A B.C.-based non-profit has received $60 million to work with some of the world’s top clothing and publishing brands to decarbonize their supply chains and avoid sourcing wood from ancient forests.

Headquartered in Vancouver, Canopy already works with 900 companies, including some of the world’s top brands like H&M Group, Zara, Walmart and Penguin Random House.

The latest injection of funding, which comes from the TED Talks-affiliated The Audacious Project, will more than double the group's resources, and allow it to expand several regional hubs around the world. Those hubs will have the goal of sourcing more than 60 million tonnes of low-carbon fibre — largely through the recovery of textiles and waste food destined for landfills or agricultural residues that would otherwise be burned.

Instead of trying to change the behaviour of eight billion people on the planet, Canopy focuses on how companies source over five billion trees per year to produce pulp, paper and wood-based textiles like rayon and viscose, said Nicole Rycroft, the group's founder and executive director.

“We're looking to reduce that number by a third by 2033,” Rycroft said. “This is a really a game changer for us.”

Over the coming decade, she says Canopy will act as a global and regional hub to galvanize companies to make their supply chains more sustainable by eliminating the sourcing of wood fibre from all high-carbon, high-biodiversity forests.

The organization will also continue to push institutional investors like pension and sovereign wealth funds to invest an estimated $78 billion required to build new infrastructure and wean companies off unsustainable forestry products.

The technology and ideas to replace wood fibre with recycled or alternative materials is already there. Take fashion: roughly 100 billion items of clothing are produced every year, and 60 per cent of those end up in a landfill within 12 months, Rycroft says.

Next generation fibre manufacturers are already getting off the ground in some countries that have historically relied on forestry as a major economic engine. Halfway up the east coast of Sweden, an old pulp and paper mill in the city of Sundsvall is currently being transformed from a consumer of wood fibre to one that ingests old T-shirts and blue jeans.

Canopy helped the Renewcell mill secure finance for its transition. For every tonne of clothing pulp produced, the mill is expected to use 90 per cent less water, half the energy and emit five tonnes less carbon compared to the a conventional wood mill, a pilot mill showed.

“It's re-employed 100 people that had previously lost their jobs,” said Rycroft.

Rycroft says there are already a number of innovators looking at old, shuttered mills in B.C. as a possible place to launch operations.

Other projects Canopy is looking to back include facilities and systems that produce fibre from microbial cellulose grown on industrial food waste. And then there's straw, which is regularly burned in huge quantities in places like India, contributing to a significant health crisis and adding carbon to the atmosphere.

“We have mountains and mountains of straw,” Rycroft said. “Here in Canada, we have 50 million tonnes of straw leftover after the green harvest every year. Even if you set 50 per cent of that aside to maintain the organic integrity of the soil and for animal bedding, that still leaves a lot of fibre to be able to displace the pressure on forest by actually using straw to make packaging.”

By 2033, the creation of next generation fabrics and paper is expected to avoid the release of 1.3 billion tonnes of emissions — twice that of Canada’s annual output — and totally eliminate the use of virgin forest fibre currently used in the paper packaging and fashion industries, Canopy claims.

“The numbers sound a little ridiculous, but it's anywhere between an 80 to 120 per cent drop in greenhouse gases, and that's partly because the raw material that products are coming from is actually where there's an incredible concentration of biogenic carbon.”

Swapping plastics for wood could be disastrous for forests and the climate, say critics

As Canopy works to push supply chains away from forests, some sectors are pushing to swap petroleum-based products for wood products like those increasingly found in low-carbon building material.

By dropping fossil fuel-based materials for wood, the carbon in a tall timber building or piece of furniture stays locked out of the atmosphere for generations, the thinking goes.

But according to the Wilderness Committee’s national campaign director Torrance Coste, that calculation often fails to consider the carbon released when forests are logged.

“We're seeing a huge push from the forest industry to market wood-based products as green alternatives, the argument being that they're made from renewable trees as opposed to oil-based products. Everyone knows wood products contain carbon, so that's carbon that's out of the atmosphere, right?” Coste said.

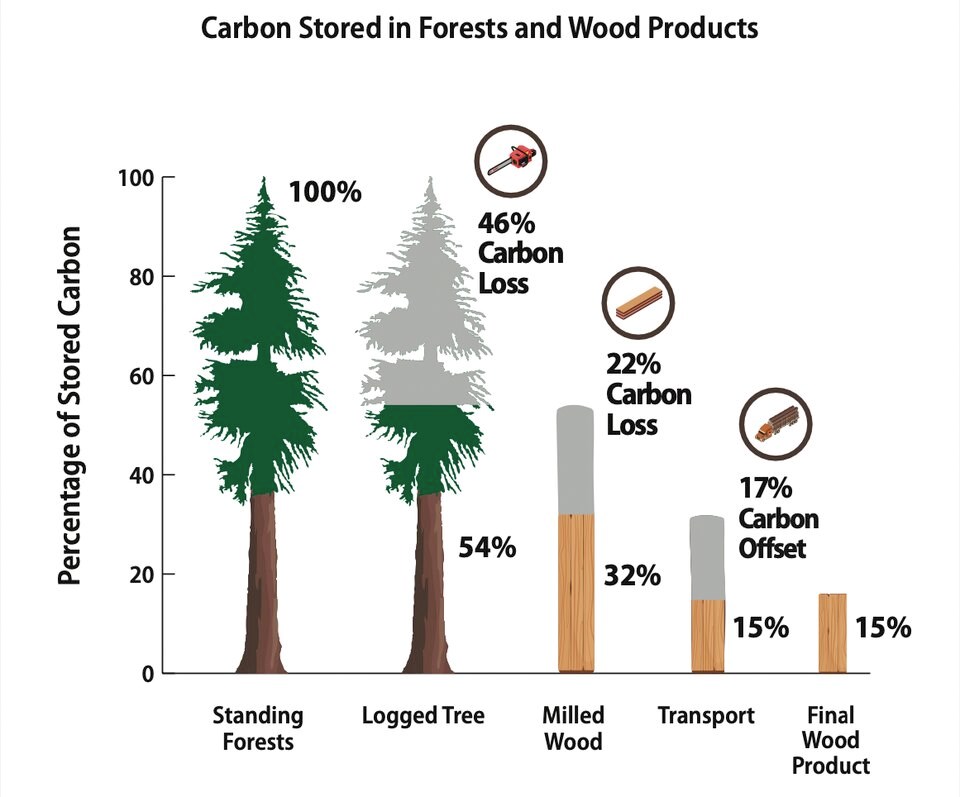

“The problem isn't that this is untrue, just that it's only a small part of the story: yes, there is carbon stored in your dining room table or that new mass-timber apartment building in your neighbourhood, but it's just a fraction of the CO2 that was held in the forest that wood was standing in, with the remainder being released into the atmosphere in the process of extracting and processing it.”

Across the world, forests absorb an estimated 7.6 billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide every year. But logging, wildfires and city building threaten that carbon sink.

In Canada, those forces have combined to make forests a net source of carbon since 2001, according to the federal government. But critics say the government has failed to account for millions of tonnes of emissions produced from the logging industry.

A report last year from Nature Canada and the National Resources Defense Council found Canada’s national emissions inventory failed to account for 75 megatonnes of emissions produced by the logging industry in 2020 — roughly equal to the greenhouse gases produced by the Alberta oil sands.

An audit report released this week by Jerry DeMarco, the Commissioner on Environment and Sustainable Development, found Canada won't get even a tenth of the two billion trees it promised to plant in the ground over 10 years. And when it comes to emissions from forests, the federal government “did not clearly report on the effects of human activities on forest emissions.”

In B.C., wildfires make up the largest share of the province's annual emissions, but are not reported in the same way greenhouse gasses from logging and forest management are set aside. Since 2004, the forestry sector flipped from a net carbon sink, so that by 2018, the industry released more than half the annual emissions currently being counted in the province, according to public data.

“The B.C. government appears to be exploring ways to take credit for the carbon stored in forests here before they account for the CO2 that's emitted from them, which is a huge problem,” Coste said in an email.

Coste says including wildfires emissions in official tallies would likely need to be coordinated at the international level, as the United Nations doesn’t currently expect countries to count those emissions in their national inventories.

Emissions from the forest sector, however, “can and should be calculated and accounted for in B.C.'s climate plans,” he said.

But for Rycroft, correcting Canada's "false accounting" won't matter if it's not matched by action on the ground.

“We need industries and individual producers that are operating in high-carbon forests to actually change their practices,” she said. “We need to stop carbon going into the atmosphere at this point in time.”

“This is an opportunity for Canada to actually have an alternative.”