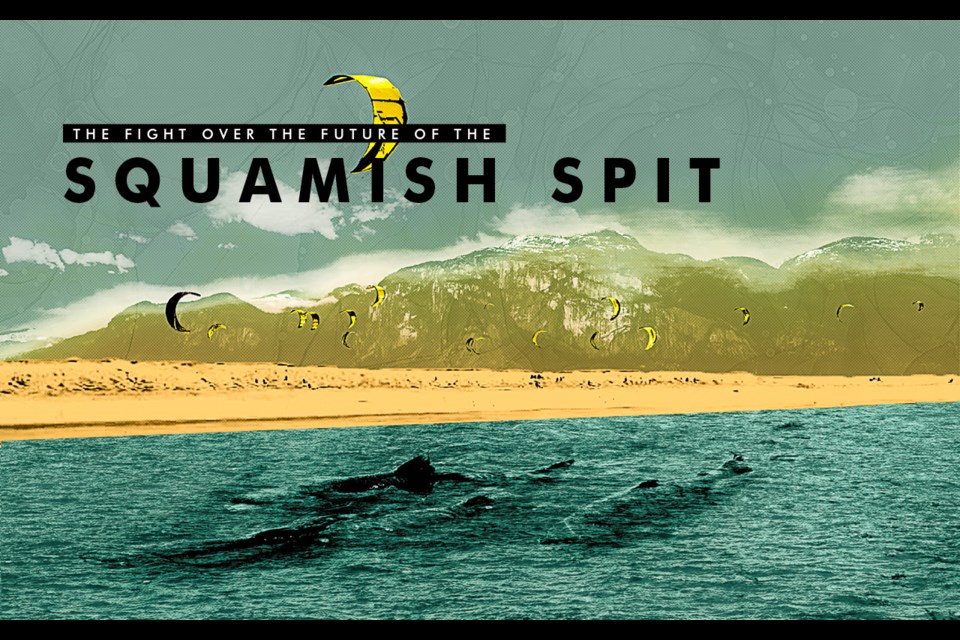

Though the pending dismantling of Squamish’s human-made spit, a Sea to Sky hub for watersports, is contentious, all parties agree that the ocean is precious and salmon are a vital part of its ecosystem.

Most seem to agree, too, that to allow better fish passage, something has to be done to the training berm, or Spit—which was built in the 1970s for industry.

But when and how that is done is where the differences lie.

The Chief talked to some of those who support the project and some who are opposed to the current plan to lay out the issues.

Why and when?

The Squamish River Watershed Society (SRWS), in partnership with Squamish Nation and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), secured funding in 2017 for the Central Estuary Restoration Project (CERP), which is the formal name of the operation that aims to dismantle the Spit.

This project is the latest in a long line of projects by the society over the last 20 years that aim to improve overall estuary health.

The society says the goal of all the work has been to restore fish habitat, tidal connectivity, and overall estuary function after it was disturbed for industrial purposes decades ago.

Some of the examples of previous work, which are outlined in an Ocean Watch Howe Sound report, include improving tidal channels, installing culverts, planting aquatic and terrestrial vegetation, and creating wildlife habitat for aquatic and terrestrial species.

From 1999 to 2013, according to the report by Oceanwise, 15 hectares of brownfield area at the south end of the training berm were restored and culverts were placed along a three-kilometre section of training dike road.

In 2015, SRWS restored part of the estuary that had been an old log sort.

The Spit impedes at-risk juvenile chinook from entering the estuary and funnels them out into the ocean prematurely, causing them to die, say conservationists.

Conservationists claim the number of chinook fell dramatically right after the Spit was installed.

The culverts that have been put in over the years don’t provide the fish passage needed, says Edith Tobe, executive director of the SRWS during a recent tour of the area.

Work may start in October

The dismantling of 300 metres of the Spit—leaving the launching island in place—will happen in stages, likely beginning this fall.

The full 600 m will be dismantled by the end of next year.

The project has to undergo an approval process through Transport Canada and Section 11 of the Water Sustainability Act that includes a public comment period.

The navigational process is to show that the project won’t impact the piloting of ships to the Squamish Terminals.

“Those are very important approval processes we have to go through that we initiated back in April and it takes [a while] as we have to get information to them,” Tobe says.

Public commenting is meant to address any navigational issues, and is not aimed at collecting public opinion on the project as a whole.

If all goes according to plan, in October, work will begin to remove the 300 m worth of the man-made Spit. Eventually, there will be a cut-off at the yellow gate that serves as entrance to the Spit. Tobe says she envisions public access at that location.

During the winter, work will stop and monitoring will continue.

“This was never designed for the current use,” Tobe says of the Spit, referring to its use for recreation.

The increased use over the years is impacting the sensitive biodiversity of the estuary. With the new plan, the idea is to make more managed spaces for people to go to that will keep them away from the most at-risk areas of the estuary.

Alternatives to decommissioning were considered, Tobe says.

A bridge was considered near the culverts, but it was prohibitively expensive.

“It made no sense to put in a $2-million bridge on a structure that is going to erode away around it,” she adds, noting erosion that is already happening at several places on the berm.

More culverts were put in in 2019 and last year. They did bring a vast amount of water down through the central channel.

“But the big thing is, the combined efforts of the culverts alone serve a purpose; removing of the Spit serves a purpose … This really will help bring those fish from the river back into the estuary and allow them access. So the intention was always Phase 1 was the culverts; Phase 2 was removing the Spit.”

Tobe says plenty of investigation and monitoring has, and is, being done.

The project is funded through the federal Coastal Restoration Fund, BC Hydro’s Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, and Pacific Salmon Foundation, and falls under the national Ocean Protection Plan initiative to restore coastal aquatic habitats.

“I am a habitat biologist ... We want to bring this whole area back to resilience,” Tobe says. “When you remove the structure, you allow the estuary to function as the lungs it is meant to be.

“During a flood, instead of the water shooting out into Howe Sound ... suddenly this area is a giant, massive sponge and all that energy just slows the water down.

“This is where not just the fish, but all the birds ... all this stuff is where all these little critters, the invertebrates, live in the mud and that is what the birds and fish are feeding off of. So, by removing this, we are opening the estuary up and providing a massive nursery zone for the juveniles and a massive area for all of those little critters that are the very bottom of the food chain that all of the higher species feed off of—whether it is the fish or the birds or the seals or all the other mammals and moving up the chain to the bald eagles, the bears and to ourselves.”

The Spit has limited the estuary’s ability to do its job properly, she says, adding that reconciliation with the Squamish Nation is also an important part of the dismantling of the Spit.

“They were never consulted about any of this going in,” she says. “They have been engaged at every stage of our restoration efforts. It has all been driven by restoring connectivity between the river and the estuary, for fish.”

The Squamish Nation’s perspective

“In recognition of the harmful effects this physical barrier has on fish movement, particularly movement of chinook salmon into Skwelwil ‘em (Squamish Estuary), the Squamish Nation is in full support of the partial or full removal of the split proposed in this project,” writes Squamish Nation spokesperson Coun. Syeta’xtn (Chris) Lewis in a statement.

“The council also supports the Nation participating in and leading conversations with project partners and stakeholders for this project as adjustments to the Spit are designed in detail, for the short-term and conceptually for the long-term.”

“We have an inherent responsibility to take care of the sts’u’kwi7 (salmon). We have our input and guidance to our partners Squamish River Watershed Society and Fisheries and Oceans Canada on this project, along with many other important habitat restoration projects in the unceded homelands of the Squamish Nation.”

For the love of the wind

Of those who spoke to The Chief, the majority of people who were critical of the plan—including those not quoted in the story—said they also care about the environment, including salmon. As people who use and love the area, they too want to see it healthy.

They want a win-win for both the environment and other users of the area and feel that this isn’t happening currently.

However, they are also asking for their sentiments on the Spit to be considered in the conversation.

Professional kiter Jack Rieder, 21, first learned about the Spit when he was sailing in Squamish as a young teen.

“I learned to kiteboard when I was 14 years old, and when I was that age, there were a lot of people who I now still know, who were probably in their late 20s at the time, and the Spit was basically the mentorship for my entire life,” he says. “All the people that I met there were really respectful adults that helped me grow into the person that I have become. It has been a place of community for me for my entire life since that point.”

Reider is at the Spit almost daily—he works there and kites on his days off.

“Now, I owe my entire lifestyle to the fact that we have the Spit here in Squamish,” he says. “I get to travel all winter and ride for a [kite] company and also work for the Spit in the summer, so my entire life has been shaped by the Spit.”

Reider worries that the younger generation won’t have the same chance he did to build community when the Spit is dismantled.

“The important thing is, the kiteboarding community is more than just about us having access to get on the water every day ... It is the social aspect of community,” he explains. “There are 1,000 members of this [kiteboarding] community and we see them every single time we go out there in the evening. It is a meeting point that wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for that road.”

If the Spit is dismantled, Reider guesses he will still find a way to kite on Howe Sound—but it won’t be the same.

“If you can’t have that easy access to a spot, it makes it almost impossible to train or even just see your friends [there] for the evening,” he says.

“The sad part of it is knowing how much it has affected my life and how my entire life would not exist in its current form if it weren’t for the Spit and the community that I got to be a part of there. And it is super sad that there are a lot of kids that aren’t going to get that opportunity because of the removal. I just can’t even put into words how important the Spit has been to my life.”

Nikki Layton, president of the Squamish Windsports Society, says the plan to dismantle the Spit affects more than just kiters.

“This is actually a community issue,” she says, adding that oceanfront access is being lost with the Spit removal.

“We have measured the kind of safe, swimmable areas the community has to access the ocean and there is only about 260 metres that [is] safe and swimmable and 50 per cent of that is at the Spit and the other part is at the new oceanfront. It is pretty interesting to have a Sea to Sky community with no access to the sea.”

Layton argues the removal of the Spit will have a big impact on the local tourism economy as well.

(The Chief reached out to Tourism Squamish and the Squamish Chamber of Commerce, but did not hear back by press time. )

Economic impact?

Charlie Tindall, of Squamish Watersports, says there are huge questions around what the decommissioning of the Spit will mean for the business he has worked at for a decade.

He said the goal of the kiteboarding lessons the company provides—seeing up to 80 out-of-town clients a day on an average weekend—is to get students to be able to kite from the Spit.

“Our clients, their end goal is to use the Spit, to kiteboard there and be part of this amazing community of people we have here. With that taken away it becomes, ‘Where am I actually going to kite now?’”

Squamish is one of the few places Lower Mainland folks can kite in the summer, he adds.

“We don’t really have any idea how it is going to impact our business at all. We are definitely scared,” Tindall says, adding he moved to Squamish for the access to kiting.

“I have made it into a full-time career. I don’t just teach kiteboarding. I manage the store; I manage the 16 staff we have here who are also here for kiteboarding,” he notes. “If it does go, there is really no knowledge of what is going to happen to our business.”

His family is also buying a house in town and worry for their personal finances, Tindall admits.

He also says that he doesn’t understand how the issue became kiter-against-fish, when all the kiters he knows, especially locals, absolutely do care about the environment and salmon.

“I really don’t know where that came from. When I first came here, the people that I know who are kiteboarders and involved in kiting, were all like fishing guides and backcountry guides and biological engineers and chemical engineers, doctors and stuff … These are upstanding members of the community who are conscious, intelligent people who kiteboard and they definitely care. I care,” he says.

Tindall would like to see more clarity around the issue—especially coming from the municipality—so folks know what is going to happen and can plan accordingly.

What about Nexen beach?

While the new Oceanfront Squamish park (renamed Sp’akw’us Feather Park) on the old Nexen Lands—which isn’t built yet—will likely be “wonderful,” says Layton, it is going to be very busy with all the activities being accommodated there.

Consider, she says, all the user groups that are planning to access the new park including families, paddleboarders, boaters, jet-skiers, members of the sailing centre, windsports enthusiasts and eventually floatplanes.

“The potential for conflict and injury is huge,” Layton says.

The Society has been left to figure out some sort of ferry service to the island, which will be the southernmost tip of the Spit that is set to remain.

“We are a not-for-profit organization whose mandate from when we started in the late 1980s … was to maintain access to a safe area. To become an organization that is running a ferry service is a very different type of business,” she says, noting they would have to get licenses from Transport Canada to operate.

“You have to run a boat; you have to get liability insurance,” adds Layton. “You have to hire a different type of staff and we are already just breaking even with the number of members we have each year. How many of those members are going to decide that it is no longer viable to come out there because they are going to be dependent on ferry service and they have 45 minutes at lunch to get a kite in?”

Layton is also concerned about how this could impact first responders locally considering the Society does 600 retrievals a year.

“Those people are going to wash up on the terminals, those people are going to wash up on the estuary, those people are going to get into conflict with the boats coming in. Those are going to be marine [Search and Rescue] calls, those are going to be Coast Guard calls, and somebody is going to die,” Layton says.

She says the society’s staff has saved the lives of people and if they have to fold, it could add to the risk level.

“If we are not able to stay financially viable as an organization, we will have to shut down and people will keep kiting because the wind is not going anywhere,” says Layton. “They will do crazy things to go out there.”

She also questions the speed at which things have happened with the project and some of the science.

The berm isn’t being taken all the way down to the ocean floor, says Layton, and that could mean fish may not be able to pass through at all times, making her wonder what the whole point is.

However, Tobe says that the way it is planned, other than a few hours a year, fish will be able to easily pass and that the misunderstanding relates to how estuaries work, the tides and how fish pass through—currently that is not the case.

Says Layton: “Of course there are conflicting priorities, and, as the Windsports [Society], we are passionate about the ocean.

“We are not saying, ‘Oh my God, we don’t want this to happen and we don’t care about the ocean and the salmon and everything else.’ We are like, ‘What needs to happen so that the salmon can have a good outcome and how can we find a solution?’ We live in a world where humans and nature have to work together so how do we figure that out?”

The Windsports Society has previously said the plan it understood from the beginning of the project was that the Spit would be realigned. That was in the original plan, when the $1.6 million in federal funds was secured, but the CERP team informed the Windsports group about a year and a half ago, according to Layton, that it wasn’t feasible given the restoration needed to the estuary.

Layton points to other places in the world where kiteboarding, the environment and other interests coexist, including the UNESCO-designated Biosphere in Ireland.

The Windsports Society has come up with what they say is a viable option in a campaign: realignnotremove.ca.

Working with Indigenous artist Xwalacktun, they have designed a realigned Spit that would be a park for windsports and other recreational users of the public, “To make another tourism landmark for this community,” says Layton, adding there has been early support for the idea.

“If it is just money that is the issue, we are confident that if we have partners—the District, the province, the Nation—then we are confident we can raise the money. But we are [a] non-profit organization. We just can’t randomly go build something out there,” says Layton, adding the caveat that the Society can’t take responsibility for the structure once it is built.

“It can’t be the Squamish Windsports society,” she says. “It has to be the District; it needs to be the province.”

What’s the role of the DOS?

Chris Wyckham, director of engineering at the District, says that the District of Squamish has a relatively minor role in the project itself, which he notes may be a surprise to some people.

And he says the District has no intention of project management or building a structure.

“This is a federally-funded project,” he says. “It is a federal project on provincial lands. The Skwelwil’em Squamish Estuary Wildlife Management Area (WMA) is managed by the province. The road is not within the WMA … and the District does maintenance on the road through an agreement with the province. But that is Crown land.”

The District leases the land of the Spit and sublets it to the Windsports Society.

“We plan on continuing to lease it out to Windsports as long as they want it,” says Wyckham. “We have a multi-year lease with them and that will continue to be valued if they want to take boats out there or build some sort of structure. However they get out there, they would have a lease from us.”

Where the District does have a role is in bringing people together. With Squamish Nation, they are facilitating a Squamish Community Vision Committee to look at next steps after the project is complete.

“Squamish Nation and District of Squamish volunteered to co-facilitate a venue where people could talk about what is next,” he says, noting that the two bodies are just facilitating the discussions and donating staff time to do so. “We have a very limited scope in that our role is to bring parties together and talk about very preliminary designs. For example, the first step is how are they going to get boats back and forth.”

The second step is figuring out a medium- to long-term solution that isn’t a boat.

“We looked at who the most highly impacted stakeholders were, and those were the Squamish Terminals, Windsports and Tourism Squamish, and we invited them to come represent the interests that were being most heavily impacted,” Wyckham says, noting others are impacted, but these groups were the most impacted.

So far there have been two meetings of these representatives.

The next meeting in a few weeks will add in various government agencies and the CERP team to try and come up with some things that will work for everyone.

Kim Stegeman, speaking on behalf of Squamish Terminals, calls for all stakeholders to be patient, as needed approval processes for the Spit decommissioning are completed.

“[Squamish Terminals] understands all stakeholder positions and would like to find the solution that balances interests, but only with the correct information, which can only be provided with the technical studies in place so we urge people to be patient and wait for that,” says Stegeman, adding that studies won’t be in until early October.

In the meantime, the port has its own maintenance dredge project moving forward in the fall, with specific details to be shared as part of its community outreach process.

Stegeman notes the Spit was built to support port development in general in Squamish, including a coal port and Squamish Terminals, “which has supported the waterfront industry and the jobs and economic contributions that go along with it for half a century.”

Other projects like this?

In Washington state and elsewhere, work has been underway to remove historic barriers such as dams that impede fish movement.

Though not associated with the Spit project, conservation biologist Misty MacDuffee, who is also a wild salmon program director with the Raincoast Conservation Foundation, has been a part of a similar initiative for chinook in the Fraser Estuary.

There, long jetties that were built 100 years ago to aid ship navigation have alienated juvenile chinook from reaching their habitat on the Sturgeon Bank.

They also stopped the historical flow of sediment, nutrients, other fish, and the natural mixing of fresh and saltwater, she says.

The project needed support from the nearby port, as well as many other agencies, in order to begin dismantling parts of the jetty, which happened two years ago.

That project also needed navigational studies, as the Spit project does.

There is not the recreational interest in the area as Squamish has, however, she acknowledged.

MacDuffee says she is also familiar with the project set for the Spit. “Individual chinook will spend two months and even up to three months rearing in the estuary and when they don’t have proper access and its ability to support them is inhibited, restricted and degraded, that has an impact on juvenile salmon that really require that rearing environment.”

MacDuffee says that even if the berms are just one factor in the decline of fish, they are one that can be mitigated.

“When we have opportunities to actually change something that we know is having an impact, it is the logical thing to do,” she says. “We know how much rearing habitat in the Fraser has been lost and we know that this is going to increase the available habitat for these fish. It is not the only limiting factor, but the more that we can give them habitat and restore the habitat that they are using, the better chance of them tackling these other issues. It doesn’t mean they don’t need to be tackled, but we have to give these fish the best chance of survival and habitat is such a fundamental piece of that, that is sort of the most obvious thing you want to address.

“To remove that section of the Spit, it is going to change the estuary so much. That estuary has been so impacted ... [These jetties] have these impacts on function and being able to restore function is such a valuable thing.”

Next, MacDuffee and her team are working to tackle three other jetties in the area to increase fish flow.

A version of this story was originally published in The Squamish Chief on Aug. 13. Read it at squamishchief.com