It feels poetic—if not a bit on the nose—that Whistler’s largest and longest-running arts organization can trace its origins to a dark and stormy night during the winter of 1982.

“It really was dark and stormy, I swear,” recalls Glenda Bartosh, Pique columnist and founder of the Whistler Arts Council, which would eventually rebrand as Arts Whistler. “It was a dull, rainy, horrible night in January, and I thought, ‘What if I started a group like an arts council, that people could join, and make it bigger than the sum of its parts? For the people by the people.’”

Growing up in Edmonton, Bartosh was exposed to the arts from an early age. After winning an art contest in Grade 1, she was enrolled in classes at the Edmonton Art Gallery, and in high school, held aspirations of becoming a commercial artist herself. In her adult years, she lived at various points in New York, San Diego and finally Vancouver, eagerly taking in each city’s cultural offerings.

“I’m an old hippie and in the ’70s, all those creative forms of expression were huge in culture and a really big part of my life,” she says.

So, by the time Bartosh landed in Whistler in the early ’80s, she yearned for more of the arts and culture that had been such an important part of her life.

“I came to Whistler and—have you ever heard the term ‘hippie jocks?’” she asks. “I was never a jock. Just think of living in Whistler at that time: skiing was so big, there was no snowboarding yet, and I was never athletic. So that hole for me was art and the town was very sports-oriented.”

Determined to fill that void, Bartosh happened to have just the right megaphone to amplify her community callout. Then the owner, publisher and editor of the Whistler Question, Bartosh leveraged the resort’s original paper of record to help get the word out about launching a new arts council.

“I had the Whistler Question and I could use it. I didn’t have to bounce the idea off an editor,” she explains. “I knew I could leverage the Question, the power of the press, and get people to come out and get interested in the events. I didn’t ask anyone, I didn’t bounce the idea off of anyone. I just thought of it one night.”

Bartosh’s shoot-first, ask-questions-later approach was indicative of the community at the time, then a plucky ski-bum enclave of only a few hundred year-round residents, and it set the tone for the Whistler Arts Council’s next two decades.

After placing an ad in the paper, Bartosh was pleasantly surprised when around 15 people turned up to a Delta conference room for the council’s inaugural meeting. Despite Whistler’s apparent lack of culture—or perhaps because of it—it became clear locals were hungry for more. Attendance boomed, business owners bent over backwards to sponsor events, restaurateurs copped visiting performers free meals, and hotels offered space for meetings or exhibitions free of charge.

“There was never any doubt in our minds that it would work. We knew we were on the right track and we were confident it would spark people,” Bartosh says. “And look at the businesses, really supportive; the hotels, really supportive. The restaurants, gift shops, everyone.”

That enthusiasm extended to the nascent council’s first board of directors, too. Without any staff or major funding to speak of, the board of those days took on any number of responsibilities, whether it was conceptualizing and organizing events, serving as production crew or manning the ticket stand. And if they had a vision for a new program or event, chances were good it would bear fruit.

“What was exciting for everyone on the board, if you had an idea you could probably run with it and make it happen,” says Joan Richoz, who joined the council in 1983 and has since filled virtually every executive position on the board, from secretary to treasurer to chair. (Richoz’s commitment to Arts Whistler runs so deep that she served on the board for 32 years straight, until 2015, when she took a year off after the organization changed its bylaws to add term limits. She is now on another break following her latest six-year term.)

One of those early concepts the council ran with at full speed was the Whistler Children’s Festival, launched in 1983 and today is Whistler’s longest-running event. The idea was hatched largely because the community’s small elementary school, Myrtle Philip Community School, at the time didn’t offer a fine arts program. Margaret Long, a teacher herself, envisioned an immersive festival that was arts-based, rather than performance-based.

“It just all coalesced. The town was ripe for it,” Bartosh says. “[Long] had Heather, her daughter, and she had been going to the children’s festival in Vancouver, but there was a big problem with the children’s festival in Vancouver: the kids didn’t do anything. They just sat passively and watched. Margaret would make sure our children’s arts festival allowed kids to actually do things, like paint or make art or dance. The idea was participation, not just watching.”

The resulting festival, chock-a-block with immersive workshops and live demos, alongside a handful of stage shows, reflected the arts council that produced it: hands-on, participatory, engaging.

It’s not hard to see the throughline from the children’s festival of 40 years ago to the slate of programming Arts Whistler offers today. Several of the organization’s anchor programs—like The Teeny Tiny Art Show, which asks experienced artists and eager amateurs alike to submit a small-but-mighty work on a three-by-three-inch canvas; or the Anonymous Art Show, a major fundraiser and frenzied live auction of works by local artists of all stripes whose names aren’t revealed until a piece is sold—are designed to encourage participation and break down the traditional stigma attached to the stodgier segments of the art world, aligning with Bartosh’s original vision for an arts council that was democratic, inclusive and community-led.

“That’s something we recognize we can do: inviting more people from the community to be part of the process, like the Teeny Tiny Show. It’s the gateway drug for artists. They do Teeny Tiny and think, ‘How badly could a three-by-three-inch piece go? It’s small. I can do this.’ They feel empowered and then maybe that work sells for a few bucks so they decide they’re going to do the Anonymous Show. Then we have an open call a few months later for something more sophisticated and some of those artists throw their hat in,” says Mo Douglas, Arts Whistler’s executive director, who took over the role from Doti Niedermayer in 2016.

Building on the standard set by the children’s festival, as the Whistler Arts Council matured through the ’80s and into the ’90s, its programming evolved with it, continuing the organization’s trend of punching above its weight, even with stretched resources. A prime example is the performance series organized by Richoz and Tamsin Miller, which brought a steady lineup of burgeoning bands to the resort, many of which would go on to greater fame in the industry.

“When I look back at the names of the performers we had, a lot of them are bigger names now, which is the whole point of touring artists,” Richoz says. “It was so much fun, getting to meet all these performers from across the province and the country. Sometimes they’d come over to our house for dinner. We got things done pretty quickly back in those days.”

But with that prolific output came burnout. There was, after so long, only so much a completely volunteer-led group could do.

“It got to the point where people were getting really burned out,” Richoz says. “It’s a lot to put on these events, with very little funding. We didn’t have the municipal funding that there is now. It was BC Arts Council grants, Touring Council grants. It was getting hard.”

‘We realized we had to evolve’

By the turn of the millennium, as Whistler sat at a crossroads between its past as a hardscrabble ski-bum haven and its future as a global tourism behemoth, a sentiment that seemed to prevail across the wider community became apparent at Arts Whistler: it was time to level up.

“We realized we had to evolve,” Richoz says. “After 20 years of being totally volunteer run, we needed to get more support from the municipality.”

It was around that time the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) commissioned an arts plan that included several recommendations, two of which would entirely overhaul Arts Whistler’s organizational structure. One was to add an executive director, the other was to add members from Whistler’s resort stakeholders to the board.

Niedermayer, Arts Whistler’s first executive director, still remembers the lengthy interview process she went through before being hired in 2002. Living in Nelson at the time, she would make the long drive down for a series of interviews she did with as many as eight or nine people at a time. (She requested they cover her gas money, to no avail: “I said to them later, ‘I should’ve known then you were a bunch of cheap buggers,’” Niedermayer recalls with a laugh.)

“Talk about intimidating. What the hell? I’ve never been interviewed by nine people,” she says. “But they were so keen to make the right decision that they had a member of the RMOW. Kirby Brown was there from Whistler Blackcomb; he was the employee experience manager at the time. A staff member from Tourism Whistler was there. Board members from Arts Whistler. It was ridiculous how many people were in this friggin’ interview.”

Even still, living as far away as Nelson, Niedermayer knew she shouldn’t rush into anything. “I’m not upending my life to come here if it’s going to be a big mistake. For me, it was as much an interview of them as it was of me,” she says.

Then, just like it did for Bartosh when she was first forming the council, things seemed to magically fall into place. Niedermayer already knew she wanted to be closer to her aging mother, who lived in Vancouver, and Whistler checked that box. Then, when she was looking for an affordable place to live, Richoz connected her with a contractor who had just finished installing a suite at a home in Alpine, and he put her in touch with the landlord.

“It was one of those situations where it was meant to be,” Niedermayer remembers. “You look at it and you go, ‘Everything happened fast and it was virtually seamless.’ It was just a sign that it was the right decision.”

That right decision was reiterated again as Niedermayer settled into her new job and learned more about what the organization had achieved to that point.

“I walked into this organization expecting quite a mess, or things to be really Mickey Mouse, because I knew I was the first full-time professional there,” she says.

Instead, she found a professional slate of programming with a dedicated following, funded largely through grant applications, and a tireless board eager to take the organization forward into its next iteration.

“I remember saying to Joan, ‘You’ve written really good grant applications. You’ve really built a great program. We have a following, we have an audience, we have respect from the funders. You guys have brought professional performers to town. This is awesome,’” says Niedermayer.

“There were a couple of programs they had built and created that I inherited that really gave me a solid foundation to start from. I was actually really impressed by that. It was really great to come into that and build new programs.”

The next step for the council was hiring paid staff. As the organization grew in scope and acquired more municipal funding, it went from a one-woman show with just Niedermayer at the helm, to first adding an assistant, then someone in marketing, then admin staff.

“As we went forward and took on more programs and got more money, I was able to hire more and more people,” she says. “We went from a staff of one to a staff of 20 when I left [in 2015].”

The additional manpower (or womanpower, considering the predominant makeup of the staff, a trend that continues today at Arts Whistler) couldn’t have come at a better time. In July 2003, less than a year after Niedermayer came onboard, Whistler was named as a 2010 Winter Olympic host, a golden opportunity to showcase the community—and more importantly, for Arts Whistler’s purposes, the community’s inherent culture—to the wider world.

In short order, Niedermayer was contacted by a former colleague who was charged with helping organize the Games’ cultural programming. “He said, ‘Look, I really think the arts council needs to be a part of this, because you are the arts for Whistler and we want to work with you.’ He was very much a community guy, and I said, ‘Sure, bring it on,’” she remembers. “That propelled the arts to move really fast in getting ready for the Games that were coming.”

In honour of being awarded the Winter Games, Whistler launched Celebration 2010, an annual slate of live performances meant to herald the coming Olympics in the years leading up to the Games, as well as hosting the Cultural Olympiad in 2008 and ’09, a watershed moment for the resort’s arts scene. Featuring a diverse array of more than 300 performances and 10 exhibitions across the Sea to Sky and Lower Mainland, the Olympiad was a mixture of Canadian, B.C. and local talent, the latter also working behind the scenes wherever possible.

“We spent all of our time and energy during the Cultural Olympiad hiring and giving exposure to local artists,” Niedermayer says.

For many local artists, it offered the chance to both refine and promote their practice, not always an easy feat for creative types, doubly so in a town where the arts have always played second or even third fiddle to sports and nature. The historic moment also pushed local creatives to take themselves and their work seriously, the rising Olympic tide lifting all boats.

“That’s when we started doing live painting, and taking people who’ve never painted in front of a crowd before, like [late, great local artist] Chili Thom or whoever, and going, ‘We’re going to put you on the street, and now you’re going to have to answer questions and engage with the public and you have to show up on time,’’’ Neidermayer says. “Are you a professional artist or aren’t you? Are you gonna show up and do your job or are you just going to do it for fun?”

The years leading up to the Games would come with another sea-change for Arts Whistler: solidifying its home base at the Maury Young Arts Centre (then Millennium Place), with the RMOW, which owns the facility, eventually tapping the organization to manage the building and take care of venue bookings.

“I think it gave us opportunity because we were freely able to program the space as much as we wanted and we were able to create new relationships, new partnerships and new alliances with commercial and community renters,” Niedermayer says. “We were now able to say, ‘OK, arts community, we’re able to give you the space at an affordable rate,’ so now we’re creating better connections with the rest of the arts community.”

With the management of Maury Young came a handful of new dedicated staff members, as well as a closer working relationship with the RMOW.

The move also speaks to the tricky balancing act Arts Whistler still has to strike today, between its core mandate of supporting and furthering the local arts and its goal of putting butts in seats at the Maury Young theatre through big-ticket acts from outside of the resort.

“There is a demand from the community for outside performances and work. Then there is the demand by local artists to be given an opportunity to be showcased and recognized and to further their professional career. It is a balancing act and it is difficult and complicated,” says Niedermayer. “I think it’s any organization’s challenge when they’re a local community organization trying to fill those two shoes. You kind of have your eye on both.”

Weaving the tapestry

With the momentum of the Olympics behind it, the RMOW commissioned a report in 2011 that examined Whistler’s potential as a cultural tourism destination. Authored by Steven Thorne, the big takeaway from the report, entitled “A Tapestry of Place,” was that visitors were looking for “authentic, place-based experiences” when coming to a new destination. While it doesn’t sound like much of a revelation today, a decade ago, Niedermayer says the report—spearheaded by the RMOW’s then manager of strategic partnerships, John Rae, who has long been one of municipal hall’s most fervent champions of the local arts—was done in part to convince the powers that be that Whistler’s cultural offerings were significant and marketable to guests.

“The reason we were doing that cultural tourism strategy was for exactly that reason: to confirm to the community and the decision-makers that culture is important to selling the resort,” she adds. “That’s why we actually had to pay to commission a report to say what we already knew. It’s only when it’s official that everybody believes it’s true. That’s just the nature of the way people do business.”

Uphill battle

To say that Whistler has come leaps and bounds in its recognition of the arts would be an understatement. “The difference between 2002 and 2022 is huge in terms of the amount of acceptance of the arts community that Whistler has,” Niedermayer muses.

Today, arts and culture are simply another spoke in the tourism wheel, and marketed as such, whether through Tourism Whistler, the RMOW or Arts Whistler. But as any local artist or performer can tell you, the fight for recognition in an unapologetic sports town remains an uphill battle.

“I would love to see it be a bigger component,” Richoz says of the arts here. “For some people, it’s not so important in their lives. Not everyone is as passionate about the value of arts and culture as we are. For years and years, I thought, ‘We’ve got to have a day without art and I bet people would be really surprised that they wouldn’t be able to do anything.’

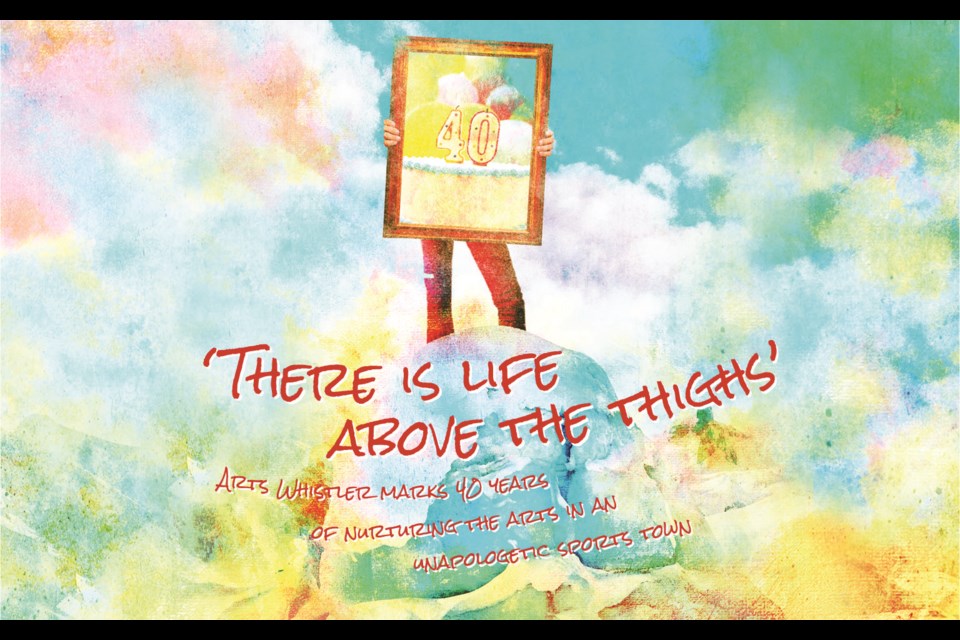

“As Tamsin Miller used to say, in Whistler, there is life above the thighs. Because everything here is focused on the thighs, on sports, on skiing, on snowboarding, on biking. But there’s more than that here.”

Part of the uphill battle is the transience inherent to Whistler; with each annual influx of new faces comes a fresh batch of residents, many of whom either put their creative pursuits to the wayside while they’re here or are simply unaware of the artistic opportunities already available to them.

“It’s so fun to have names pop up that we’ve never heard of before but they’re doing great stuff. I think it speaks to the transience,” Douglas says. “We are now in a better position, because there’s a stronger appreciation and awareness of what Arts Whistler does, to grab those transient people who might only be here for a season and do want art to be part of their life while they’re here.”

Remarkably, at least considering how plugged in our world is today, it was actually a print publication—just like the Question before it—that helped move the needle on public awareness of the arts in Whistler, according to Douglas. In 2016, Arts Whistler received a $489,000 Canadian Heritage grant to grow its online and print marketing. That led to a revamped website that continues to serve as a one-stop shop for all cultural events and activities across the Sea to Sky—including programming not produced by Arts Whistler—as well as the seasonal print brochure, Arts Scene.

“The physical presence of it was very important for Whistler and the Sea to Sky community to understand that arts and culture is really vibrant once you could see it as the sum of all its parts,” Douglas says.

That coupled with an effort already well underway at Arts Whistler at the time to serve as the connective tissue between the resort’s various arts organizations and venues, exemplified through the municipality’s Cultural Connector, a scenic pathway that counts six cultural institutions along its route: Maury Young, the library, Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre, Whistler Museum, Lost Lake PassivHaus and the Audain Art Museum, with notable waypoints and information on the resort’s cultural evolution featured throughout.

Sometimes, though, it’s not just the tourists who need convincing. Sometimes it’s the artists themselves who need to be reminded they have something valuable to share with the world, and that’s where Arts Whistler can and has played a crucial role, arguably even more so in the pandemic, when performers saw their live gigs dry up and wither in an instant. Take the Hear and Now Festival, usually a slate of in-person live concerts by local bands, that was transformed to a series of slick video performances recorded onstage at Maury Young; or the related Creative Catalyst project, which invited a handful of Sea to Sky musicians to sharpen their skills on the creative, production and promotional fronts.

“When you look at the musicians seeing themselves back through the Hear and Now video project or what we did with the Creative Catalyst, I think there were huge learnings with musicians,” Douglas says. “It’s about being able to both provide opportunities to let them shine but also opportunities where they can see themselves and see their own opportunities to grow. It’s huge.”

And yet, for all the progress that’s been made, there is of course still room for the arts to become a bigger component of Whistler life. So what does the future hold for Whistler’s largest arts organization?

“I think we’re on that same trajectory to continue to raise awareness of Whistler’s authentic, locally based cultural scene. We would really like over the next, say, five years, to have a higher awareness among people coming to the resort, that they’re seeking out these experiences as opposed to just stumbling upon them,” Douglas says. “The locals have that experience all the time, but the visitors take that away and it becomes a unique differentiator for us as well.”