us, me or my son, will feel the separation anxiety the hardest.

Who am I kidding? It will definitely be me.

I looked around at the parents of the Class of 2031, embarking on a 13-year journey together, thinking: We're really a community, now.

When Lorna Williams was taken away to school in Williams Lake, she was six years old. In 2015, Dr. Williams tried to explain the impact in a multimedia teaching resource. There was an impact on the individuals that attended.

"But residential schools also impacted communities because when children were removed, the communities became childless. And in the times when our communities were intact, the community really revolved around its people, and especially around children ... To remove a whole layer of society? It impacts everything."

Approximately 55 children start kindergarten at Signal Hill Elementary in September. I look around the room and imagine these 55 families suddenly being childless. I imagine walking through town at 8:30 a.m. on a weekday to silence. I imagine us turning from harried, racing-around-trying-to-squeeze-it-all-in people, to zombies.

Actually, I'm lying. I don't imagine it.

I simply can't.

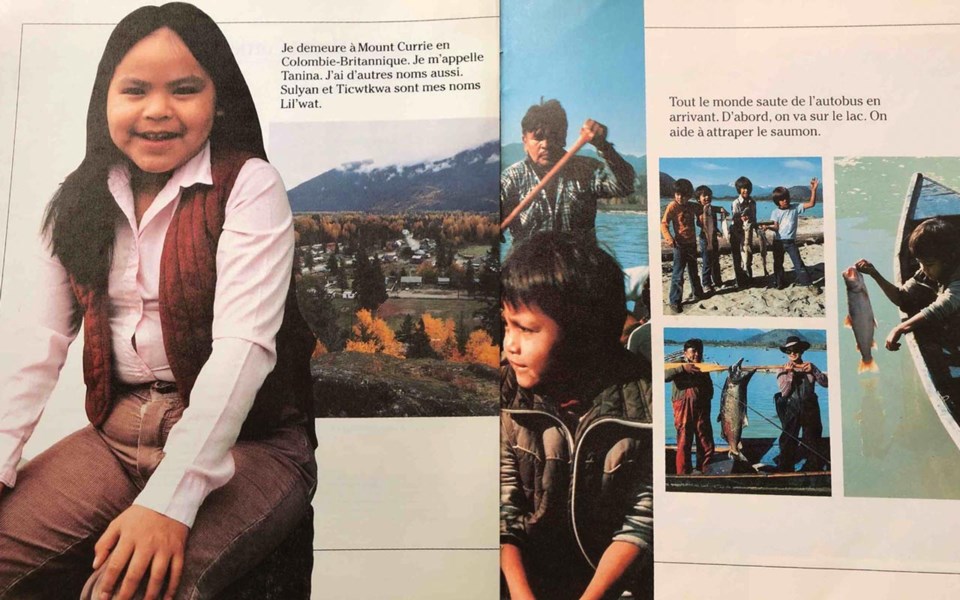

In the late 1970s, Williams wrote a book—a Grade 2 social studies reader called Exploring Mount Currie. She was invited to contribute by the publisher and pitched her idea, to write something about a current First Nations community. "I wanted to tell the story of how we live."

She was raising her daughter as a single parent, working full time, designing Lil'wat's language curriculum, helping run a school, going to school full time. And writing a book.

She came up with idea of collaborating with her niece, Tanina Williams, who was in Grade 2 herself, to tell the story of life in the community through Tanina's eyes. "I asked my brother if Tanina could be my model and he agreed."

Williams' concept was replicated across the series, but the province didn't want to publish her book. First Nations weren't really part of British Columbia, they said. Williams had just started a job with the Vancouver School Board when the book was finally published, after the province gave up a legal battle to prevent it. It was reviewed, in a two-page spread, in The Vancouver Sun under the headline, "A rosy-eyed view of an Indian reserve."

Says Williams: "They basically said that my book was fiction.

"My book about our lives, told through the eyes of this child talking about what she does in the community, going to the fish camp, spending time with her grandparents, introducing her aunty who was the director of the school, and her father, who was a bullrider, just being a child. And they wrote that it wasn't the reality."

She called her brother to warn him about the story. "I wanted to prepare him, because his face was there, in the newspaper. Tanina's face was there."

At the other end of the phone, she could hear her brother explaining it all to Tanina, who'd been excitedly asking, "Is it about our book, Daddy? Is it about the book?"

"And then I heard her say, 'Are they saying we're not real?'"

For many years, the school curriculum has insisted that Tanina and her family and her culture, existed only in the narrowest sense. "Our stories, as told by us, have not existed in the school curriculum," said Williams.

What we learned about ourselves was filtered through a European mindset and it caused a sense of invisibility and a sense of non-existence and a devaluation of our way of life, our knowledge, our wisdom. There's such a distrust of our stories because there's still a real belief that our knowledge and wisdom, our languages, our way of life, our values, are not good enough, they're not civilized and sophisticated enough, for the world today."

That is changing. My son starts school under a new curriculum. A curriculum that has come about thanks to the work of Williams, and people like her.

In 2010, Williams introduced an audience of educators to one Indigenous word: Stucum. "Stucum in my language is a very special word. It's rarely used today, but I've always loved this word. Stucum is what people would say to each other when someone was going on a journey. Stucum Wi means to let the creator help you see your path. As humans, because we have such a wonderful brain, we think that it can do everything. But it's important that we remind ourselves that we need help. Acknowledging that sometimes we need help to see the path is ... important when we're walking together."

I grasp onto this word like a gift to my future self, a woman standing at the bus stop, letting go of a small boy's hand, releasing him into the world, onto the path that awaits him. Stucum. Stucum Wi. May the creator help you see your path. May you find help where you need it. May we all walk towards wisdom together.

The Velocity Project: how to slow the f*&k down and still achieve optimum productivity and life happiness.