Libraries existed in some form for thousands of years before the establishment of The Great Library of Alexandria—but none were nearly as ambitious.

Built by the Ptolemaic Kingdom sometime between 285 and 246 BC, The Great Library was founded with the aim of amassing and preserving no less than the entirety of the world's knowledge (although showcasing Egypt's immense wealth and power was clearly a welcome side effect). Some historians estimate that, at its peak, the sprawling marble and stone complex housed up to 400,000 papyrus scrolls, filling the stacks with works in mathematics, physics, astronomy, natural sciences and philosophy. Believed to be the first "universal library," it was, by virtually any measure, the world's single largest repository of information for roughly 300 years.

You can draw a direct throughline from Alexandria's library to the modern library of today. For the Ptolemies, it coincided with a broadening worldview and unyielding thirst for knowledge. It was, to say the least, a project of outsized vision—but then libraries have always been an aspirational endeavour. The library not only holds up a mirror to the society it serves, it pulls us further towards the society we want to become.

Far from the rigid, dusty institution it is sometimes portrayed as in popular culture, the modern library is constantly adapting to the needs of its community. In North America, libraries have been undergoing a foundational technological and cultural shift, moving away from the gatekeeping role of years past to a more dynamic, inclusive approach.

Take the Whistler Public Library (WPL), in many ways a microcosm of this evolution: Prior to its extensive 2014 strategic plan, its slogan was "Gateway to Knowledge." Today, its mission is to "Inspire Wonder."

"[In the past] we were gatekeepers of the public trust, as if these things are ours, when, really, everything in here and everything this place is belongs to this community," says library director Elizabeth Tracy.

The great equalizer

There are a number of factors contributing to the belief, at least in some circles, that libraries are gradually going the way of the dodo bird. Whether the explosion of e-readers and audiobooks, a sweeping decline in public funding, or a long-entrenched view of the library as an archaic institution resistant to change, a refrain of the past few years has been that libraries are steadily moving closer to irrelevance.

But in a time of social and cultural upheaval, the unifying power of libraries is more essential than ever, says Nadine White, public services librarian with WPL.

"I think the library is the great equalizer, and that's really needed right now. So, in fact, our importance has increased, not decreased," she says.

University of California, Irvine philosophy of science professors Cailin O'Connor and James Weatherall have dubbed the current fractured political era as "The Age of Misinformation," a time when social factors, rather than individual psychology, are the biggest contributor to the spread and persistence of false beliefs. What were once collectively agreed upon facts have turned into battle lines drawn in the sand. It seems even truth itself is constantly, violently up for debate. In this swirl of "alternative facts," the library can be a port in the storm.

"It's a social nexus," says Susan Parker, university librarian for UBC. "Everyone else has an end game, a message they're trying to deliver. Our message is basically that we have information and we want to make sure you have access to it, and we have experts. Whether it's a public library, an academic library, or even a school library, we have people who are trained to help you find the newest information, people who are trained to help you steer clear of fake news, trying to identify what's real and not real, trying to validate the sources of information that you have as trustworthy. All of those things would be lost without libraries.

"There's some human dignity in having a place like that available."

Over at WPL, the library regularly welcomes a mosaic of patrons through its doors, be they long-time locals, tourists in town for a weekend, a new immigrant beefing up their English skills or the underhoused catching a few Zs by the glow of the fireplace.

In a community that welcomes the world, WPL is one of the only places where Whistler's diverse cross-section of residents, seasonals and visitors can interact.

"The library plays an important role in being one of those few spaces where people from all walks of life do share space together," says Kayley O'Brien, WPL's youth services librarian. "There aren't a lot of places where that happens, so it's a place where we can generate empathy for one another and realize we are all people, we want to do the same things, and that's OK."

The signs of WPL's inclusive approach can not only be found in its recent physical renovations, but in the radical transformation to its service culture. One of the more significant shifts was the creation of a public services department, which merged the library's circulation and reference teams, emboldening staff to "have more ownership over their work," White says. That also coincided with a new, behind-the-scenes department called materials management. It was all part of WPL's push towards a "barrier-free" service culture.

"There's this traditional divide between a reference desk and a circulation desk," adds White. "You're basically requiring that the patron go all around the library trying to get done what they need to get done. That isn't what we stand for."

With the addition of its 360-degree service kiosks, coupled with new self-check stations, patrons can now take advantage of a single point of service. No longer are library users divided, quite literally, by a large, imposing desk. In fact, staff are encouraged to leave their kiosk and find patrons where they're at.

"We have a phrase called 'Point with your feet, not your fingers,'" White says. "We're no longer the librarians that sit at the desk and expect you to come to us—and no shushing!"

Much of the change at WPL can be linked back to Tracy, hired as library director in 2012. Coming from Wilkinson Public Library in Telluride, Colo., she understood the all-encompassing role a resort library should play.

"Coming from working in a library that was in a resort community influenced how I saw the function of a library," Tracy says. "I thought, in a resort community, you get to meet that highest aspiration of what a library can do, because you are in a position to serve everyone."

("Serving everyone" is a philosophy that's actually baked into B.C's network of libraries: Not everyone is aware—I sure wasn't—that anyone with a B.C. library card can borrow or drop off books at any other branch in the province.)

When the Whistler Chamber of Commerce revamped its resort-wide customer service program, Whistler Experience, Tracy says WPL staff underwent the training, which happened to come at a time when the library was already rethinking its service approach.

"We hitched ourselves to that wagon because it gave us a common vernacular across all the organizations in the community to use, and [showed] that we were part of this larger framework providing excellent service to the community," Tracy adds.

The relationship has since evolved to the point where Mark Colgate, a service management researcher with the University of Victoria, who was also instrumental in developing the chamber's revamped Whistler Experience program, recently used WPL as a case study.

Colgate identified several ways the service training ultimately benefitted the workplace culture at WPL, including incorporating the learnings into everyday language among staff, an emphasis on "coaching and the guidance on how to build a coaching culture," as well as regularly tracking Secret Shopper scores. WPL has now been recognized through the chamber's Secret Shopper program multiple times.

"Our philosophy was looking at how many times we said no, and turning that into a yes," explains White of the shift. "That really had a big impact on the community and made it much easier to fundraise, and then have people support us make those physical changes that people started to see."

From the shack to the palace

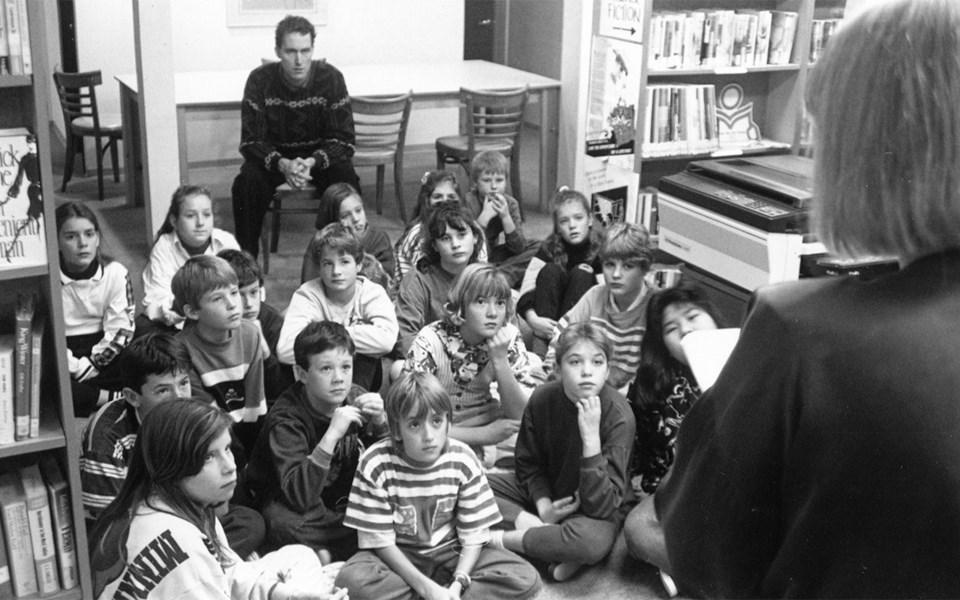

In 1994, the WPL board began the search for the library's new facility, eventually moving from its original location in the municipal hall basement to the old Canada Post trailer that would be moved to Main Street.

Ralph Forsyth, Whistler council's appointee to the library board, and who has been involved with WPL for years, remembers the cozy, ramshackle confines of WPL's previous location.

"It was creaky, it was drafty, but it was home," he says.

The community continued to grow as it inched closer to the 2010 Olympics, and the need for a larger library was apparent. The converted trailer, always intended as a temporary home, had outlived its usefulness.

In January 2008, WPL officially opened the doors to its current permanent location, an airy, 12,000-square-foot, LEED-certified facility that is arguably one of Whistler's most beautifully designed—and beloved—buildings.

But the community wasn't immediately receptive to the WPL's new base. The building's steep price tag, originally pegged at about $7 million, escalated to more than $11 million when all was said and done, a consequence of B.C.'s tight construction market.

"It's hard to believe now, but it was a controversial project at the time," Forsyth recalls.

The move "from the shack to the palace," as White jokingly describes it, and the controversy around it, meant library staff were that much more devoted to giving the community what it wanted.

"It was hard to live through, to work in a space that had that negative press about it, because the people who used it, loved it," White notes. "But I think it did force us to be very community driven, to really be able to show how we were using community input in order to build the collection or create our programs. In the end, it was really beneficial, actually."

Input from patrons proved invaluable in the long run. WPL has imbued its service approach with the flexibility to adapt to a community that is no stranger to change.

"The community does make it easy, because if you're willing to listen, adapt and change, they tell you," says Tracy. "They tell us all the time how they want to use us, just by their behaviour or what they actually say or write to us."

A 2017 vision survey of 480 patrons led to the drafting of WPL's latest strategic plan, but also served as the basis for a space-needs assessment. The survey focused on "two things we felt to be major assets at the library right now," Tracy said: Space and technology.

The library's original design firm, HCMA Architecture, won the bid for the library's interior renovation. Among the major changes were the addition of tutor space, quiet booths and relocating the teen area, which freed up reading space near the fireplace. The renovation has created a more modern, open and inviting environment, with future plans to add glassed-in meeting rooms, as well as the Wonder Lab, a technology hub that will replace the current computer lab.

"As an organization with limited resources, whatever changes we make, whatever we decided to do has to have a certain level of timelessness to it. It also has to transcend the test of time in terms of how the library is going to change—but it also needs to be prudent," Tracy says. "We can't blow the place up, as fun as that would be. This is one of the most beautiful buildings in Whistler and we're really proud of that, we're proud to work here, so the recommendations [HDMA] brought back really honoured the feedback that we got. But, also, we're not too ... disrespectful of the things that are great about the space already."

More than just books

The irony of the view of libraries as outdated institutions is that libraries, both public and academic, are increasingly becoming hubs for new technologies. More importantly, they offer access to technology that would otherwise be out of reach for many.

Among the features slated for WPL's Wonder Lab, expected to open late next year or in early 2021, are a large-format printer, ideal for backcountry maps; high-end photo and video editing software; a sound production pod; a green screen; and, if all goes according to plan, a vending machine that, instead of sugary soft drinks, will lend out laptops for patrons to use anywhere in the building.

"These are really cool but not incredibly expensive things, things that might just be out of reach to the average person," Tracy explains. "You can imagine, in today's world, how students could be thrust in a different direction by having that initial contact with technology like that. Or for seniors, it's the great equalizer in a world that's changing so much."

In 2014, the Edmonton Public Library opened one of Canada's first "makerspaces," billed as "a completely public creative and collaborative environment where ideas are shared, expanded and brought to life." In start-up-friendly Edmonton, suddenly anyone with a library card and an idea had access to a 3D printer, high-performance computers and design software, a recording studio, a vinyl cutter, robotics kits, and more. The space even allows users to self-publish books in mere minutes on an Espresso Book Machine, or, in the ideal enmeshment of old and new, convert outdated media into modern formats using a digital conversion station.

At academic libraries, the technology available tends to be even more specialized—not to mention, cutting-edge. At the University of British Columbia, the library offers an exhaustive archive of electronic material, primarily made up of e-books and scholarly journals, that is constantly being updated. It offers access to a wide range of technological tools for use, like Raspberry Pi, a credit-card sized Linux machine for people who want to learn coding. At UBC's Emerging Media Lab, students develop projects in augmented and virtual reality.

"It's very cool," says Parker, UBC's library director. "I was just in there taking a tour and I was using the program that a faculty member developed where you learn how to conduct an orchestra. You use a virtual wand and it tracks all your strokes so you can see where you need to improve. I also just took a virtual walk through Stanley Park through a tool that was created.

"The library offers some really big technology spaces," she adds. "A lot of scholars are working in creating things in the digital realm and they need a place to do the creation, but also to display it."

UBC has also gone to great lengths to digitize large swaths of material, called "open collections," that are available for anyone—UBC student or not—to peruse online. Much of that material focuses on the history of B.C., and especially Vancouver, and includes a treasure trove of photographs and other source material.

Parker believes it's this, the management of new online and digital collections, that will be a major focus for libraries in the future.

"Libraries are still going to stick to their traditional role, of archiving information and making sure it's available," she says. "A lot of this digital information that we're talking about, it needs to be preserved, and libraries have thought about that in significant ways. Especially unique information that we may have created, like our online open collections, like collections of research data that are generated through a university—how do we preserve that for the future?

"I think that's probably the biggest thing: The unique collections that we have, of rare books and specially collected manuscripts, we'll be the stewards of all those. Pretty soon those things will come in a digital form, not as manuscripts, and we'll need expertise to preserve that and ensure that, over generations, our staff will still be able to read it and those technical skills will still be there to manage it."

A radical approach to Indigenizing a library

Since it opened in 1993, the Xwi7xwa Library has remained the only Indigenous branch of an academic library in Canada.

Housed at UBC, Xwi7xwa—meaning "echo" in the Squamish language—takes an Indigenous approach to collections, research and programming and is often looked at as a leader in Indigenous academic librarianship both in the province and beyond.

"As the only Indigenous academic branch library in Canada, its very existence is non-standard," says Adolfo Tarango, acting head of the library. "We've created a special collection that's curated to reflect Indigenous perspectives and to highlight those Indigenous perspectives."

Most academic research libraries in North America use the Library of Congress Classification System, which arranges materials and subjects alphabetically "without any real sense of how these subcategories relate to each other," Tarango explains.

"That is a very Western perspective on how you organize knowledge and present it to users."

The Xwi7xwa Library instead utilizes the Brian Deer Classification System, which arranges materials through more of an Indigenous lens: geographically. "So the materials from British Columbia on any particular topic are adjacent to the materials from Alberta, etc. so that there is a geographical context provided and that's visible on the shelf as people are accessing that material," Tarango notes. "That's just a very different way of physically organizing the materials."

Xwi7xwa also makes use of the First Nations House of Learning Thesaurus, which "allows us to use terms that are relevant to Indigenous communities and terms that are more appropriate for certain concepts."

Particularly for historically under- or misrepresented communities, it's important to have space dedicated to preserving and collecting its inherent culture in language that the community can see itself in.

"I think that libraries are ideally situated to do this because, even though we may not have done it in the past, or we did it in a way that was not perhaps the way we should have been doing it, we have an opportunity to work with those communities to preserve information in the way they see it needed to be preserved, and to manage it according to the ways in which they manage it," Parker says of libraries' role in preserving collections from marginalized groups.

That means not all materials at the library are available to just anyone. The respective Indigenous communities themselves dictate how their information is collected and disseminated.

"As we look at those materials, we want to make sure we're using them appropriately, and doing research in terms of, 'OK, what are the actual cultural and intellectual property rights involved here?'" Tarango says. "We might have a homemade video of a ceremonial dance, and we, first of all, do the research to identify what it is. Then, once identifying it, we come out to the community and say, 'We have this. Is it appropriate for us to have this?' And if it's not, we then take steps to reconcile that, and that might mean returning the material to the First Nation, or they might say, 'Oh, no, it's perfectly OK for you guys to have it, but you need to have certain restrictions, like only elders can view it, or only members of the tribe.'"

Xwi7xwa also plays a role in cataloguing the largely oral traditions of many B.C. Indigenous groups, through audio tapes or other media, which in turn helps keep those languages from disappearing—some of which, including the Lil'wat Nation's native tongue, Ucwalmícwts, are down to only a handful of fluent speakers.

"We are, in some ways, limited because we are a library and not a linguistic department," says Tarango. "But clearly, in terms of us collecting materials in the native languages—so if something is done in Musqueam, Coast Salish or whatever—we are definitely interested in collecting those materials and making them a part of our collections, so that a native speaker could potentially come to our library and find the materials in their native languages."

Along with the important cultural and historical role Xwi7xwa plays, having a dedicated Aboriginal library on a campus of 63,000 is a bellwether for the school's and surrounding community's Indigenous population.

"In Canada, and in North America in particular, I think there is a need for our type of institution, where the focus is very clearly about Indigenous culture and knowledge," Tarango says. "I think we serve a really special role at UBC in creating another space on campus that's very welcoming of Indigenous community, and, of course, supporting the mission of the university in perpetuating the growth of Indigenous knowledge. We want to serve the community."

Far from obsolete

Probably the mostly widely believed theory behind the destruction of The Great Library of Alexandria is that it burned down in 48 BC when the city caught fire during Julius Ceasar's Civil War. Historians say it's more likely the library was damaged in a number of different fires over the course of centuries, part of a long decline in funding and support.

It's hard to imagine the library of today suffering a similar fate. While the ways in which a library operates, and the materials it provides, have changed, the core of what a library does has remained virtually the same.

"It's an extension of what libraries have always done, because libraries have always been about making information available to people with the fewest possible hurdles," says Parker. "The thing that has changed isn't libraries, but libraries are now one of the few places where you can go and not be asked to spend money on a purchase to sit and use the facility."

One of the last great refuges for people of all colour, creed and background, the library will always serve a purpose as long as the innate human desire for progress, to improve our lot in life, lives within us. There is no other place where, all under a single roof, our imagination can be sparked, our preconceived notions can be challenged, and our collective sense of humanity can be continuously reinvigorated. It's difficult—and depressing—to imagine a society without libraries.

As journalist and author Caitlin Moran put it, a good library is "a cross between an emergency exit, a life-raft and a festival. They are cathedrals of the mind; hospitals of the soul; theme parks of the imagination. On a cold, rainy island, they are the only sheltered public spaces where you are not a consumer, but a citizen instead."