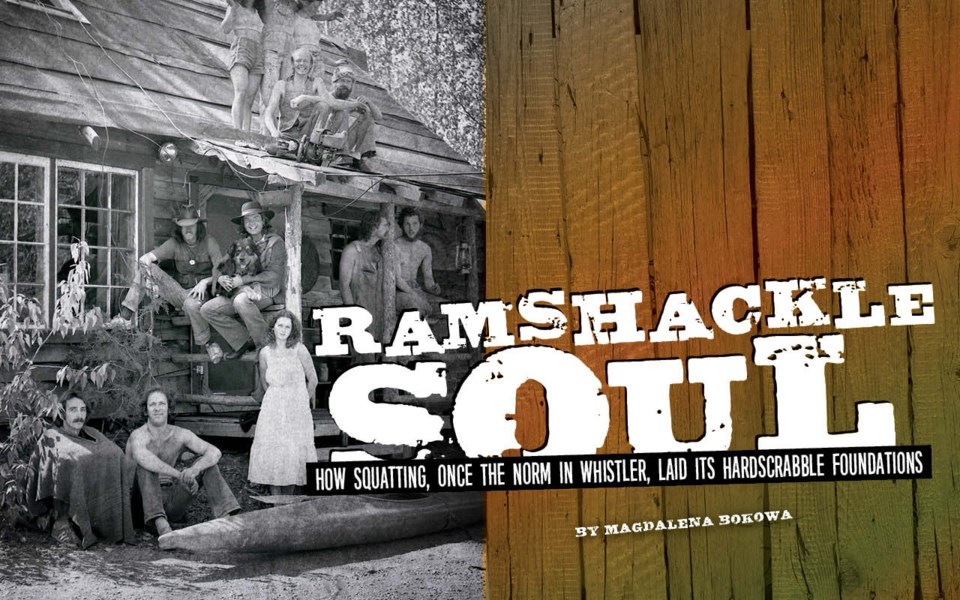

At first glance, you wouldn't think much of the tiny log cabin nestled in the woods. Fastened together with salvaged speckled wood and repurposed windows, flanked by a bountiful vegetable garden, it wasn't quite like the grandiose ski chalets Whistler is now known for—but it hardly felt out of place either.

Smoke from the chimney billowed outside while kerosene lamps illuminated the modest cottage where the bedroom was found sandwiched into the rafters, affectionately known as the loft. A cooler stocked—and sometimes ravaged— by resident critters held only the necessary supplies, while a tape-deck powered by a car battery hummed tunes and revamped any sour moods. The walls teemed with books laid out on homemade shelves, while the sizeable array of house plants were fed by the creek water collected nearby.

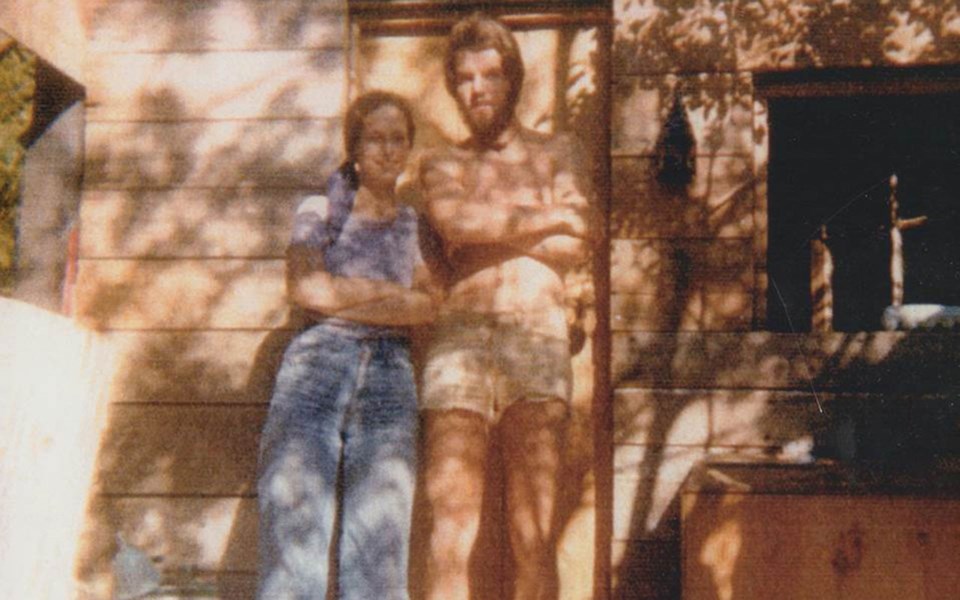

If the inhabitants of this 1975 home were to describe it in one word, they—they being former Whistler Mayor Nancy Wilhelm-Morden and her now-husband, Ted—would say, "Homey. It was very, very homey."

Or, you could also describe it another way.

A squat.

Unwelcome squatters became Whistler's long-term residents

Dig into Whistler's colourful history and you'll find countless stories of adventurous Whisterlites who have come up with creative ways to call the Sea to Sky home since its earliest days. In the mid-'60s, newly named Whistler Mountain began to burgeon; the first lifts had been installed and whispers of a strangely beautiful mountainside full of deep powdered snow emerged, as did those chasing it—in droves.

"It was always really hard to find a place to live," begins Wilhelm-Morden, who arrived, fresh-faced from Ontario, in 1973 and spent four years living rent free in the aforementioned squat cabin built by Ted in the fall of 1975. "In the summer, it was no problem to find housing, but in the winter all the owners came up from the Lower Mainland to ski, so there has always been an issue of supply."

By the early '70s, communities surrounding Alta Lake were experiencing such rapid and haphazard growth that condos outnumbered cabins and were crammed into neighbourhoods such as Creekside. Squatting—the act of occupying land or uninhabited buildings, often times on Crown land—started to become the norm, among other alternatives such as van dwelling or camping.

"There were 600 residents in Whistler at the time. Sixty were squatters. That's 10 per cent of our community," estimates Wilhelm-Morden. "It was a common thing that people were doing ... and the idea was not to spend a lot of time or money on it because you could be evicted and lose it at any moment."

As the rest of Canada was beginning to experiment with the hippie lifestyle, some in Whistler were already doing away with social norms and embracing communal living. In a mountain resort town full of industrious spirits, escaping conformity and embracing community were king. "It was definitely a very hippie thing to do," laughs Wilhelm-Morden. "But it was also just a way to reset and go back to simpler days."

For the four years they lived in the 120-square-foot (11-square-metre) cabin, the pair never had electricity or running water. "We went from urban kids, born and raised in cities, to living quite a different lifestyle. We made so many memories that will be forever etched into my mind," Wilhelm-Morden says. She continued commuting to Capilano University to continue her studies while living in the squat, and the pair would plough a parking spot off the highway and hike the 15 minutes in to their tiny abode. "The car would give you away that someone was there. It wasn't obvious that we were living there, but we also weren't hiding it," she notes.

Wilhelm-Morden, who recently ended her term as Whistler's mayor after 17 years in public service, laments that her only transferable skill at the time was her knack for persevering. "My mother was a big fruit canner so I carried those skills with me, but not much else."

In due time, however, they adapted and learned, hosting frequent dinner parties made with meals cooked on a wood stove. They also had frequent run-ins with pests, namely mice and raccoons and, at times, even bears. "We were living so close to nature. I mean, we were living in nature," she says, laughing as she recalls one particularly resourceful bear that got into the habit of knocking over the cooler they kept in the creek during the summer months, consuming its contents quite regularly. "Let's say we had to modify things quite a few times."

Ramshackle shindigs in the valley

If the squat life sounds almost utopian, it certainly seems outside of the typical, run-of-the-mill experience—and in a town where the former mayor described the male-to-female ratio as "10 to one," most squats were far more rudimentary. Old, abandoned fur-trap cabins, dilapidated logging cabins and old mining shacks were prime squatting material. "It was a pioneer kind of lifestyle, in the spirit of Whistler's earliest pioneers such as Myrtle Philip," says Whistler Museum executive director Brad Nichols, who has researched the history of ski bums and squatters extensively throughout the years.

"People were coming here to build a dream, to ski a beautiful place and they would do whatever they could do to stay here," says Nichols, who is developing an upcoming exhibit that will focus on the history of housing in Whistler.

"Squatting embodied the free spiritedness of the '60s and '70s that Whistler is still known for," he continues. "Someone once said, 'Whistler was built on the smiles of 20 year-olds,' and I think it's one of the best ways to describe it."

In an excerpt from "The Squatters," G.D. Maxwell writes, "(They) bore a striking resemblance to pioneers from a century earlier. Shaggy hair, shaggy beards, unkempt clothes, and those were just the women, mind you. They worked hard in the summers, skied hard as members of the UIC Ski Team during the winter, and partied hard all year long."

The squatting game

If there were homey squats, then there were also party squats, such as the original Toad Hall—yes, that one—before its second incarnation in the Soo Valley, famous for the namesake poster that now adorns walls across Whistler featuring 14 naked men and women, clad in only ski boots, toques, giggles and smiles, standing proudly before their soon-to-be-demolished home. The poster is so legendary in ski-bum circles that it can still be found in rather obscure places, such as in an après ski pub in Kitzbuhel, Austria, where word has it anyone from the photo drinks for free.

The original Toad Hall was a ramshackle building, insulated by sawdust, and first occupied by just four men, one of whom was John Hetherington. Part of a motley crew of self-professed ski bums who often slept on the floor, Hetherington worked ski patrol and lived there for two winters along with a few "lifties who worked the T-Bar." He described it as "the coldest damn place I've ever lived in."

They soon learned to use the wood stove, though it only heated the kitchen, and got a friend to wire a stereo for music and settled into what Hetherington says was a "primitive existence." Though the living conditions were crude, the parties were anything but and a reputation started to quickly build. The owner soon got wind of Toad Hall's rapidly growing reputation and decided to take back the residence, leaving them homeless yet again.

Hetherington recounts that to abate the reputation of the first locale, two old "Toad Hallers" borrowed fancy clothes, pretended to be married and effectively coaxed the owner of the new compound into renting the large parcel to them, with its main building and other outbuildings, for $75 a month. Two quickly became 20, and the legendary Toad Hall 2 was birthed on Green Lake.

The Soo Valley Toad Hall quickly became a scene of wild and rugged debauchery. Hetherington, who wasn't officially a resident at that time, but a frequent visitor, noted more attention was given to the sound system than other domestic niceties. "It was pretty outrageous the stuff that was going on over there ... People would show up from all over the place and bands would come up from Vancouver and play for free for three straight days, so the place got that kind of reputation."

Meanwhile, Hetherington had moved with George Benjamin into another local hippie haunt known as Tokum Corners. Without power or running water, "We had to climb over the snowbanks and over the railroad tracks to bail water from the lake and back again," recalls Hetherington. The place eventually came up for sale, and after a bit of negotiating, Benjamin and Hetherington bought the property outright, with cash.

The price tag? $1,100.

They lived in it for seven years until "the railways took it from us," Hetherington says. During that time, Hetherington says they installed a well, a pumphouse and had not only running water, but hot water. "Everyone thought that was amazing when that happened," he laughs. It was like we were rejoining civilization.

"It was a great place to live," he continues, "The lake was right there, we built a big dock and it was a great place to swim." Asked how the neighbours—sparse at the time—treated the duo and their rotating houseguests, Hetherington acknowledges it was a "love-hate" relationship but that they tried to make amends by "shovelling snow off their rooftops or looking out for their homes when they were gone."

In the same vein, Andy Munster, a long-term resident and local builder, also had a squat, next to Diversion Creek, which would later be known as the first house built on the future site of Whistler Village. It was also known for its annual parties, which Munster described to Maxwell as typically lasting "about three days," and featured, "A big bathtub full of punch—whatever got dumped in—and bands and huge bonfires."

Munster scavenged the local landfill next door for wood and spent his hard earned money on solid roofing materials. He built the squat for a whopping $50. Not having second thoughts of building on Crown land at the time because of its proximity to the town dump and it being a problem area for bears, it quickly became the centre of an inevitable showdown with local authorities.

The heyday is over

As is still the case today in a tight housing market, tensions arose as Whistler kept growing and the first plans to change the town dump into what is now Whistler Village took hold. Residents weary of the all-night parties started to complain. "They choose to live like gypsies while others pay room and board," wrote Ted Franks in a 1978 letter published in the Whistler Question. "They are completely dedicated to their undisciplined lifestyle of enjoying everything the valley has to offer without contributing in any way."

The provincial Land Branch, executors of the Crown land—which the squatters were occupying and which was later sold for the development of the village—perhaps under pressure from the Alta Lake District Ratepayers Association, issued eviction notices to more than 40 squats in late 1977. The squatters fought back, spearheaded by their shaggy-haired spokesperson, Charlie Doyle, founder of the irreverent alternative newspaper, The Whistler Answer, who was squatting in an old trapper's cabin on the Cheakamus River. "It was a lovely place," he said to Maxwell. "I lived there for four years, until 1979."

The group amassed 300 signatures (a feat for a town of only 600) to secure an extra year at the village squats. They argued extra time was needed "to arrange living arrangements due to a severe lack of low-income housing available in Whistler for its seasonal workforce," which still rings true 40 years later.

The powers that be eventually caved and supported the measure, giving the squatters a one-year extension and a $500 bond under the promise to "remove their structures and return the land to its natural state" after the year was up. The Lands Branch was quite serious about the potential evictions, enlisting the fire department to set fire to four illegal squats on Fitzsimmons Creek as a way to drive home the message. The first squat that was destroyed? Andy Munster's.

At the same time, Wilhelm-Morden and her husband recognized the squatting free-for-all was over and decided to be proactive. Thinking they had built their tiny abode on Crown land, they decided to "take the bull by the horns," and told the authorities they were there but were planning on vacating as soon as they finished building their home on a piece of newly purchased land in Alpine Meadows. Instead, they were met with a surly notice from the attorney of the landowner—they had unknowingly been squatting on private land. "Things sped up a bit after that," Wilhelm-Morden conceded.

Then and Now: Silver Linings

No one can dispute that Whistler life has gone from a sleepy ski town to a full-blown global destination. In the same vein that its earlier residents—the ones who are today's small-business owners, realtors, builders, lawyers and mayors—endeavoured creative ways to stay in the ski town, so do the new arrivals of today. Van dwellers remain numerous in the day lots and illegal campsites continue to pop up in the hidden corners of the resort. As first reported in Pique, in September of last year a municipally contracted company removed several truckloads of trash from an illegal campground that was discovered on a small island in Fitzsimmons Creek, near the original Munster. Adrian Moran, co-owner of 50 North Exterior Property Detailing, which cleaned up the site, said it took three trucks about two days to clear roughly 1,000 pounds (454 kilograms) of trash.

"Workers removed everything from clothing to old snowboard boots, food wrappers and tins, a sleeper couch, and at least 2,000 cigarette butts," he told Pique. "One of the things that took us the longest was picking up the cigarette butts. They were just everywhere." Nametags and uniforms were found scattered around the site, just steps from luxury hotels where tourists pay hundreds of dollars a night to stay in peak season.

Those selling lift tickets and pouring drinks in the old squat sites surrounding Whistler Village are still running into the same issues as 40 years ago, except now Whistlerites have to contend with a dwindling housing stock along with skyrocketing price tags.

"When I first moved here nine years ago, you could find a room quite quickly for $600 to $700," notes Mark MacKay, a Scottish transplant who says he is facing eviction with his landlords planning to retire and move back into their investment property. "(Before) it would take about two to three weeks to find a job. Now it's been completely flipped on its head. It takes months to find a room but you can find three jobs in one day."

Lured to Whistler for its outdoorsy lifestyle, MacKay, like many of his friends, says he fears he's been priced out of Whistler and is lining up appointments for house-shares in Squamish. He gripes about the change and although he's thought about leaving, he still thinks Whistler is "very welcoming and all-inclusive." And yet he fears that with Vail Resorts' 2016 takeover of Whistler Blackcomb, the very "soul of Whistler" that the squatters helped pioneer is at stake.

"The way that Whistler is going, it's only catering for the people who have turned up for a season or for a year," says Mackay, commenting on the available staff housing which he says is often expensive, cramped and not conducive to long-term residency. "Those people are only here for one short time, blow a bunch of money, party and then leave. They won't make up the long-term residents or help shape the vision of the future.

"The people, like myself, who are growing their career, well, they can't grow anymore. And it's kind of met with the attitude that the ones that can't afford it, well, who cares? Get out. That you're disposable. It's kind of sad. I feel as though it's just becoming a utopia for the rich."

Finding that balance has left many to question how long they will be able to hold out in Whistler. It may be an exhausting effort but Wilhelm-Morden is hopeful that those wanting to will find a way to stay.

Wilhelm-Morden points to the Mayor's Task Force on Resident Housing that she spearheaded in 2016, which is focused on boosting employee housing inventory, and says various programs offered by the Whistler Community Services Society such as daycare incentives, are aimed at easing the burden many young families are feeling. With Whistlerites spending 44 per cent more on rent and utilities in 2016, the most recent data available, than the B.C. average, it's clear there is still much work to be done.

As a former squatter, Wilhelm-Morden acknowledges it has always been tough to make Whistler home. "But I see Whistler, despite its challenges, continuing to bse a dynamic place," she said. "So if you love living here, persevere, like we did, because it will get better."