I first met Thomasina Pidgeon about this time last year. I was making a photo essay for The Tyee that looked at a new camping bylaw the Squamish District had proposed, which would put an end to the community of residents living inside their vehicles—residents like Thomasina Pidgeon.

As I was about to drive home, Pigeon asked if I wanted to go on a walking tour of downtown Squamish so she could show me places that were soon to be developed. I accepted. Her knowledge of the various building lots and their history was striking. As I photographed them, she sheepishly told me she’d been awarded a grant from Squamish Arts Council to exhibit thousands of photographs she’s been taking over a 20-year period, documenting the growth and gentrification of Squamish.

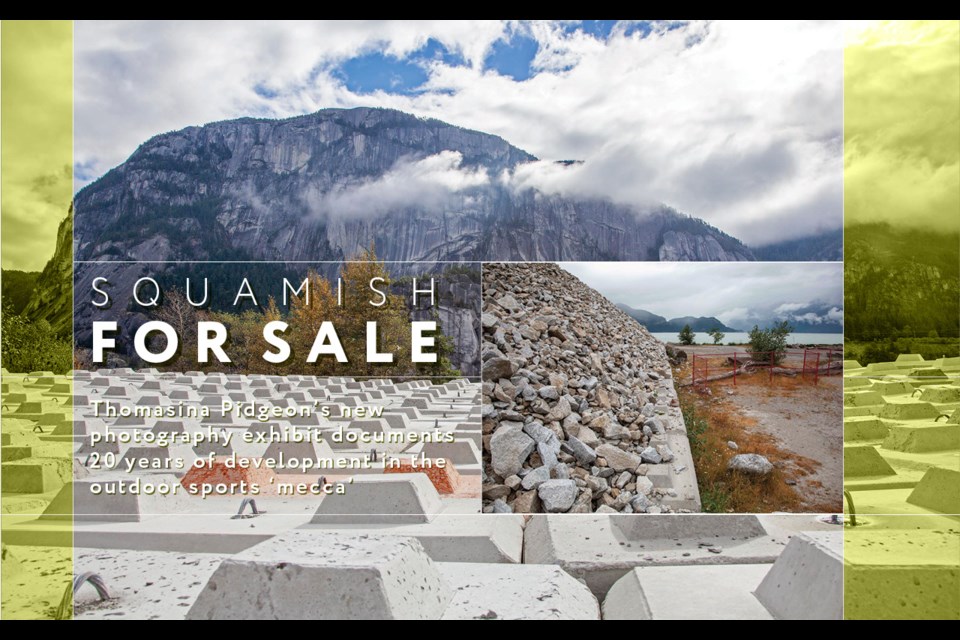

It’s no secret that Squamish has seen an abundance of development since the 2010 Olympics, placing it on the map as Canada’s recreation capital. Tourism Squamish dubs itself a “mecca” for rock climbing, hiking, mountain biking and windsports, and with its picturesque Howe Sound setting and 360-degree granite mountain views, it’s no real surprise that increasing numbers of younger Canadian residents are yearning to relocate there—and developers are cashing in.

When we thought the pandemic might slow demand, the opposite happened. The shift towards remote work gave many city professionals the freedom and opportunity to relocate away from the office and instead prioritise where they like to spend leisure time. As a result, Squamish has experienced record-breaking real estate activity in the housing market in 2021, catching up to places like East Vancouver for apartment sales.

New developments such as Oceanfront, which occupies the undeveloped land surrounding Nexen Beach, is building condos for 6,500 additional residents, and at the current market value, this can only attract a very targeted, affluent crowd.

It’s easy to see why Pidgeon is troubled about the continuing growth and in Squamish, particularly now the District has finally implemented it’s new camping bylaw, which outlaws her lifestyle as a person living inside her vehicle—something Pidgeon’s done for 20 years. This is why I think her story—from her perspective—is important. And as a photographer and visual journalist, I can’t help but be excited by someone trying to spark debate for the purpose of social change through exhibiting photographs. That’s why one year on, I spoke to Thomasina Pidgeon about her project, ‘Changing Squamish’.

Tell me what inspired you to make Changing Squamish?

As a resident of Squamish for over 20 years, I witnessed the landscape and people gentrify at an increasing pace. While I originally set out to capture what was being lost through this process, I understood that these developments were critically related to our environmental crisis. I wanted to create a project that prompts us all to critically engage in conversations around these topics, so we can start to find a solution and create real change.

Changing Squamish speaks to the idea that “sacred views are commodified,” which I find interesting as a photographer. Can you tell me more about this?

The commodification of views is seen when paying top dollar for the best seat at a concert, or—as is the case with Squamish —paying the highest rent or mortgage to have the best condo view of the Stawamus Chief or Howe Sound. This might be great for investors, but it doesn’t mean it’s the best decision for the community.

In downtown Squamish, there has been increasing public pressure to protect the views through smarter building design, such as having higher buildings at the back and the lower stories closer to the Chief. This way we get density and everyone gets to enjoy the view. Unfortunately, this opposition has been largely ignored and the zoning bylaws that restricted building heights to two to three stories for downtown buildings, were amended and increased to six stories and above. This way, the best view goes to whoever can afford it, while the rest of us are left in the shadows to look at the monster-sized condos we can’t afford.

Are you anti-density?

No. Density is great if done with forethought and quality, however, Squamish lacks both. What we have is capitalism working its powers with the objective to make the most dollar in the shortest amount of time.

Real estate is a component of a boom-or-bust economy and because of the intense marketing of Squamish, people have been desperate to move here. Yet within this process, the District has changed with little regard for what the actual community wants, and what once made Squamish attractive, is no longer.

I do find that we’re often lured by council and developers who frequently use words such as “sustainability,” “mutually beneficial” and “contemporary” to gain support for their projects, when in reality they are shaping human behaviour towards high-impact lifestyles, creating environments that encourage driving rather than biking, and failing to include commercial lots for places like grocery stores. Meanwhile, we continue to see low-density, million-dollar home developments such as Crumpit Woods, North Crumpit and Legacy Ridge sprawl into our forests, along with the many single-family attached row homes. That’s not density—it’s urban sprawl for the affluent.

What was Squamish like when you moved here in 2000?

In 2000, Squamish was a quiet town where the loggers outnumbered the climbers and we could sleep under the stars without complaint. It was more free, slower, and relaxed. There were more characters walking around, less dogs, more space. Mind you, some businesses weren’t thriving like now, but the cost of living was more balanced. People didn’t have to work two to three jobs just to afford rent or pay their mortgage.

As a long-time vehicle resident, how has your connection to Squamish changed over the years?

I definitely feel at a loss. Much of what attracted me to Squamish is gone. People honk if you don’t immediately put the pedal to the metal when the lights change. There are more big-box stores, fancy and expensive boutiques. The places I once went for solitude are busier and driving further doesn’t make a difference. Familiar areas have been torn down and the view of the Chief is being replaced by condos. We have more outside investors than ever before.

An old friend who once lived here recently came back and mentioned to someone that he felt like he didn’t belong here anymore, to which this person responded, “Yeah, you probably don’t.” Both these remarks are heartbreaking to me.

You’ve been a leading voice in the activism surrounding vehicle living policies and the camping bylaw in Squamish. Do you think activism has made a difference?

Yes and no. We have managed to stave off the bylaws for a couple of years, but in the end, all the progressive solutions we put forward were ignored, and the meetings we had with the Squamish District felt like consultation for the sake of consultation.

The no-camping bylaw was finally adopted this May. We are now, not only still stigmatized as being freeloading tax evaders, we are officially outlaws for sleeping in our vehicles.

What are you first: a photographer or an activist?

Not sure! I remember feeling them both as a child.

Your life and work takes many forms. You’ve broken several records as a professional climber and are now studying political science. How do these disciplines feed into ‘Changing Squamish’?

Climbing and academics requires you pay attention, ask questions and be determined in the face of adversity. Climbing specifically requires the sacrificing of pleasures, thinking outside the box and being willing to change. If something doesn’t work, we don’t keep trying the same method—we change until we find a solution.

Political science has given me a much deeper understanding of the forces around me and taught me to question and think critically about absolutely everything. What’s happening in Squamish, from the gentrification to the camping ban—it’s so textbook, it’s almost laughable. By looking at these issues from new perspectives, maybe we can find real solutions that address the root cause of the problems, rather than continue on as we have.

Did you always plan to exhibit the work?

No, I didn’t always have a plan for this project, but have continued to feel motivated by the unwavering connection I witness between the economic expansion going on in Squamish and other parts of the world in relation to our social, political and ecological crises.

Fortunately, the theme of the 2019 Squamish Arts Council Community Enhancement Grant was “This Place, Our Home.” This resonated perfectly with this project, so I applied and here we are. It’s been a great support and is what made these exhibitions possible.

Who are two artists or people that influenced your project and why?

The work of Dorthea Lange and Leanne Betasmoke Simpson are so inspiring to me because they tell it like it is. There is no taming it down or hiding certain truths to soften the message. They ask us to look honestly at a situation and to think critically about what we see.

But in all honesty, the people that most influenced this project are the folks that I met while out shooting. Everyone I talked to was generally disgusted or saddened by what is happening in and around Squamish. I met two long-time Squamish women who no longer bring their kids to Nexen Beach because it would upset them to see their playground destroyed.

One of the saddest comments came from my Squamish Nation friend Charlene Williams, who said, “In 10 years there are only going to be Indians and millionaires, and we don’t even have enough land for our own people.”

You’ve already exhibited Changing Squamish at the public library and the Green Olive Cafe. Do you have a sense of what the response has been from viewers so far?

There are a few folks who don’t understand or simply don’t agree, but mostly it has been overwhelmingly positive. One woman who recently saw the library exhibit withdrew from the real estate program that she had signed up for—she didn’t want to be part of the problem!

People have commented on how powerful, yet sad it is to see this exposed. Personally, I see this as a success because this is the very point of the work—to get uncomfortable and look at things we don’t want to look at. It’s the only way to start finding solutions. I hope this will inspire more people to stand up for change.

Who are you most hoping will engage with the upcoming exhibitions?

I am hoping to engage everyone—residents of the Lower Mainland, politicians, developers, business owners, visitors and tourists. We all play a crucial part in shaping our world, including influencing government decisions. This is particularly important right now with the [Sept. 20] election.

According to Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist from Harvard University, it only takes 3.5 per cent of the population to make real change. We need to stop being passive citizens.

In Changing Squamish, you urge that “we must re-evaluate our needs and consider this finite and fragile planet on which we live.” Can you tell us a little bit about what re-evaluating our needs might look like?

There is this mentality that is nurtured by capitalist and colonial systems that we must continually grow and progress. To me, progress means building our society around values of inclusivity, diversity and social and environmental justice. It means reorganizing economic activity away from extraction and toward cooperation and caring.

Many vehicle residents use less resources than home dwellers and because they live outside, they have a closer relationship and connection to the land. Even so, they are assumed to be an environmental risk and penalized for not contributing enough, which comes back to this colonial idea that there is only one way of being. How boring our society would be if we all lived the same way!

What’s the solution to all this?

I think we need to question the idea that more of the same—growth and development—is going to solve all our problems. Instead of this sterile monoculture of gentrification, we can design neighbourhoods to be diverse and influence positive lifestyle choices where quality of life is the focus, rather than material wealth. We can protect views, green spaces and create more food security through community gardens and green roofing. Instead of big-box corporate commerce, we can create local economies to shorten supply chains and support local goods and business.

We need responsible, future-thinking interventions that take into account existing residents, natural landscapes, critical view corridors, public space and access. We need to move beyond current standards that merely flirt with the idea of “eco-efficiency”—being less bad doesn’t make it good. And most importantly, we need to include Indigenous voices as part of the solution, whose knowledge and wisdom is essential to our survival.

Changing Squamish is on view at the Green Olive Cafe, the Squamish Adventure Centre from Sept. 9, and at The Ledge Community Coffee House from Sep. 11.

Amy Romer is an award-winning visual journalist based in North Vancouver. Her work focuses primarily on human rights and the environment. She is a National Geographic Explorer.

This photo essay originally appeared in The Tyee on Sept. 10 and is reprinted here with the author’s permission. Find it at thetyee.ca/Culture/2021/09/10/Squamish-For-Sale.