Every year, hundreds of people are hired across British Columbia to fight wildfires in the peak of summer’s sweltering heat. Months spent digging trenches, attacking the fires with helicopters, bombers and hoses.

It’s a vital job that is becoming even more critical as British Columbia continues to face more frequent and severe wildfires due to the worsening effects of climate change.

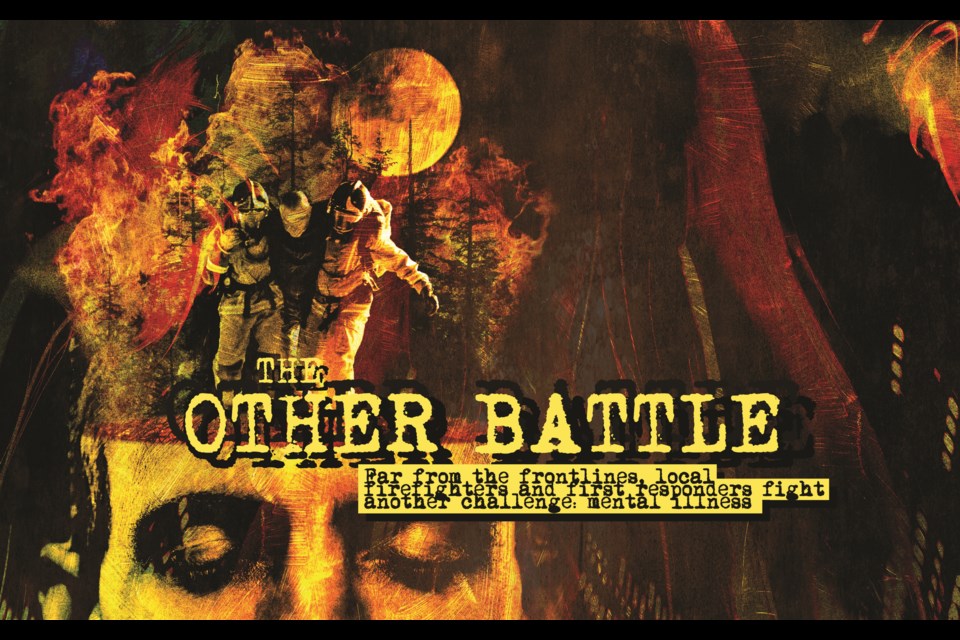

Yet, in some ways, battling the blaze is the easy part of the job. In recent years, there has been a broader understanding of another, less visible battle first responders such as firefighters, paramedics and law enforcement also must fight: the heavy mental and emotional toll that can come with a career on the frontlines.

An estimated 70,000-plus first responders in Canada have experienced PTSD in their lifetimes. Canadian first responders experience PTSD and critical incident stress at double the rate of the general population, which can lead to increased work absences, burnout, illness, and high turnover rates.

Firefighters, specifically, are exposed to significant trauma at work, and are generally not taught skills that will help them protect their mental health, according to the Canadian Association of Mental Health, which contributes to higher frequency of mental illness and a rate of suicide among firefighters that is 30-per-cent higher than the general population.

Recently, a BC Wildfire Service firefighter who used to live in Whistler reached out to discuss his experience of being injured while in the line of duty—and the lack of support he said he felt from his employer.

Pique has agreed to withhold the firefighter’s real name so he can discuss the matter freely, after he signed a non-disclosure agreement with the provincial government.

Hurt on the job

For over a decade, John spent every season fighting fires. It was challenging work that brought him to nearly every corner of the province—and he loved every bit of it.

John worked on initial attack crews in Hope down to the stunning peaks of the Purcell Mountains in the Kootenays. John saw it all, but his life changed one unfortunate day.

John and a motley crew of firefighters were dispatched to fight a small but rapidly growing fire on a mountainside near Kootenay Lake in late August 2018.

Then, disaster struck.

“At the end of a long day, I was walking alone on top of a ridge, and the ground gave out underneath me,” John explains.

“My 30-pound backpack was still strapped on my back, and I had my chainsaw in one hand. I started tumbling like a tomahawk, with the weight of the pack [pulling me down], and eventually, I stopped by smashing my head against a tree.”

Battered and bruised, John sat for a few minutes, trying to get his bearings. He knew right away he had suffered a concussion. Still conscious but in shock, John made his way back up the hill to his crew, vomiting a few times along the way.

At that point, John didn’t know the full extent of his injuries—but he knew they were bad. “When I got back to base, my right knee was the size of a grapefruit, and you could see it through my pants,” he remembers.

John agreed to stay on the job and assist on the radio, while taking it easy on his injuries, a decision he now regrets, noting he should have sought hospital attention immediately.

“I felt like an idiot because I’m so passionate about my job. I returned to help and agreed with one of my officers and crew leader that I would remain on duty and assist the two firefighters on the radio,” he says.

“I would stay in my hammock, with ice packs that we put into the creek, and take care of myself for the last three days of that fire while people were taking days off.”

Two days after his injury, John finally made it to a local emergency room, and it didn’t take long before the doctor signed the appropriate papers to send him home from the job. Once back home, his long battle with mental health would truly begin.

John spent years working through rehabilitation along with a long, complex worker compensation claim process that brought its own toll on him mentally as he struggled to get each of his injuries recognized.

After two years of battles between the BC General Employees’ Union (BCGEU), the union representing wildfire fighters, and B.C.’s Workers’ Compensation Board (WCB), John’s case proceeded to a worker’s compensation tribunal that ultimately resulted in him winning the case, getting recognition for the damage to his knee and mental-health issues.

His mental health had declined substantially during rehabilitation and the long WCB claim process. “I developed severe depression and anxiety from all that and losing my job and everything I loved doing,” John says.

Following the workplace accident, John says he struggled finding suitable work and now relies on disability payments to survive. Initially, he had a chance to re-train as a truck driver, but his concussion symptoms prevented him from taking on the new opportunity.

“That’s when I reached my mental limit. I reached the bottom, and if I went down with that, I would have ended up doing something stupid.” John says. “I can’t work more than two days a week in a noisy environment. So the rest of the time, I’m at home and try to do as best as I can.”

“My mental health took a big hit over the last four years,” John adds. “From working and being passionate about a job and then when something goes wrong, realizing that no one is there for you, except for the union.”

While John continues to deal with the pain from his workplace accident, he is still at it, working as a carver and leatherworker, one of his hobbies before the injury.

John’s story is just one of many, as first responders in British Columbia continue to deal with mental health injuries at an alarming rate.

The brutal statistics

Statistically, first responders are much more likely to all deal with depression, acute stress disorder, operational stress injuries and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

According to the Centre for Suicide Prevention, first responders are two times as likely to experience PTSD compared to the general population, with paramedics having the highest estimated level of PTSD of any profession, at 22 per cent.

The number of mental-disorder claims from first responders is on the rise as well. According to WorkSafeBC, between 2019 to 2021, there were 1,705 accepted mental-disorder claims across all eligible occupations. Broken down further, paramedics topped that list, at 521 successful claims between 2019 and 2021; followed by nurses (443); correctional officers (276); firefighters (170); emergency response dispatchers (127); health-care assistants (80); and police (88).

In 2021, 6,352 mental disorder claims were made province-wide across all sectors, with 2,325 accepted.

Over the past several years, the provincial government has amended the Workers Compensation Act to make another additional eight professions—including firefighters, correctional officers, paramedics, police officers, healthcare assistants and nurses—eligible for presumptive mental-disorder claims. The changes mean that presumptive illnesses under the Workers Compensation Act can be recognized as being caused by the nature of the work, rather than having to be proven to be job-related in order for employees to access supports.

Fighting back

Tackling the mental-health struggles inherent to these frontline professions is a difficult task.

According to Fire Chiefs’ Association of BC president Dan Derby, the fire service is “doing a lot of work to create mental-health resiliency to help firefighters understand the unique psychological challenges facing firefighters in our province,” he says.

“We hope this will reduce the shame and stigma of psychological challenges facing our firefighters.”

Dr. David Kuhl is one such person helping first responders mitigate the on-the-job impacts to mental health. A professor in the Departments of Family Practice and Urologic Sciences at the University of British Columbia, Kuhl primarily focuses on men’s mental health and has worked closely with veterans, first responders, and men with cancer. Along with fellow doctors John Izzo and Duncan Shields, he is also the co-founder of Blueprint, a non-profit aimed at improving men’s well-being and enhancing their positive contributions to their communities.

Blueprint has worked with B.C. first responders to create resiliency programs, such as the BC First Responder Resiliency Program, designed to help people deal with mental health and develop blueprints to move forward with their traumatic experiences.

“Basically, what we’re looking at is to enhance the integrity and well-being of men for the value of families, community and the globe,” Kuhl says.

Kuhl got involved in the project because he recognized working collectively with first responders in greater numbers would have a more significant impact than he could achieve on a patient-to-patient basis.

“Our goal is to equip first responders to diminish the possibility of trauma and direct them toward appropriate interventions if they’ve experienced trauma,” he explains.

The program offers a four-day retreat held at Loon Lake, near Maple Ridge, where firefighters dealing with mental health issues can come together to work through their trauma.

Developed through firsthand interviews with firefighters about their own challenges with mental health, the program has been adapted over the years in an iterative process until it had the desired outcomes, both clinically and statistically.

“We haven’t done a qualitative study about the impact of this program, but word of mouth is getting back to us now about how much it’s changed the lives of individuals, their families,” Kulh says.

“They will say it’s also contributed to changing the culture within the fire halls and fire departments, and those haven’t been measured,” he adds.

Kuhl believes the number of mental-health claims in B.C. has increased recently because the WCB has made claims more accessible—but there still needs to be more supports available for first responders at the ground level.

“I think the compensation board has done amazing things in the last year to make intervention and treatment available for people,” Kulh says. “I think part of the reason the numbers have gone up is because they’ve re-examined what the criteria necessary for people to qualify are, so they’ve greatly improved their response to the need.”

“Yet it’s not enough from my point of view. Every municipality and city should have a budget item for intervention and prevention to provide the care that first responders need.”

An uphill battle

According to Bob Parkinson, director of health and wellness for the Ambulance Paramedics and Emergency Dispatchers of BC, more organisations must invest in ongoing mental health programs instead of the current Band-Aid solution.

“I think we have to do more; everything you and I are talking about right now is [post-care]. So we’re already injured and trying to pick up the pieces,” Parkinson says.

“We have to get ahead of this; there has to be better training. I heard this from a military mom who lost her son. And her statement was, ‘We have to put as much money and effort into helping these people as we do into training them to do their job,’ and I agree.”

Parkinson believes there needs to be more education upfront so that people understand the potential impacts waiting for them on the job, as well as the resources available to them.

Waiting for support until a first responder’s mental health has become a concern is already too late, says Parkinson, arguing for a more proactive approach.

“We have to put a lot of effort into keeping them safe, and I think we’re starting to do more, but we have to go beyond that,” he asks.

“How do we help them when they’re injured? The discussion is, how do we keep them from being injured if possible, and how do we get them the needed resources?”

“We still don’t have enough clinical support or psychoeducation to help our first responder community.”

According to Parkinson, roughly 30 per cent of the B.C. paramedics and dispatchers the union represents are seeking assistance with mental health, resulting in hundreds of instances of time-loss.

The mental-health stress on paramedics is compounded by an ongoing staff shortage across much of the province, exacerbating the length of shifts and increasing burnout among staff.

Parkinson believes the provincial mental health benefit paid to paramedics needs to increase as well. Currently, paramedics are eligible for up to $100 a year in reimbursements for psychological services, lower than their counterparts in police and fire services, and not near enough to stem the tide of on-the-job challenges.

“Right now, our resources are so low,” he says. “Paramedics get $100 in mental health benefits in the extended program. That’s 20 years old, antiquated, and doesn’t meet anybody’s needs.”

A changing culture

According to Steve Lemon, superintendent of safety and well-being at the BC Wildfire Service, with the fire season stretching longer each year due, primarily, to the effects of climate change, firefighters’ mental health concerns are being exacerbated along with it.

“It’s certainly something we have become more conscious of following 2017-2018, two historically large fire seasons back to back. Certainly, we acknowledge that many of our staff were suffering and struggling,” Lemon relays.

“We clearly saw that people were struggling to return to what would be considered normal for them. So we’ve implemented a number of programs to try to support staff, but certainly, we’re seeing that fires are more complex.”

“They’re more difficult or more likely to be working in and around communities,” he adds. “And certainly, 2021 emphasized all of this. All of the fires that we had in 2021, many of which were very serious. We’re directly involved in communities, which elevates the stress and pressure on our staff.”

With a drawn-out fire season and disasters like last year’s atmospheric river floods placing added demands on the BC Wildfire Service, personnel now typically have less recovery time after being out in the field, another factor contributing to heightened attrition and burnout levels within the force.

“The other element that we’re seeing very clearly, possibly due to climate change, is that the fire seasons are just longer, so there’s less time to recover,” Lemon says.

“The expectations on the firefighters are expanding as the seasons get longer, and then as an organization, we’re going down the road of what we’re calling ‘365 response.’”

During the 2021 season—the most extensive and damaging fire season in the province’s modern history—the loss of time over mental health overtook the number of days off from traditional injuries, Lemon says.

“Mental health is one of the leading causes of time-loss injury. So it’s outstripping slips, trips and falls. It’s outstripping strains and sprains. Which is fascinating to see,” he notes.

Fighting wildfires so close to—or in—the communities where some firefighters actually reside added another layer of stress for firefighters, especially when they had to evacuate friends and family.

“Some of our staff were directly involved when Lytton was burning. The fire department left, and our staff were there trying to evacuate people and were really struggling because of it,” Lemon says.

“That’s a very hard thing to do. They were attached to the community and saw their friends’ and families’ homes burn. Honestly, it had a big impact on them.”

Since John experienced his accident, mental-health resources within the BC Wildfire Service have expanded, including additional staff specifically added to assist with the issue and a telephone counselling service for firefighters and their families to use.

“That’s been a real game-changer so that there’s a clear line [through which] you can talk to a counsellor that is contracted within our organization,” Lemon says.

Additionally, the service is working with the Canadian Mental Health Association to deliver a program called Resilient Minds, designed to help firefighters build psychological strength and a peer support network.

For Lemon, tackling mental health at the BC Wildfire Service is as urgent as ever, as he knows six wildfire fighters over his career who took their own lives—including a suicide that happened earlier this year.

Still, he believes the culture within firefighting is changing, and people are more open to talking about mental health.

“The culture has changed. Everyone is more conscious and aware of mental-health issues. I’ve been in the fire service for almost 30 years, and the transition has been really evident, and a lot of that has happened in just the last three or four years,” he says.

“It very much used to be that sort of suck-it-up, keep-working [culture]. ‘Don’t talk about your problems. Just be quiet and keep working.’ And culturally, that’s changed outside and inside our organization.”

- With files from Harrison Brooks