The girls were planning to get the old pot-bellied stove fixed.

It had been ordered and was on its way when they hired a woodworker from their school to winterize their Alta Lake cabin.

He came up with his wife and baby to stay onsite while he worked. The girls knew change was coming to Alta Lake; a ski resort was about to be built and they wanted to be able to stay at the cabin comfortably in the winter.

One day, the woodworker and his little family decided to go for a walk, leaving a fire burning in the stove—the only way to keep the cabin warm.

As they made their way up the trail they heard a loud “whoosh.”

When they looked back, the cabin was completely engulfed in flames. The bottom of that old stove had fallen out and the wooden structure didn’t stand a chance.

In the blink of an eye, Witsend was gone.

‘We never had time for fun’

The five Lower Mainland teachers just clicked.

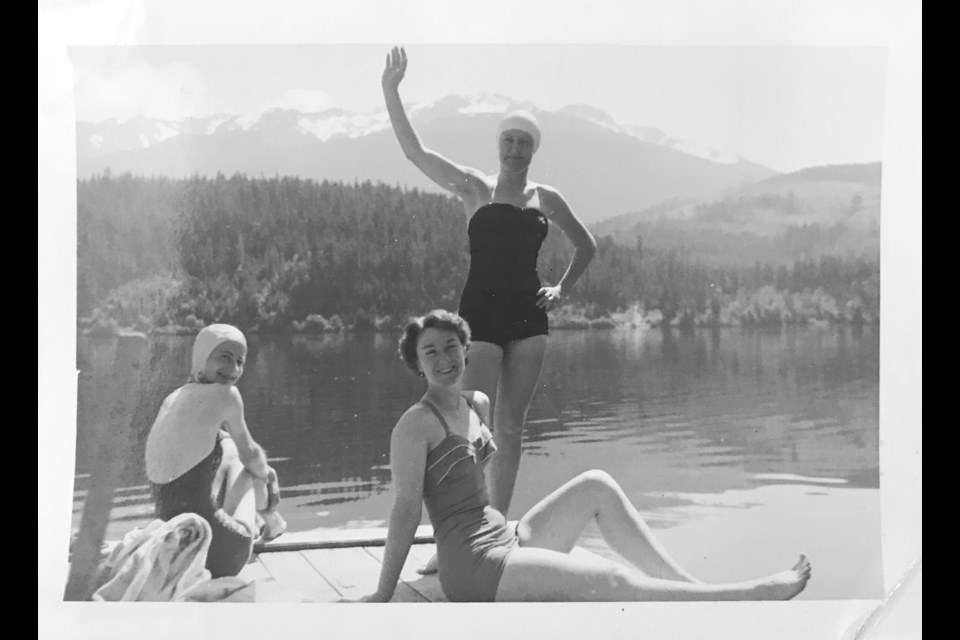

June Tidball and Florence Strachan (whose married name was Petersen) met as young teachers at Burnaby North High School. Florence, today recognized as a Whistler icon, was friends with Jacquie Pope, with whom she played on the Canadian national field hockey team, and Eunice “Kelly” Forster (later Fairhurst), also teachers at the school, while June brought Betty Gray (Atkinson), originally from Armstrong, B.C., into the fold.

As June (whose married name was Collins) put it in an oral history she did for the Whistler Museum back in 2013, the group had been working hard their entire lives: first in high school, then studying to become teachers and working at their chosen profession, as well as summer jobs.

“A lot of us had been the same kind of people,” she said. “We worked hard. We had always worked hard … We all had jobs in the summer and taught in the winter and went through school and we never had time for fun.”

That changed in 1955.

Jacquie and Kelly had been up to Alta Lake (which, for the uninitiated, is what Whistler was named prior to the late ’60s) to stay at Rainbow Lodge—owned by pioneers Myrtle and Alex Philip—and Betty had worked at the lodge during summers as a student at the University of British Columbia.

So when Betty heard Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Masson had put their simple, two-bedroom summer cottage perched above the shores of Alta Lake up for sale, the group decided to meet them and check it out.

Initially, the couple was asking $2,500, but after that meeting they “thought the girls were so nice and were going to appreciate the outdoors that they reduced the price by $500,” according to Florence Petersen’s book, The History of Alta Lake Road.

“Then, when the girls offered to pay cash, they reduced it a further $500 and this included a clinker rowboat, wharf and a toolshed with all the contents besides the furnished cottage.”

The five of them pooled together their money and bought the whole thing for $1,500. (According to various inflation calculators, that would be between $15,000 and $16,000 today.)

Back then, the cabins and homes that dotted Alta Lake all had names. It was an arduous trek from Vancouver to the cabin that helped the girls come up with theirs.

“You’d take the union steamship up to Squamish then you’d have to wait,” June said. “The train was about a couple hours later that went up to Alta Lake. So that interval was taken up by everybody running up to the hotel and getting a case of beer. [The conductor] would give two toots on the train and everybody would come running with their beer … It was a full day just to get up there. The whole trip was dramatic because you never knew what would happen on the train.” (At least once, that included a man in a coconut bra with a whisky-filled spray gun.)

After getting off the train, they had to walk half a mile along the tracks—with their luggage, food, and supplies in tow—and then, to top it all off, climb up a steep, winding set of stairs.

After a particularly rainy trek, Betty “announced she was at her wit’s end and we agreed to be feeling the same way—hence the name,” Florence wrote in her book.

On the surface, Witsend might have just been a cabin owned by five women, but it was notable for the time, as they were the only group of women to own an Alta Lake property together in the ’50s. They were also in their early-to-mid-20s at the time, when the pressure to settle down, get married, and have children must have been omnipresent. While most of them eventually married and had children, during those summers, being together and having a good time in the outdoors took priority.

In that way, they seemed ahead of their time; arguably, pioneers for present-day Whistler women, many of whom still move to the resort in their 20s to have fun and chase adventure with friends.

“I think they kind of developed their own sisterhood,” says Carol Fairhurst, Kelly’s daughter, in a recent interview with Pique. “They built some amazing memories and a very, very strong bond of friendship, with themselves, with their families. I think they probably were empowered as a group with that independence, with the ability to do something like that. There wasn’t just one of them; there were five. You’ve got that reinforcement of your independence. Those are formative years for young women—and they just had a lot of fun.”

Pat Beauregard, today in her 90s, was a friend of the Witsend girls, and confirmed they just really weren’t that worried about settling down on a timeline. Pat also played on the Canadian field hockey team with Florence and Jacquie, and travelled around the world for games.

“We had no desire,” she says of marriage. “We all played our sports. It made quite a difference.”

Although, it should be noted, Pat met her husband Denis at Witsend (Denis and other male visitors stayed in a separate “rooster’s roost” suite beside the cabin, Pat recalls) and they eventually got engaged while walking the railroad tracks after a party there one evening.

Witsend brought other couples together, too (perhaps affirming that old adage that love finds you when you stop looking for it). Florence met her husband, Andy Petersen, at the nearby Rainbow Lodge. Dick Fairhurst (Carol’s father), another Alta Lake pioneer, started out as a kind neighbour who brought the girls hot water and lit their stove on their first trip up to the cabin, helping like he did with many others in the small community. Then, a few years later, he married Kelly.

The reverberations of that cabin also had a lasting impact on what would go on to become Whistler: Florence founded the Whistler Museum and Archives, became a popular marriage commissioner and earned the Freedom of the Municipality; the Fairhursts ran the Cypress Lodge, which eventually became The Point Artist-Run Centre; on a hiking trip, Kelly helped give Burnt Stew its name before it was a ski run; and Jacquie was a fixture in the community until she moved to Squamish.

“I think they had an impact on the valley, but the valley obviously had an impact on them,” says the Whistler Museum’s community and events manager, Allyn Pringle, who has written about Witsend for the museum and grew up in Whistler. “I think it went both ways.”

Prank pullers

Once they made the full-day journey up to Witsend—often staying for most of the summer or during other school breaks—they could relax.

They went berry picking, bird watching, hiking, horseback riding and paddling. There wasn’t much developed beyond their side of Alta Lake, but occasionally they’d take the rowboat across the lake or canoe down the River of Golden Dreams.

When they came up in the winter, they would skate, play hockey, and have fires on the edge of the lake to warm up.

“I enjoyed it very much,” June said in the oral history. “It was a beautiful place. At dawn, you could see the mist on the water. It was a beautiful time to go for a walk along the tracks. There were no noises. In the evening, it was interesting to sit on the porch and watch the moon come up. In between we were swimming, rowing, fishing, hiking, horseback riding, berry picking. We were doing a lot of things. That little cabin we had was just so nice.”

They also instituted a 4 p.m. happy hour.

“We decided we were very elegant so we’d have a gin and tonic on the porch,” June added. “We always had maraschino cherries and had a gin and tonic every afternoon.”

Only, gin was hard to come by in the valley at that time. The Squamish liquor store—the nearest such establishment—had to special order it in for them.

When it arrived, the “train man” would pick it up for them, slip it into a shoebox and deliver it with a coy, “Here’s the shoes you ordered.”

“Very discreet,” June said. “I thought that was wonderful.”

While they might have kept their cocktail hour low-key, the loggers who would come into town on break from their camps did not.

“The big time up here was July 1,” June remembered. “It was pretty wild. It was mostly loggers around here and they had the day off so they would drink all day and be going to work on the train … We tried to avoid that because they’d get out of hand. They were nice, but when they were drinking, they’d get out of hand. We kept a very select group around. We didn’t have [just] anybody visiting us.”

However, a Whistler Museum blog post recounts a story Florence remembered about pulling a prank on the seasonal workers at the nearby forestry cabin.

She and her visiting teacher friend, Julie, were out for a walk when Julie accidentally killed a grouse while tossing rocks down the path. Ever the biology teacher, Julie decided to skin the bird and the pair stuffed it.

They took the stuffed bird into the cabin and hung it above the door so that it would fall in the face of whoever entered next.

Not satisfied with just flying poultry, they also took the cabin’s cutlery and shoved it in a sleeping bag they found.

Unfortunately for those forestry workers, their boss had been up from Vancouver that day and, when his departure was delayed until the next morning, he wound up the recipient of both the bird-in-the-face prank and the sleeping bag full of forks.

“Of course, all the forestry kids knew who it had been, but they wouldn’t say,” Florence said in the post.

Those kinds of pranks were a staple at Witsend.

The one that stuck in June’s memory came at the hands of Kelly.

Sometimes, if there were horses leftover at Rainbow Lodge that guests weren’t using, the Witsenders were allowed to ride them.

“Kelly was always such a demure and sweet little thing. There were only four horses [one day] and she said, ‘I’ll stay home,’” June recalled. “We thought that was nice of her.”

When they returned from their ride, “Kelly looked like she was going to burst. Her eyes were sparkling and she looked full of something. We said, ‘What are you up to?’ She said, ‘Oh, nothing.’”

That night, when they got ready for bed, they discovered how Kelly had spent her afternoon alone: sewing up all their pyjamas an inch so no one could get into them.

Then they tried to climb into bed.

She had “apple-pied the beds,” folding the sheets back on themselves halfway down, making it impossible to get in. Finally, the cherry on top of that apple pie: she filled the bottom of the bed with pop bottle caps.

“It’s funny because my mom was probably one of the quieter ones, but she was wickedly funny sometimes,” Carol says. “She had such a sense of humour. But it was that good old-fashioned fun. I don’t think they were beneath a good party. I think they had a good time.”

For Pat, who, along with Denis, is one of the only people still alive who experienced Witsend first-hand, her most vivid memory of those days is the music.

“The sing-alongs were the best thing going,” she remembers. “We’d sing all the old songs. Someone would have a banjo, and Jacquie was good at the ukulele … I’d play the banjo.”

Carol, who grew up in Whistler, remembers a particularly musical moment when the group got together at Jacquie’s Alta Lake Road house for Witsend’s 20th anniversary.

A teen at the time, she was walking down the road with a friend when she heard singing punctuated by gales of laughter coming from a porch.

“My mom was sitting at the barbecue, playing it like a piano and they were all gathered around it singing away,” she recalls with a laugh. “They were just goofing around. It was the funniest thing.”

The end of Witsend

The party lasted for 10 years.

Witsend succumbed to the fire in November 1965, just before Whistler Mountain opened.

By that time, Kelly, who had married Dick in 1958 and was over at the Cypress Lodge, had sold her shares. Then, in 1964, Jacquie sold her shares to buy her home nearby.

And after the fire, June sold, too.

That left Florence and Betty as owners of each of the lots that made up the property.

“We were still welcomed; we weren’t abandoned,” June said with a laugh. “That was the end of the Witsend group, but we kept together. We saw each other frequently.”

They visited each other when they could and endeavoured to get together to mark milestone anniversaries of Witsend.

“I miss all of them,” said June, who passed away in 2018. “I’m the last Witsender. I do miss those girls because we used to have so much fun.”

While they left a mark on Whistler history, the valley, in turn, shaped the rest of their lives too.

“I think they knew how lucky they were,” Carol says. “I really do. I think they always did. I know my mom certainly did and Florence certainly did. That’s why they stayed so long. From my perspective, I think they built something that they really wanted and really mattered to them. And I do feel like they also gave back a lot. I think they were a valued group that would contribute to the community.”